More on hidden secrets in Kohat and the mysterious tales it must tell

Two magnificent peaks, locally called ‘Do-saray Ghar’, will catch your sight when glaring at the horizon north of Kohat. The British officers used to refer to these geographical protrusions as ‘The Lady of Kohat’ or ‘Old Woman Nose’, depending on their moods and the effects of the "chota peg" that lifted their spirits in the officers’ mess.

But that is not what I was particularly interested in that day. My friend Shahzad Bangash and I had already spent a few hours walking through the old city of Kohat, trying to explore its rich architecture and heritage. We had obediently followed Professor Iqbal, from the King’s Gate to various mohallahs and streets, and finally emerged out of the walled city from the Tehsil Gate. Throughout this hours-long tour we felt like the children of Hamlin following the Pied Piper.

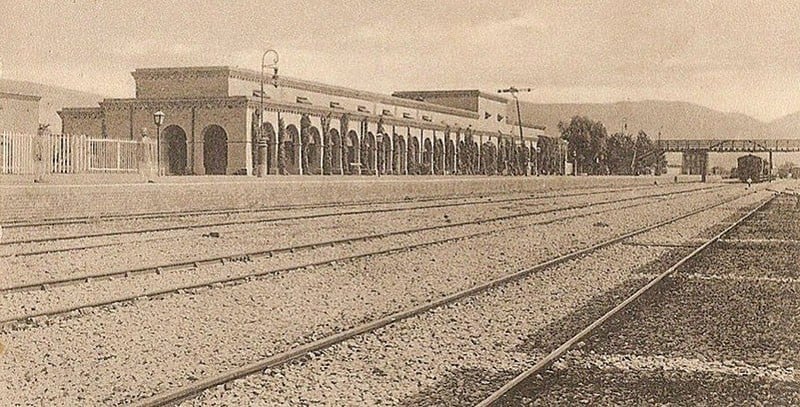

Yet, we missed out a few landmarks of the city, among them were the Company Bagh, the Cantonment Railway Station, Charsi (Hashish) Gate and the British-era fort.

Our weary legs obligated us to drive our vehicles on the Shahpur road towards the famed graveyard.

The historic graveyard is an architectural wonder of brickwork consisting of the 18th century mausoleums of Durranis whose rule was ended by the Sikhs. Most are adorned by Persian verses. But their current state of neglect represents the interest of the Archaeology Department. Conspicuous among the graves is a rectangular structure with a large tapering tower over the front entrance and four small domes on each corner. On entering this elongated room, you find opposing arched passages, windows for cross ventilation and a Victorian fireplace at the far end. It was most likely a place for the royalty to rest while the burials were in progress.

As we drove towards the city we re-crossed an unmanned railway crossing that had attracted my attention earlier but we had decided to explore it on our return. This crossing was on the narrow gauge line which was laid in 1903 as a Great Game strategy to counter the growing Russian menace. While it served the local tribesmen from Kurram to Tirah as the only means linking their mountains with the emporium of Kohat.

In May 1919, the Afghan commander Nadir Khan started the Third Afghan War by crossing the Khurram valley and besieging the small mud fort at Thul manned by Sikh and Gorkha troops. The Thul Relief Force was quickly organised in Peshawar under the command of Brigadier General Rex Dyer, an officer under serious inquiry for opening fire and murdering helpless ‘natives’ at Jallianwala Bagh in Amritsar.

From Kohat’s City Railway Station, Dyer’s troops were swiftly transferred to Togh, a railway village 27 miles short of Thal to launch an aggressive counter-attack on the besieging Afghan troops. Royal Air Force BE2E Biplanes flew some sorties from makeshift airfield at Dakka village near Kohat and helped in instilling terror on Afghans troops.

Dyer known for his qualities to inspire troops lived up to his reputation and soon Nadir Khan was asking for armistice.

Khan’s envoy got a typical response from Dyer: "my guns will give you an immediate reply, but your letter would be forwarded to the Divisional Commander."

Afghans were routed by the Indian troops. In the evening of June 3, my friend Shahzad Bangash’s grandfather, an employee of the Imperial Telephone and Telegraph Department received a telegraph at Thul fort that the war was over. He quickly passed it on to Dyer. With it General Dyers career as a soldier also came to an end. He was quickly relieved of his command, disgraced and discredited because of the Amritsar massacre and died a few years later in England.

It is depressing to know that Pakistan Railways stopped this service in the 1980s and the railway carriages and engines have disappeared from the record books. The City Station, or Jhandi (flag) Station as it was locally known, was an important place of the city in yesteryear. Today its platform is a crumbling mud structure and serves as a cattle shed.

On one side of the closed window of the ticket office one can still find the timetable painted on the wall. Gone are the days when NG 5-UP and NG 5-DN trains from and to Thul would arrive on dot time, so that one could correct their mechanical watches.

Sadly, we were the only ones visiting this ticket office that still advises passengers in English and Urdu to examine their tickets and check fare list before leaving. Professor Iqbal had travelled on this train on quite a few occasions in the past but did not remember when the train hauled passengers on this narrow gauge last. It has simply faded out of memories.

All of a sudden, Laiq Shah appeared from the backyard and introduced himself as the gatekeeper of Railway Department deployed to look after this railway crossing. He had replaced his father who retired in 1969 after 35 years of service in the Imperial railway. He talked about the good old times when the trains arriving on time were loaded to capacity with passengers and the adjoining ground filled with tongas to take them to the Tehsil Gate and the city.

While narrating an interesting anecdote, Shah said in 1951-52 a newly posted stationmaster caught two tribesmen from Tirah who got down from 5-down train without tickets. The tribesmen pleaded that they were penniless labourers looking for a manual job in the town and would pay up for their tickets on return. The stationmaster was about to order their confinement to jail when their fellow travellers intervened to reach a compromise, whereby the tribesmen had to deposit their pagrees (headgear) with the stationmaster as security for a week. The two men returned a week later, paid what was due, collected their pagrees, bought fresh tickets, boarded the 5-up train and disappeared.

The stationmaster thought he had done a great service to North Western Railways by reprimanding the defaulters, and that his strict action would serve as a future warning to other passengers. The matter was forgotten. But not for too long.

Losing their pagrees, even though temporarily, was tantamount to losing their self-esteem. The stationmaster, not knowing tribal ways, had cut across a tribal norm unwittingly -- and had to pay for his folly.

Two weeks later, 10 armed tribesmen mysteriously descended from the train in the morning and disappeared towards the city unnoticed. They returned in the evening, kidnapped the stationmaster, boarded the evening train to Thul and disappeared in the tribal territory.

The news shook the city. A police posy boarded the morning train for Thul in hot pursuit but returned empty-handed.

A month later, the terrified stationmaster staggered into the railway station, with tattered clothes, dishevelled hair and bleeding foot sores. He was so horror struck that it took the entire day to calm his spirits. His escape was less miraculous and more of deceit. His captors would regularly pray five times a day while he would watch them from the confine of his dark cell. One day he pleaded that as a true Muslim he be allowed to say prayer in the jamaat (congregation). Permission was granted. His religiousness earned him the confidence of his captors. So, one night he took more time for ablution than was necessary, till the Isha congregation prayer started. This gave him enough opportunity to slip away in darkness -- three days of foodless rambling in the wilderness brought him to Kohat.

On the request of panic-stricken stationmaster, he was transferred to Lahore. The government placed a permanent police picket at this small railway station for the security of the staff. The two erring tribesmen were never seen again. No tribesmen would now dare to travel on this narrow gauge railway without tickets and the railway staff obeyed the tribal norms as if it was a written law. And life returned to normal in Kohat.

This incident, if recorded, must be rusting in some moth eaten file of the Railway Department.

Memories are usually short. Somehow, only Laiq Shah, the gatekeeper of this railway crossing remembers this incident, as his father was the eyewitness. The diligent stationmaster, who tried to impose the writ of the government but then transgressed the law himself to settle the dispute privately in a tribal fashion, learnt two lessons which must have benefited him in his future life. The foremost was to adhere to the principles of law and act judiciously. The second lesson emphasised on the importance of learning and respecting the local customs and tribal laws especially when the place of posting is the tribal lands.

The story of the stationmaster’s kidnapping is long forgotten in Kohat. Perhaps because the city has more important kidnapping incidents to its credit - for instance, the kidnapping of teenager Mollie Ellis from a bungalow in Kohat cantonment by Ajab Khan Afridi in 1923.

In India, there are a number of narrow gauge railway lines that are fully operative. Three of the famous ones are Kalka-Shimla Railway, Darjeeling Himalayan Railway and Nilgri Mountain Railway and one of them hosted Shahrukh Khan’s famous Chal Chhayyan Chhayyan song for the 1998 film Dil Se. They are now major tourist attractions and have been declared as World Heritage Sites by UNESCO.

However this small City Railway Station of Kohat and the narrow gauge railway line to Thul, which was at the centre of the Great Game in 1919, has passed into oblivion. The only remnants are the crumbling mud structure of the ticket office, the passenger shed now turned into a cattle shed and railway lines made by Barrow Steels of England in 1896 for North Western Railways. Only the gatekeeper Laiq Shah, who resides in the ticket office, lives on, to tell the tales of what once was the Kohat-Thul railway service.

Concluded