Hyderabad’s Bombay Bakery is more than a confectionary; it’s a sweet, sensory reminder of another kind of history that has been silenced

(II)

How to make a light and crispy almond macaroon cake? There is, of course, the tedious way of doing this. Making a fluffy batter with eggs, butter, sugar and crushed almonds in a food processor, preheating the oven (if you have one and are not scared of its deep, dark heated interior) greasing the pan, pouring the mixture in and letting it be till you get a cake that trembles; then making its topping, re-baking it into crustiness and so on. You could always write to Zarnak or chef Mehboob or Shireen apa if you don’t get there -- or read Like Water for Chocolate to pick on emotional cues why your cake wont set or rise -- but there is another way too: Go to Hyderabad for a Bombay Bakery cake.

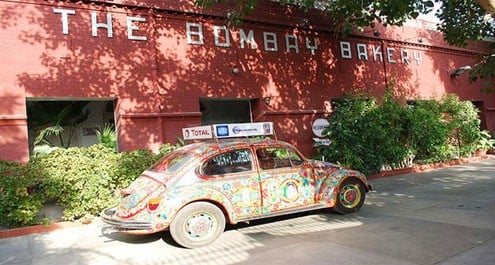

This bakery is located in the high end, Saddar area, in a somber red, tree-lined bungalow, which is home to fourth generation Thadani family, who run the business. This long house was constructed with a bakery outlet in mind -- a shiny black-and-white tiled place with glass display and large glass bottles for cookies. A dour grandfather clock looks at you as you try to peer into the rest of the house for Nasserwanji tiles and the Sindhi peengho or carved wooden swing.

The cakes -- warm chocolate, coffee, lemon, golden butter cream, silvery marzipan, complex sponge and, my personal favourite, almond macaroon -- remain the same in look and taste as when your great grandfather brought one home for your great grandmother since the bakery is over a hundred years old. Cakes and other confectionary is sold in white cardboard boxes with a proud description of the family business, foregrounding its Hindu genealogy.

But, to be honest, would you recognise a Bombay Bakery cake if it didn’t come from such an intriguing looking place -- a bakery guarded by the local police -- and its packaging were taken away? Could you tell if it came from, say, a Shezan chain instead? The point is not to run down BB products that are certainly a developed, distinct taste, but to see how much subtext we read into our food. (Would burgers and pizzas be as popular if they did not carry foreign brand names and were not considered part of the modern American dream?)

I, for one, swear by the macaroon and promise to cherish and to hold till death by overweight do us part but the Bombay Bakery cake has become over the years far more than a deli product. It has taken on the form of tabaruk or prasad precisely because of its Hindu origins and cakes are carried to far off lands as valued tokens to family, friends and neighbours.

The cake has become a signifier, an object, and a signified or the meaning invested in it, if I may please bring Saussure into the boulangerie. It has become more than a confectionary and is a sweet, sensory reminder of another kind of history that has been silenced, subsumed in national narrative, a story with no Arabs in it.

As Dr Mubarak Ali, the famous Hyderabadi historian writes in several of his books and papers on the topic Sindh ki tareekh kia hai? Sindh ki saqafati aur samaji tehreek and several issues of the journal Tareekh, history is a theory, an idea, the politics of whoever is writing it and what the intended effect is on the audience.

Read the first part: Hyderabad Diaries: Looking for Hassan Dars

So there is a secular colonial history of Sindh and a Mughal one, an Arab history of conquest and then the national narrative of Pakistan as an Islamic state counterpuntal to Sindhi nationalist history. Which one is to be believed? According to Dr Mubarak Ali, all should be read to piece together a mosaic of meanings.

The only history of Sindh we are taught in schools today is the Arab version with Muhammed bin Qasim, the heroic conquistador, who introduced Islam to this region. In this version, the local rulers, Hindu at the time, who defended their homeland, are proclaimed villainous.

In the first part of his memoirs, Dar Dar Thokar Khai, Dr Mubarak Ali speaks of living in exile from Hyderabad, Sindh, since he relocated to Lahore, recounting the days when Hyderabad was a small city that could be walked end to end, generating many friendships and many cups of tea in Irani hotels along the way. He recalls to this day how it was a city of gardens and how the roads were washed each morning. We speak of the beauty of Hirabad, exquisite Hindu constructions with balconies of iron filigree, coloured glass windows and doors and stone fountains in the courtyard, but also of Hyderabad as primarily a place for teachers and students with its many bookshops.

The story of Sindh’s partition and the exodus of the Hindu community have been far less documented than the tragedy of the Punjab and of Bengal, when unnumbered refugees left for Bombay from Hyderabad and other parts of Sindh.

One recent book on the subject is Saaz Aggarwal’s Sindh: Stories From A Lost Homeland (2013), who writes of partition, which she calls "vivisection" like Gandhiji did. With rare restraint, she speaks of it as sensory exile, writing about losing the sights and smells and sounds of childhood to make another home somewhere else. She speaks of the shock of umbrellas and the heavy monsoon of Bombay as opposed to the dry heat of Hyderabad summers, where they flew kites in the evening breeze.

She speaks of "getting used to another grain" as wheat was not the staple and giving up on drinking milk which was rationed in Bombay at the time. She speaks of losing the music, gently mentioning bhakti singers like Kanwar Bhagat Ram, who was killed, and an artiste of the classical caliber of Jewni Bai, who was humiliated in partition riots.

Aggarwal has an entire chapter titled ‘Brown Bread from Bombay Bakery’ as part of her westernised childhood and how bread from Bombay Bakery reminds her of her father, both never to be found again.

Dr Mubarak Ali writes about wars of attrition that are not lost on the battlefield but in culture and intellectual terms as well, changing the affected people forever. Surprisingly, Aggarwal writes about how much less "Hindu" their family was in Hyderabad, celebrating only Diwali but participating in other public events like Muharram and several Sikh festivities.

In Hyderabad for Diwali this year, I noticed my Hindu friends are far too secular and suffer it like some of us suffer Eid as a family extravaganza full of rich food and false bonhomie. The boredom of ritualised festivity is lifted somewhat by cakes from the Bombay Bakery made especially for the occasion, ageing gracefully, silently sweet after all these years.

To be continued