We are so accustomed to equate language with its script that we think of them both as one entity. No matter what language we speak, we never question the link between the script and language, or connection of sound with the shape. In our concept a certain script is inseparable from a particular language -- for instance Arabic, English or Urdu are all written in their own alphabets.

Actually language evolved much before the invention of writing; thus a spoken word is not dependant on a written shape. But with the passage of time the scripts, instead of remaining merely neutral vehicles to convey and contain sounds, also added new meanings and contexts. Like the difference of Urdu and Hindi is not a divide between two forms of texts, but it is seen as a split between two faiths because of different scripts.

The reason why a language or even a script is connected to a religion owes itself to divine books. For example Sanskrit, Arabic and Hebrew are considered to be sacred languages in which God (or gods) spoke to mortals. We regard Arabic as holy, the language of the Quran, and Arabic script as sacred. So much so there are jokes about illiterate devotees going to the Gulf States and picking some ordinary piece of paper in Arabic, kissing it believing it to be sacred, because it is Arabic.

We do have respect for classical Arabic because, usually, single words from Quran recur in other discourses and printed forms. This tendency has shaped our response towards visuals arts too because, for most of us, Arabic calligraphy is just a sacred art practice for inscribing the words of God. That way we neglect or negate other kinds of Arabic writing of verses or phrases of a different content (or the use of same script to pen lines from Urdu and Persian poetry).

The act of writing, scared or secular, has been judged as a special exercise in Muslim culture because while writing beautifully one is following the Attributes of Almighty, "who is beautiful and loves beauty". In that sense, contemporary calligraphy is a means to deal with two concepts: denoting sacred script as well as writing for the purpose of perpetuating beauty. Many artists and calligraphers are exploring and extending these links of sacredness and aesthetics through letters.

The recent solo exhibition of Jamil Naqsh The Painted Word (held from March 22-27, 2014 by Albemarle Gallery at the DIFC Atrium in Dubai) indicates an artist’s quest in this regard. In the exhibition, coordination between Ayesha Imtiaz of Poetic Strokes and Albemarle Gallery London, his calligraphic works were on display. In these surfaces, one could glimpse the artist’s attempt in liberating the sacred content from its limited reading and providing a wider visual understanding.

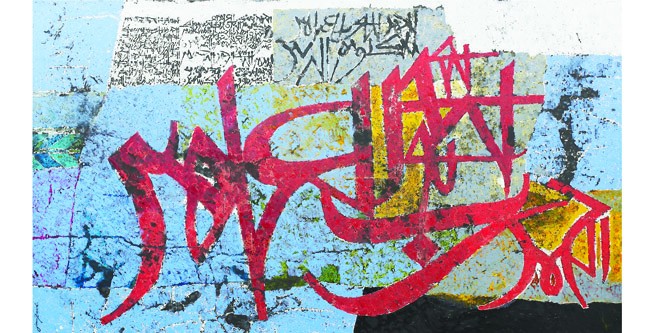

In his paintings, Naqsh moved and manoeuvred the Islamic text in such a way that if you decipher the alphabets (and consequently the message) or can not comprehend the words, you still enjoy the composition, texture and chromatic scheme of these works. In fact these the text is treated in such a manner that it appears as experiments with lines and shapes rather than recognisable writing.

Even if one is able to locate words like God and Prophet and verses from Quran, the artist has transformed these into images which entice a viewer due to their chromatic complexities and formal sophistication. Deft application of paint, thick at some areas while stain at other places, creates sensitive surfaces that, like listening to recitation of holy verses or high poetry, could captivate an audience through the sheer power of their artistic expression.

Like his past works, in the recent exhibition too Naqsh demonstrates his command in presenting variations on a singular theme; in some canvases the subject of calligraphy is stretched so far that it is transformed into abstract imagery. Hence a viewer witnesses the interplay of forms and lines -- that resemble sacred script but provide pictorial pleasure more than any other content.

This aspect of Jamil Naqsh’s works, not different from his pigeon painting or female nudes, is a mark of the artist’s long acquired position -- exploring a subject for its formal possibilities. In a way, this frame of mind can be compared to the philosophy of art from the Muslim societies, in which aesthetic practices are not aimed to prove one’s superiority as a maker or the grandeur of a culture, but these are carried out to invoke human feelings, emotions and thoughts which can be shared by others who may not follow that faith. Like Qawwali, a form of spiritual and devotional singing that has impressed a wide range of listeners because of its artistic merit, the paintings of Jamil Naqsh attract many viewers for their visual excellence, the sacred content notwithstanding. This trait expands the tradition of calligraphy (because the Word of God must be transcribed in an excellent manner) and at the same time alludes to the secular side of Muslim societies in which art was admired for its pictorial qualities.

Jamil Naqsh’s role as the painter of these calligraphic canvases is part of a long tradition but is important because he signifies that religion or religious customs are not devoid of pleasure -- contrary to the misrepresentation of faith in our times. This needs to be re-asserted, even if this phenomenon starts in Dubai!