The last few days in Karachi showed the audacity and striking might of the criminals regarding land management. Architect Salim Alimuddin, director of Orangi Project (OPP), narrowly survived an attack on his life on January 29, 2014. The OPP is a research institution with a focus to help members of poor urban communities in matters of shelter and infrastructure.

A few days later, Mohammad Ishaq, deputy director of Karachi Metropolitan Corporation (KMC), was killed while trying to remove an encroachment on public land. Many public spirited professionals and activists have lost their lives while protecting Karachi’s lands from illegal encroachers in the past. Nisar Baloch and Perween Rahman are two prominent mentions.

Occupation of Gutter Baghicha, the mysterious takeover of park plots all along the city, and encroachments along Northern Bypass and in Gadap are some crucial issues that need attention of the administration.

The policy makers, including members of legislature, view land as a commodity which can be traded to obtain short term financial gains. From an urban planning and sociological perspective, this is not correct. Land is a finite asset which can only be used for public benefits. Its utilisation is best determined through a professionally sound and socially appropriate planning process.

A vigorous urban life cannot be imagined without a proper utilisation policy for land with a detailed master plan to lay down all the proposed functions in relation to existing constraints and potential.

Given the ongoing crisis of infrastructural decay, poor governance and declining urban management capacities, it is crucial that any new venture must be examined for its operational viability and sustainability in the short and long term.

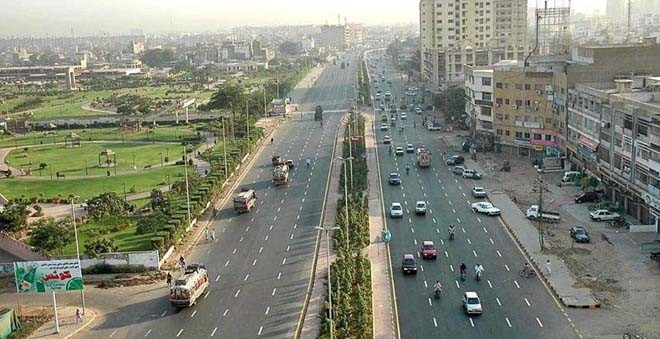

For example, the federal government acquired an exceptionally wide land strip for the construction of Lyari Expressway (all the way from the port to Sohrab Goth along a 16.5 kilometre stretch). The allotment has created the lucrative provision of over 1.8 million square yards of land for real estate. It is important to note that none of these lands have been allotted or utilised according to any openly pursued or applied land use policy for the city.

Similarly, the government has made the master planning department subservient to the building control authority. This is against the standard norm of the land and construction management. The building control bodies follow the prescriptions of master plans -- not the other way round. Such a professionally dubious move can render the whole apparatus of land management a laughing stock in front of stakeholders!

Decision-making pertinent to urban lands has remained highly centralised. As per rules, the chief minister possesses the discretionary power to allot land to any party as he deems appropriate.

It is deplorable to note that these powers have been used most injudiciously in the past. It was reported that from 1985 to 1993, four chief ministers allotted land in Karachi worth more than six billion rupees to cronies or party favourites. The institutionalised procedures of land allotment are also not free from corruption.

The standard procedure is through balloting. People are free to fill any number of application forms they can afford. Thus, rich people file dozens of applications with different names of family members, relations and even servants. The probability of a computer ballot automatically increases the chances of the rich instead of the poor and needy, who file only one application with great financial hardship. As a result, schemes for low income groups become the high ground for speculation.

It was found that the land policies do not reflect the range of quasi-legal situations existing between formal and informal housing. Various intermediate situations have been discovered in the land and housing scenario which cannot be described as legal from the statutory standpoint. As per standard definition, the land or housing which is formally registered through the offices of registrar, after completion of formalities related to the title are recognised as legal properties. According to another definition, the property which can be accepted by a housing finance institution for mortgage financing is a legally valid property.

Spot field studies have shown that there are many lacunae where land and housing units fall short of meeting any of the two conditions. In reference to land, the plots floated in any scheme by the development authorities, legally constituted cooperative societies. Legality of such land parcels is only verified and accepted when the leasing conditions of the concerned neighbourhood/locality are completely fulfilled.

Katchi abadies which have been approved for regularisation but await the initiation of the leasing process; neighbourhoods which await the notification of amelioration plans; localities where change of land use has taken place and areas that have a change of status or jurisdiction are only a few types which cannot be compared with a normally leased area. Owners and prospective buyers have to suffer due to indifference of planning and development agencies. However powerful groups acquire such properties at lower prices and harass the stakeholders, including legal heirs, to submit to their demands.

Land and housing delivery mechanism is so designed that speculation automatically evolves in the process. Land development agencies from the civilian and military domain allot land parcels at a very low selling price. As the owner completes the formalities, he already possesses the opportunity of delaying construction and accruing profits on idle land. Since powerful interest groups benefit from this in-built procedural defect, they are averse to changing the practice.

Regulatory controls in the form of non-utilisation fees or any other form of levies are either non-enforceable or too miniscule to bother the property owners. A simple outcome is the artificial rise in property demands that results into a rush supply of land and housing without any urban planning. Land sales along Super Highway, DHA City and space along major transportation projects are examples. These instances render land management and control an even more uphill task.

It may also be understood that an absolutely uncontrolled market mechanism soon becomes a detrimental entity for the stakeholders themselves. In Karachi, the impotence of land control bodies has been historical. Vested interests, in connivance with government functionaries, have managed to keep planning agencies and building/town planning control departments separate from each other. Thus urban planning, wherever and whenever performed, only becomes a ritual. Nobody is bound or regulated to follow its prescriptions.

The current state of affairs demands various actions without any further delay. It is an established fact that land is a finite asset which requires very carefully utilisation, largely on the basis of social needs. Any land transaction that is initiated must be finalised after inviting views and observations from the concerned stakeholders.

To instill transparency in the routine processes, the various government departments -- including the military authorities -- must be requested to publish the details of the land owned or controlled by them. The provincial and city government must create an autonomous planning agency for Karachi to deal with land management, infrastructure and planning issues for the city. This step shall greatly help streamline the otherwise haywire scenario of misappropriation and ill-managed utilisation of land in Karachi.