A group show at Satrang Gallery, Islamabad strives to break boundaries and overcome tradition as form

In his De Anima, Aristotle identifies the human being as a blinking animal - at once capable of vision but also, and more importantly, able to close his eyes, to choose not to see, and therefore able to reflect. If the outside world registers in our consciousness as a lasting image, it is as much due to our capacity to close our eyes in thought as it is to our ability to see.

In the literary arts since Homer, insight has always been essentially indebted to blindness. At times, Virgil puts his hand over Dante’s eyes in hell, both to protect his pupil from the lacerating vision of sin but also to allow him to learn, as if the moral of the story is best considered with eyes wide shut.

Among all the arts, this paradox of blindness and vision, of light and dark, of exposure and closure, is effectively embodied in the exhibition entitled ‘A-Visible’ at Satrang Gallery, Islamabad.

Artworks are like books, and artists are like authors. The relation between the work and its producer is intertwined with a degree of originality. The character of the oeuvre reveals the character of the artist and vice versa. The two form an inseparable entity, literally a body of work.

‘A-Visible’ presents the works of Amna Ilyas, Heraa Khan and Maha Ahmed. On the edge of political discourse and artistic gesture, their works strive to break boundaries and overcome tradition as form.

Books are sacred objects. Flipping through their pages can provide limitless inspiration. For the majority of people, this inspiration is read, for some it is felt, for others observed and for still others smelled.

I am reminded of an installation, made way back in 1994, by the Chinese artist Xu Bing for an exhibition at the Bronx Museum, called, ‘Brailliterate’, presented in the form of a braille reading room. Borrowed or made-up titles were printed over the original Braille titles unrelated to the actual Braille content of the books. The content was unknowable for most audience members.

In the same way, a blind reader would not know that the information provided to the average audience was completely different from the actual content. The work probed and discussed questions of reading, bias and concealment.

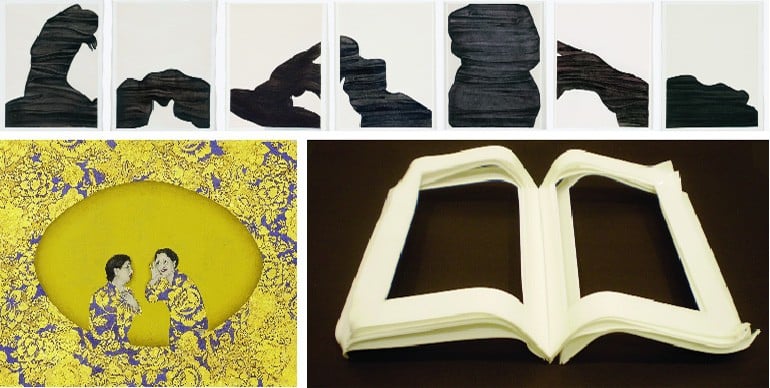

In Amna Ilyas’s ‘books’, cast in Perspex, there is no written text, per se. Her books are then a purely visual, totemic or iconographic work in which the structure and materials are the content. Their physical presence and their weight speak to our deepest inner sensibilities. The very forms speak of knowledge preserved and communicated. They also represent our ability to build on complex ideas.

When Ilyas turns a book into a sculpture, its inner life reaches out. Each viewer is drawn to contemplate memories or visions stimulated by the ‘object’, and then brought back to the material presence of the work. Balancing the power of image, material, and metaphor creates a vibration in the space around it.

Books sans words with lines etched on them, or the text hollowed out - books that defy readability and deny the power of the word - allow the viewer to surmise that Ilyas is interested in blank surfaces, which are in effect the opposite of voids. She almost conforms to the idea adumbrated by Michael Frayn in ‘Against Entropy’: "She took one or two of them down and turned the pages over, trying to persuade herself she was reading them. But the meanings of words seemed to dart away from her like a shoal of minnows as she advanced upon them, and she felt more uneasy still."

With wit and a healthy dose of popular culture, there is a level of playfulness in the appearance and narrative of Heraa Khan’s subjects. Her characters are extracted from her own life, from reality and the subconscious. What Heraa Khan has painted are not female images in a realist sense. They look more like a metaphorical visual language about hedonism in the twenty-first century. In her miniatures, Khan has revealed the fictitious dissolution of ideology, and the characteristics of the body, expressed in their ‘coolness’, gesture, expressionism, dress and make-up.

The artist focuses on the facial expressions and inadvertently, as it seems, has revealed a sort of self-transformation of the post-political bourgeoisie. In her paintings, such an escape becomes an errant scene, which is pleasant and nihilist: the uninhibited bodies, the extreme freedom and pleasure, and the relief experienced by souls after forgetting history.

A mood that is half-romantic and half-tacky overtakes the images, with each background carefully selected to work with the oval composition (laid out in the centre of swirls of flowers, embedded in gold resembling cheap wallpaper) captures its jovial, sentimentalised perfection.

These works reflect on a tradition of kitsch that many families in Pakistan are caught in and present a section of society wholly removed from the caustic scenes of political upheaval in the country.

We see women anesthetised by glamour and make-believe to the realities outside the door. As if by adhering to the prescriptions of society, they do not only get by in the face of oppression but also cut themselves off from a stifling reality turning to an insular world.

Made suffocating by the overbearing smiles and abundant kitsch, we glimpse a comfort zone - accessible to all who are willing to live amidst store-bought sentimentalism and pseudo-romantic wallpaper.

Screens serve to conceal and protect, to separate, shield or filter. Some screens, walls, enclosures, or the lace that covers the face of a woman wearing a burqa, are intangible. Others, social and political frameworks and personal filters of memory or expectation, are less visible and perhaps less noticeable. Maha Ahmed has touched on the notion of making the visible invisible through her miniatures.

Ahmed speaks of the terror that is the underbelly of displacement, a terror of irrational fears and hopelessness that make it impossible to face the difficulties of adjusting.

In her work we see the effective opacity of walls of windows covered in a black cloth, emblematic of barriers beyond which people feel protected and safe. The veiled, undulating female figures are draped in a black cloth following the body silhouette. Depending on the context, the reactions could be contradictory. On the one hand, the drape represents suppression and a severe limitation to experience one’s environment and self. If given a choice, most economically dependent and exploited women would shake this encumbrance off with great relief. However, there’s a significant number who co-opt with the system and social prejudice and regard the veil a symbol of identity and desirability.

Conversely, myopia can also be read within these works as an imperceptible native veil. Maha Ahmed addresses people who had been born with a veil in their eye. A severe myopia stretches its maddening magic between them and the world. Myopia has its shaky seat in judgment. It opens the reign of an eternal uncertainty that no prosthesis can dissipate. Ahmed’s imagery attests to the fact that some people gravely wounded by myopia can perfectly well hide from public gaze the actions and existence of their mad fatality.