A book that refreshes the memory without putting strain on any other demand

Like so many other millions, Satish Chopra too was drawn into the fascinating world of film music during the years that he was growing up. His family had migrated from this part of the Punjab and he found soothing stability in the film music that he heard. To him, it represented something more, the emotional reconstruction of a society that had gone through much and was on the road to emotional rehabilitation by exercising the options that political freedom presented.

This also happened to be the period when film music was enjoying its more creative phase. Generally, the first 30 odd years, from the 1935 to about 1965, are known as the golden period of Indian film music. The music had special relevance to the lay listeners as they could identify and crystallise their own emotional responses in accordance with the music that they were listening to. It was popular music meant for people on the street and they hummed and reproduced it to give vent to their pent up emotions in a society where the limits of freedom were clearly sketched. The taboos were the main enemy and film music foretold a world beyond that.

Satish Chopra too was one of those millions, and he has now penned those memories in a manner meant for the common listener of music.

Without going into the niceties of music or even film music, he has recorded his impressions about songs, lyrics, compositions and practitioners in the same vocabulary as an ordinary person. And this has made his book an effortless and enjoyable read. It refreshes the memory without putting too much strain on any other demand, like that of identifying the raag, figuring out the taal or labeling the various graces employed. There is plenty of information in the form of snippets, trivia and anecdotal renderings, which make the book correspond with the music which was just meant to be heard, received and enjoyed.

Most of the history of music has been transferred orally from generation to generation is a mythical format. It is full of anecdotes, stories and happenings that border on the incredulous. Fact and fiction run into one another, erasing the boundaries, and this fund of knowledge is all that one has for history. Most of the musicians believe these anecdotal details and are a source of inspiration for them.

The book has been dedicated to those who never received their due, like Master Ghulam Haider, Dina Nath Madhok, Bulo C. Rani, Rans Raj Behl, Moti Lal, Jaidev, Vinod, Vasant Desai, Ghulam Muhammed, Jamal Sen, Sudhir Phadke and Sardar Malik. And the composers that he has written about in relatively more detail are the early ones who were principally responsible for giving film music a definite form. The list includes the early masters, like Pankaj Mullick, Anil Biswas, Khemchand Prakash, Husan Lal Bhagatram, Naushad, Sajjad Hussain, and Shyam Sunder, as well as those not necessarily composers, like Kidar Sharma, Shilendar, Kundan Lal Saigal and Master Madan, who furthered the cause of popular but quality music.

He gives great credit to Saigal for rendering "Babul mora naihar chhuto jaye". Wajid Ali Shah composed this in raag bahiraveen when the British were forcing him into exile from Awadh. It has been sung by Kanan Devi, Ustad Fayyaz Khan, Bhimsen Joshi, Kishori Amonkar, Kesarbai Kerkar, Siddheshwari Devi, Girija Devi/ Shobha Gurtu, Begum Akhter, Jagmohan, Rassolan Bai, Khadim Hussain Khan, Mushtaq Hussain Khan, Padma Talwarkar, and Jagjit Singh but, according to the author, Anil Biswas treated the rendition of Saigal in Street Singer, recorded on film in 1936, as being the best in representing the mood of the composition.

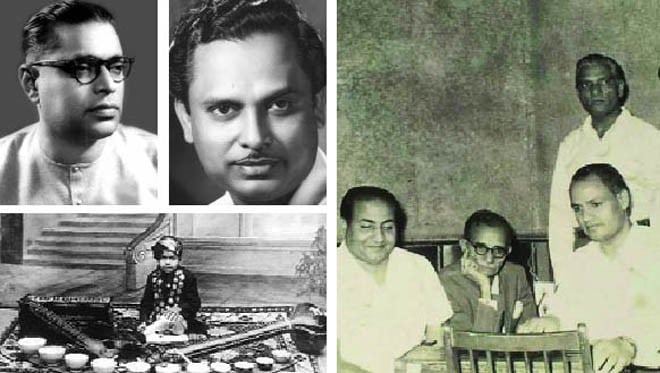

There is also a chapter on Master Madan, a child prodigy who died very young. He was born to a Sikh family in 1927 in a village called Khankhana named after Rahim Khanekhanan, one of the nauratans of Akbar’s court. When Madan gave his first performance at the age of three and a half with a spellbinding dhrupad rendition, Pandit Amarnath accepted him as a shagird. He also composed the two popular ghazals of Sagar Nizami, "Yun na reh reh kar hamay tarsaiye" and "Hairat sey tak raha hai jaaane wafa mujhe".

Till the end of the last century, it was thought that only these two ghazals were recorded or that these two ghazals had survived the ravages of time. But Pramod Dwedi of the Daily Jansatta and Jaspal Singh, the nephew of Master Madan, with great deal of research and toil, discovered six other recordings, "Goree goree baiyaan", "Mori binti mano kanha re", "Man ki man he mein rahe", "Chetna hai to chet lai", "Baghaan wich peengaan paiyaan" and "Ravi dey palle".

Once, when he performed at Shimla, Mahatama Gandhi too was there in connection with a political rally, and very few people turned up because most had preferred listening to Master Madan, who was also performing at the same time.

His fame spread far and wide and he was invited to sing at many places. He was much sought after by the rajwaras as well and was constantly performing. His health suffered because of that and was advised rest -- as he complained of exhaustion and low fever. But his popularity and endless performance routine brought in lots of money and precious gifts, which made the family, neglect the growing health concerns. When he was finally taken to a proper doctor he could not recover and died on June 5, 1942 at the age of 15. He was cremated wearing all his medals.

The sudden rise and then very early death fuelled many conspiracies. It was rumoured that he was poisoned but it was actually the greed of the family and the envy of the rivals that killed this child prodigy.