It was unfortunate that Allama Iqbal’s mausoleum was closed on his 76th death anniversary due to security reasons. Many who had gone there in the traditional reverence of offering fateha on his barsi were thus rudely shocked and disappointed as they were not allowed to proceed beyond a certain point.

This year, the traditional festivities of baisakhi were severely curtailed again due to the fear of a terrorist attack. Baisakhi is a seasonal festival, a celebration with song and dance of the harvesting of the crops. But, due to the exclusionist approach being adopted feverishly by various sections of the population in the subcontinent, it is now perceived as an exclusive Sikh festival.

Thousand of Sikhs are given special visas to attend the festivities in Pakistan as most of their religious sites happen to be physically located here. However, unlike earlier times, they were rudely shocked that the rituals and other festivities were strictly curbed in places like Eminabad, Hasan Abdal and even in Lahore.

The excuse advanced was the usual security threat.

There is a constant drumbeat of the government wanting to promote tourism in the country. Some of the most revered sites of Sikhism, Hinduism and Buddhism happen to be in the territories now Pakistan. With a more liberal visa policy, the quantum of tourism can increase exponentially, with so many tourists that this country will find it difficult to handle. But there are other concerns and impediments which do not let a more liberal visa policy take effect -- these are more in the mind than in actuality.

This perception growing out of extreme insecurity has caused great harm to the nation’s independent growth of cultural expression.

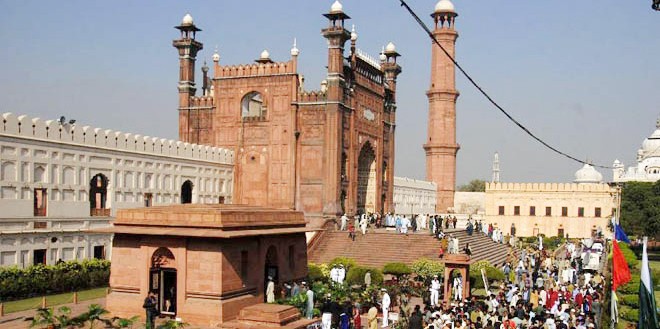

On March 23, Pakistan Day, the monument which supposedly symbolises the beginning of the concerted struggle for the creation of a separate homeland for the Muslims of the subcontinent so that they could live in freedom, practicing their faith openly, and without inhibition, was also closed to the general pubic for the fear of something untoward happening there. For the general people, a public holiday is an opportunity to spend time out in the open with family and friends. This time round it could not be done as the lawns around the monument were cordoned off.

Similarly, in the past few months, the mausoleum of Quaid-e-Azam in Karachi too has restricted access due to security concerns and the people have not been able to spent their leisure hours in the shadow of the dome of the founder of the nation.

When the scale of terrorism widened in the Musharraf era, some consolation was derived from the hope that a democratic government will be better placed to tackle the problem, keeping in view the wishes of the people at large. As was seen in the five years of the democratic government, no relief was forthcoming and the scale of violence multiplied many times over. In the last election, it was again hoped that with the change of command at the top things would improve and the issue that causes violence would be addressed head on. The last year has heard rhetoric which is well meaning; yet nothing has resulted in qualitative terms to make the people feel more secure and visit public places in particular without a thought lurking in the back of their minds of a bomb going off.

In the last decade or so, the properly organised events under the aegis of some private or public body have thrived while those where people at large participate have been either totally banned or severely curbed. The most badly hit have been the various melas and urs across the length and breadth of the country and other gatherings where ordinary folks gather to unwind. The urs of Khawaja Farid, Sakhi Sarwar, Waris Shah, Bari Imam, Bulleh Shah and Rahman Baba are now ghosts of their former hustle and bustle.

The Urdu/Persian poets are not recalled and remembered in the same manner as the poets who wrote in the local languages. Whether it is Khushal Khan Khattak, Mast Tawakali, Shahbaz Qalandar, Shah Latif Bhitai, Shah Hussain or Baba Farid, their urs are, or should it be said, were, grand public occasions where their kalam was also rendered vocally or as accompaniment to dance. The kalam of the Urdu poets is not rendered in the same style except for, say, qawwali. The only kalam of Iqbal which becomes the glory of the public occasion is in the form of qawwali.

Sare Jahan Sey Acha, written around 1904-05, had become popular. It appears from Ravi Shanker’s account that it was also sung and he was asked to recompose it.

One wonders what the original composition was like, who had sung it and whether any recordings have survived or have been lost to history. It is possible that the composition may have been based on the actual recitation of Iqbal.

In Pakistan, this composition is hardly sung and this poem too is hardly even mentioned -- though it was one of Iqbal’s most famous poems in the years that he was alive.

The first vocalists to capitalise on Iqbal’s poetry and name have been the qawwals. It was also considered safe and sanitised by the Radio authorities, which were the main platform for the promotion of music in the first three decades of an independent Pakistan. Mubarak Ali and Fateh Ali made Shikwa and Jawab e Shikwa composed in darbari one of the standard numbers of their repertoire. So often was Iqbal’s poetry broadcast on the radio that Khawaja Mueenuddin lampooned the poems of Iqbal in his play Taleem -e-Balighan, also parodying Sare Jahan Sey Acha.