Defusing the deeply-entrenched violence from society necessitates recourse to Bacha Khan’s reformist agenda

On January 20 every year, Abdul Ghaffar Khan’s death anniversary passes with occasional events commemorating the socio-economic and political struggle of the legendary nonviolent icon. What we miss is the perennial call of the time at least for a decade now that defusing the deeply entrenched violence especially from Pakistan’s northwest necessitates recourse to Khan’s reformist agenda.

On the socio-economic side, Bacha Khan meant for reforming the Pakhtun society at the grass-roots level and lifting Pakhtuns out of grinding poverty to a path of self-sufficiency. On the political front, his purpose varied from Indian independence to independent Pakhtunistan to genuine provincial autonomy within the Pakistani federation. Nonviolence, a passion with Khan, was more an end in itself than an all-pervasive means to other ends!

At heart, Bacha Khan was a reformist. Education was his major vehicle of change. From 1910 to 1921, Khan opened at least 70 educational institutes in various parts of the then North West Frontier Province, now Khyber Pakhtunkhwa. With Pashto as medium of instruction, curricula comprised the Holy Quran, Hadith, Fiqah, Pashto, Mathematics, English and Arabic. Besides, vocational skills like weaving, carpentry and tailoring also made to the syllabi.

In April 1921, Khan founded Anjuman-i-islah-ul-Afaghana (Society for the Reformation of Afghans). Apolitical and purely missionary, the society undertook to eliminate social evils from Pakhtun society. In order to spread his message in outlying areas, the campaigner extensively traversed all the 500 odd-villages of the frontier on foot and on two-wheeler. One major reason tribal areas are embroiled in violence today is because the British never allowed Bacha Khan to carry out his reforms in the hinterland.

Khan fully comprehended the divisive influence of the British ‘divide and rule’ policy. Back from haj and his subsequent touring of Taif, Mecca, Jeddah, Medina, Palestine, Lebanon, Syria and Iraq, Bacha educated his people with a newfound zeal. He had observed that in these Muslim territories, pan Islamism had morphed into robust nationalism.

Instilling political consciousness and engendering national cohesion among the Pakhtuns were as essential as formal education. To this end, in May 1928, Khan issued the first publication of monthly magazine entitled Pashtun. Promoting Pashto language, its contents covered developments affecting Pakhtuns in India and Afghanistan. Other subjects of the journal were religion, health issues, women problems and Pashto literature.

Taking cue from Congress, Bacha Khan understood that successful mobilisation called for political organisation. The Zalmo Jirga (council of youths) and Khudai Khidmatgar (Servants of God) were geared towards eradicating evils from Pakhtun society and ejecting the British. Khan’s Zalmo Jirga, established on September 1, 1929, targeted the literate youth of his schools. Entrants would pledge to eschew communalism.

Catering to illiterate and the elderly, Bacha Khan formed Khudai Khidmatgars in September 1929. An applicant would take the oath to selfless service to people, strict adherence to nonviolence and among others abstinence from intoxicants. Members of feuding families were barred from joining the organisation until they had their feuds resolved peacefully. Keeping in view easier consensus-building and lesser financial burden on parties, Bacha Khan preferred smaller jirgas to larger ones.

On becoming a Khudai Khidmatgar, one underwent physical exercises and got instructions in political education anchored in nonviolence, skilled in cleaning villages, sanitation techniques, spinning cotton into thread and grinding wheat. Concretely, KK distributed spinning wheels called charkhas among the villagers.

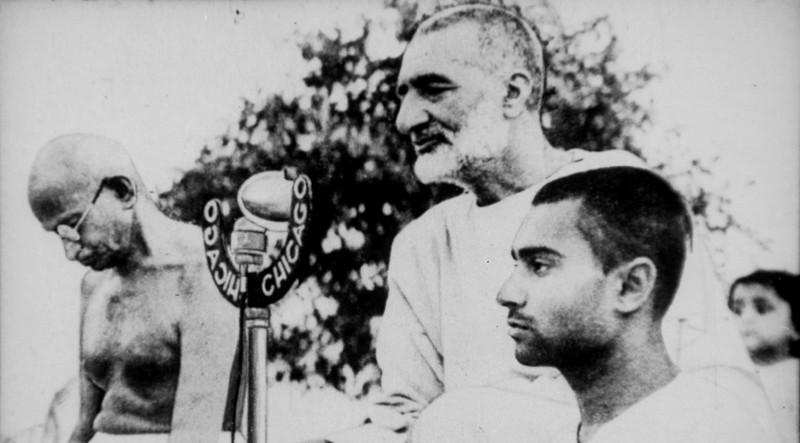

Bacha Khan maintained unbendingly disciplined adherence to non-violence. After KK joined Gandhi’s civil disobedience movement on 23 April 1930, the colonial government’s shooting of unarmed protesters twice in Peshawar and once in Bannu caused 284 fatalities. While Khan ended up behind the bars, KK and Zalmo Jirga were banned.

After Congress decided to support British war efforts in return for independence after WWII, Bacha revoked KK’s association with the party, which was effected on March 30, 1930 with KK retaining its separate identity. He rejoined Congress after it rescinded its earlier decision.

On the Partition eve, having spent 14 years in detention, the unsung nonviolent freedom-fighter cherished the goal of an independent Pakhtunistan state. Since British partition plan envisaged either opting for Pakistan or India, KK boycotted the referendum in the then NWFP. Nevertheless, after independence, KK pledged its allegiance to Pakistan in September 1947. On February 23, 1948, Bacha Khan took the oath of loyalty to Pakistan as a member of Constituent Assembly.

Now the indefatigable Pakhtun nationalist readjusted his Pakhtunistan demand as a modest demand for provincial autonomy only to find him jailed. The nascent state, like its colonial predecessor, preferred the fetish maintaining of law and order over encouraging political participation.

Unsurprisingly, since 1947 to 1977, Bacha spent 15 years in captivity and 7 years in exile. In all, he languished nearly 30 years in jails and 17 years in exile. Countering unbearable hardships with matchless patience, this apostle of nonviolence never resorted to violent means!

In the present scenario, Bacha’s reformist programme would entail ending FATA’s special status by merging it either with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa or made a new province and ending the good and bad Taliban distinction.

With 50,000 plus countrymen perished and in no position to bear another Peshawar school like massacre, the choice is ours: do we need the followers of Bacha Khan, the likes of Malala, or do we want Zia’s protégés, the likes of Taliban? Much like we are reaping what our predecessors sowed three decades ago, our progeny will reap the result of our decisions we make today. It is much like choosing between a paradise and a hell! If we stand for the former, then revisit history, own Bacha Khan and teach him in schools, colleges and universities and madrassas. A passionate Muslim--neither a zealot nor sectarian--Bacha was Gandhiji’s "man of God". A compassionate Pakhtun nationalist and a faithful citizen, Khan’s actions never betrayed his words!