For a variety of reasons, it was just the right time to view a comprehensive exhibition of printmaking at the Saeed Akhtar Studio

The man who dipped his hands in some coloured liquid (animal blood or pigment) and left the impression on the wall of a cave or a smooth stone was perhaps the first printmaker. These imprints of our prehistoric ancestors’ are found in the caves of Stone Age, calculated to be thirty thousand years old. Since then, the practice of making prints using a range of methods and materials on a variety of surfaces has continued till our times, with some of the most exquisite prints having been created in China, Japan and Europe.

Pakistan joined late and naturally so: the history of printmaking here, or art for that matter, is merely 67 years old. It did enjoy some great moments in this brief period. One was a printmaking workshop conducted in 1967 by Ponce de Leon, an American printmaker, for artists like Ahmed Khan, Marjorie Husain, Saeed Akhtar and several others. These artists discovered a technique and medium that was already practiced in Pakistan but not as a major activity.

The region was known for its rich tradition of block printing on fabric but it was during the Bengal School movement that artists, seeking the indigenous art forms, acquired printmaking techniques from Japan and China, and produced a number of works in woodcut and other such formats. In India, several private presses flourished around 1870 in different parts of the country, producing monochromatic and coloured woodcut prints.

At the same time, contact with the European culture introduced the importance of other techniques of printmaking like lithograph and etching. Ravi Varma was the first Indian artist to establish his own lithographic press at Ghatkopar in Bombay in the last decade of 19th century. Earlier examples of etchings in art became possible when Mukul Chandra Dey (part of Tagore family’s Vichitra Club) went to America in 1916-17 and learnt the technique of etching from James Blanding Sloan.

In our part of the world, Abdur Rahman Chughtai, Safiuddin Ahmed, Mohammed Kibria (two from East Bengal) and A. J. Shemza created works in this format. In European art, printmaking was popular for two reasons. Prior to photography, it provided the facility to make and distribute copies of masterpieces. But after that need was efficiently fulfilled with photographic reproductions, printmaking assumed another role. For people who could not afford high prices of art, here was a possibility to collect original works of major artists.

Thus many families (even in Pakistan) possess signed prints by Pablo Picasso, Joan Miro and Henry Moore. Along with offering art on a reasonable price, a number of modern and contemporary artists including Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg explored printmaking as an independent mode of expression.

In Pakistan, art never drew huge and unrealistic prices till the recent past. Hence the need for a cheaper version of big artists’ work was not relevant. The second important stage in the history of vernacular printmaking was the establishment of printmaking studio and offering this as one of the major subjects at the National College of Arts (NCA) in the early 1980s. Artists and art teachers like Naazish Ataullah, Anwar Saeed and Afshar Malik, under the guidance of Zahoor ul Akhlaq, contributed towards popularisation of printmaking at NCA and in other parts of the country. Their efforts produced a large number of artists working in this genre and many among them started teaching this subject at various art schools.

However in recent years one has witnessed a visible, even if inexplicable, decline in printmaking. The advent of digital prints and computer-related techniques of image making may be one cause, but this is not the only or decisive motive. Several artists known for printmaking and trained in the subject like Anwar Saeed, Afshar Malik, Jamal Shah, Naiza Khan, Sabina Gillani, Laila Rehman and Asmaa Hashmi (the first graduate of printmaking major from NCA) are now working more as painters and engage in printmaking only occasionally.

Thus it was just the right time to view a comprehensive exhibition of printmaking (Sept 9-20, 2014) at the Saeed Akhtar Studio. Curated by Imran Ahmad and Usman Saeed, the exhibition titled Sydney-Lahore included prints from the collection of Cicada Press and Saeed Akhtar Studio along with ‘loans’ from a few other individuals.

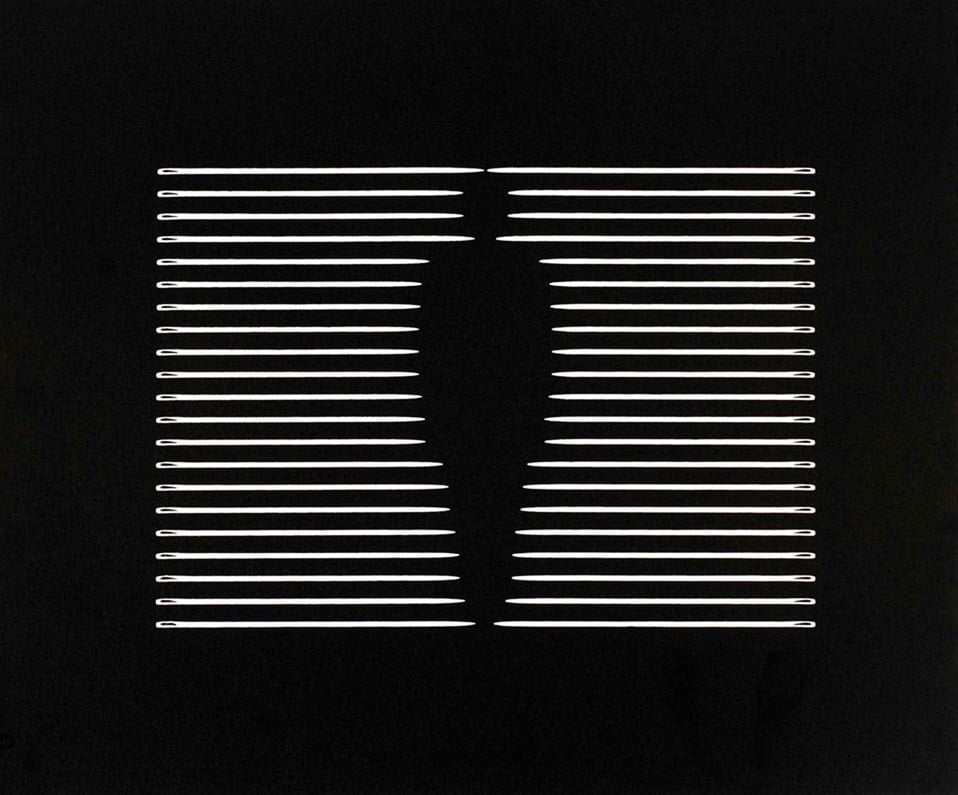

The exhibition, which lay more emphasis on collecting than curating, presented two traditions of printmaking. Prints from Sydney offered a preference for mastery of techniques and tools, mainly found in the works of Michael Kempson, the director of Cicada Press at the University of New South Wales. These relied on the Western and European fixation on precision and accuracy. Compared to them, the Pakistani prints were experimental and diverse, to say the least. One could view works of well-established artists next to students’ exercises, or prints from box-print folios.

The exhibition was important due to the sheer range of names. The history of printmaking or the history of art in Pakistan can be gauged through some of the earliest prints by A. R. Chugtai (Portarit of Dr Iqbal), Shemza (1959) and Jamila Zaidi (1961, 1964). The display also included names such as Zahoor ul Akhlaq, Salima Hashmi, Iqbal Hussain, Meher Afroz, Naiza Khan, Shahzia Sikander and Imran Qureshi. The works suggest how different themes have been tackled in our art, and in different phases of artists’ careers (like Plant 1985 woodcut by Bashir Ahmed, and the linocut Flight by Shahzia Sikander).

Apart from projecting printmaking as a means of making art, the exhibition has raised questions about definitions of art and validity of certain art practices. It also indicates that in the realm of art, no idea, medium and practice is permanent. Art is a course to transform the world around us, but the first and foremost change it brings about is within itself. Thus today printmaking is not limited to merely rubbing ink in a metal sheet or rolling ink on a stone block: it is more about reinventing and incarnating the genre in the guise of digital prints and photography.

Perhaps a new mode of capturing and creating images will modify the notion of printmaking -- from being a craft to an act of addressing profound ideas. Because in the visual arts, a still life or landscape can be a sublime concept depending on how an artist deals with it (as Cezanne employed these themes to address greater formal and pictorial concerns). Otherwise any technique or theme is reduced to a sign of one’s skill and craftsmanship; for instance, one of our artist’s claims to fame is that his woodcuts have more than 100 layers of colour printing but he is hardly bothered about what goes in between those coats of colours.