Komail Aijazuddin’s paintings are not perfect as far as the level of drawing is concerned; there is a lot of repetition of theme and most surfaces are under-painted. But these works do indicate an aspect of our existence that has been easily forgotten. One finds human bodies placed against Islamic geometric patterns, both ending in drips. These figures vary in terms of their identity -- ranging from divine deities to ordinary characters from around us.

Some of these figures’ appearance and modern costumes is deceptive because, in their postures, they echo historic personalities i.e., crucified Christ or Madonna holding Jesus after His descent from the cross etc. Similarly, the woman playing a musical instrument may appear contemporary but her six arms remind of an Indian goddess.

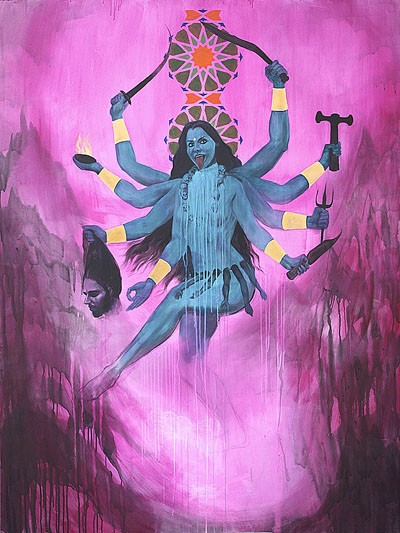

Along with these symbolic figures, other frequent images in his painting are of Buddha, Kali and Ganesh.

Most of these images are composed against or with Islamic motifs. Even though a few Buddha forms have halos at the back of their heads instead of Islamic designs or a triptych is enclosed in a wooden window frame with intricate carving, all of Aijazuddin’s imagery relates to a religious past that survives and pulsates till this day.

Thus, in a way, it becomes irrelevant to criticise or comment upon his craftsmanship or the ability to paint (he has demonstrated both in his earlier works exhibited at Canvas Gallery and other places). The latest canvases suggest something different -- a content beyond and bigger than mere formal or pictorial concerns. It is to recall and reassert our displaced history which includes not only a Muslim past, but other, Dravidian, Aryan, Hindu, Jain, Buddhists, Sikh and Christian heritages too, since this region has been ruled or populated by followers of all those creeds during its 5,000 years of recorded history.

Ironically, our society today has reduced itself to a selected segment of its past. While studying history, we normally neglect those epochs which require us to admit the superiority of Hindu civilization, sophistication of Buddhist art, grandeur of the pagan past from Mohenjodaro and examples of Christian conquests. This attitude towards the past owes less to a religious identity and more to our idea of nationhood which, after 1971, became more embedded in a Muslim nationhood.

Such an approach makes us overlook the fact that a visible section of population of various faiths lives in this country, providing diversity in terms of festivals, architecture, art, food and dress. Our cities, town and villages have temples and cathedrals which enrich architecture of this soil. Similarly, several religious festivals such as Christmas, Easter, Holi, Diwali, Dusehra and Baisakhi add flavour to our monotonous existence.

Yet the country must concentrate on its Muslim character and reject every other tradition, custom and ritual. This surge is equally fashionable in the elite that finds solace in collecting and reading books by Rumi and Khalil Gibran, not realising that the surname of the former suggests his Italian origin, while the latter was a Lebanese Christian.

This attitude is understandable for a large section of population which grew up reading curricula designed to serve the state’s version of facts, and is regularly fed on the media which propagates a culture of hate for the Other -- Hindu India, Christian Europe and atheist America. But it seems a number of writers and artists too are moving away from the richness of our culture/heritage. Perhaps Intizar Hussain is the only leading writer who has been consciously using Indian myths, Buddhist tales and Biblical stories in his works of fiction. Along with him Ibn-e-Insha and Jamiluddin Aali produced poetry in the format of Indianised Dohas. In the visual arts, one recalls the canvases of Laila Shahzada, surfaces of Sadequain and paintings by Jamil Naqsh in which Hindu or Buddhist (and Christian imagery) have been employed.

Today, artists are not inclined to incorporate that aspect of our history, even though they are keen to explore the past in the genre of miniature painting. Yet, for a majority of them, miniature comprises of and is confined to Mughal examples.

Besides painters, authors, and participants of political shows, two other factors are expanding our narrow notion of identity. First, a market that is selling alien ‘products’ such as Christmas and Valentine’s Day and other festivities which generate a lot of money. Second, the entertainment industry which moves beyond borders and has been demolishing our limited views of life; from Turkish soap operas which have amended our concept of Muslim society to Bollywood films which have transformed our culture.