In Pakistan’s political folklore, Iskander Ali Mirza carries a reputation forged by repetition rather than examination. He is cast as the man who ‘invited the army into politics’, the civilian who opened the door to martial rule, from whom later rulers inherited a battered democracy.

Yet like so much in our inherited historiography, this carefully crafted caricature says less about Mirza and more about the needs of those who came after him. A nation that excuses dynastic capture, institutional plunder, offshore accounts, and rent-seeking politics finds it remarkably convenient to place the burden of original sin upon the one founding figure who did not treat the state as private stock, did not create a family empire, and died in exile without wealth, properties or a patronage network. It is time to revisit a legacy hurriedly buried to sanitise others.

Mirza was not a romantic democrat, but he was a serious republican. He believed Pakistan required order, institutions and administrative discipline before parliamentary theatre could mature into a democratic culture. His formation was in the exacting world of colonial military training and political service on the frontier; he came to public life not through slogans but through the grinding mechanics of governance. As Pakistan’s first defence secretary, he built the early command and security structures that allowed the fragile new state to survive a war in Kashmir, refugee upheavals and internal disorder. He understood intelligence, frontier management and civil-military coordination long before they became fashionable concerns. Later, as governor-general and then president, he was not a figurehead but a hands-on custodian of a state struggling to define itself.

Much has been written about Mirza’s authoritarian disposition and very little about the strategic clarity that marked his tenure. He recognised Pakistan’s structural vulnerabilities: a hostile eastern neighbour, an unsettled north-western frontier and a brittle economy. His foreign-policy alignment with the West was no ideological romance but a bid for security guarantees and capital in a world still carved by imperial aftershocks.

On the foundational question of water, he refused sentimentalism and pushed for firm guarantees during the Indus Waters negotiations when international pressure urged ‘trust in goodwill’. Pakistan’s later acquiescence to unfavourable terms was not Mirza’s doing; he demanded rights and storage with a clarity missing in much of what followed.

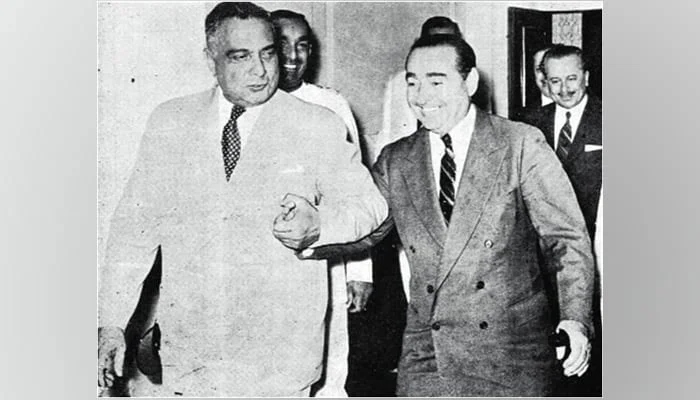

And then there is Gwadar – an achievement so immense that its absence from our political consciousness speaks volumes about our national memory. In 1958, under Iskander Mirza’s presidency and prime minister Feroz Khan Noon’s government, Pakistan acquired Gwadar from the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman. It was not inevitable, nor was it universally supported. It required vision, diplomatic effort and financial commitment at a time when Pakistan was hardly flush with reserves.

Today, Gwadar sits at the heart of Pakistan’s maritime strategy and the China–Pakistan Economic Corridor. Whatever else one may think of Mirza, he quite literally expanded Pakistan’s sovereign map. History rarely grants leaders the opportunity to make additions of such magnitude. Mirza seized that moment. Many who followed shrank the state in dignity, if not in territory.

Critics will point, rightly, to October 1958. Mirza abrogated the constitution and imposed martial law. It is an act that demands scrutiny, not apology. Yet motives matter in history.

According to Mirza’s memoirs, “General Ayub Khan did not like my declaration that martial law must be lifted by 7/8 November. On October 17, he issued a statement as follows: “There seems to be a fear in the minds of the people that if martial law is lifted soon the old order will return…. Let me assure everyone that, whereas martial law will not be retained a minute longer than is necessary, it will not be lifted a minute earlier than the purpose for which it has been imposed has been fulfilled.”

It would take a clever man to understand when the “not a minute longer… not a minute earlier” time would arrive. The Times interpreted the statement with the headline MARTIAL LAW TO BE RETAINED (October 18, 1958).”

He believed Pakistan’s political class had devolved into factionalism and intrigue, and that temporary emergency powers could reset the system. His error was not authoritarian appetite but misjudgment – trusting that the military would remain subordinate to civilian authority. Ayub Khan had other plans. The irony is stark: the man accused of ushering in military dominance was its first casualty, exiled and erased by the very institution he thought he could harness.

This does not vindicate the abrogation of constitutional rule. But it does demand proportion. Pakistan has endured leaders who hollowed institutions while preaching democracy; who enriched themselves under the banner of public service; who treated governance as inheritance and the treasury as private treasury; who made foreign dependence a governing method and patronage an organising principle. None of them died in quiet obscurity abroad, buried in a foreign land because their own nation refused them final repose. Mirza’s life ended without wealth, without monuments, without political heirs. His fall was steep because his power rested on office, not networks; on state authority, not personal capital.

If history is to be honest, it must ask a question we have long avoided: what precisely did Mirza take from Pakistan? And what did many who followed him take instead? The comparison is not flattering to those we routinely celebrate. Mirza’s flaws were constitutional and philosophical. His virtues were integrity, austerity, strategic foresight and a republican seriousness about statehood.

He made one catastrophic bet on the institution he believed essential to Pakistan’s survival. He lost. The country inherited the consequences, but it also inherited a lesson: state-building demands more than slogans; it demands discipline, honesty and the willingness to be unpopular in the short term for the sake of a durable republic.

We may disagree with Mirza’s methods, but we cannot ignore his intentions, nor deny his accomplishments. He expanded the state, defended its sovereignty and refused to personalise power. In an era where politics increasingly resembles a business syndicate and dynastic entitlement is mistaken for public legitimacy, his example – stern, flawed, yet uncorrupted – invites reflection. Was Iskander Mirza the end of Pakistan’s early promise, or the last sentinel of a republic that never truly arrived?

Perhaps our tragedy is not that he acted, but that those who replaced him learned to survive power rather than serve it. History owes Mirza a re-reading. Pakistan owes itself the courage to confront the gap between those who built the state and those who later consumed it.

The writer is the author of ‘Honour-bound to Pakistan in Duty, Destiny and Death.

Iskander Mirza. Pakistan’s First Elected President’s Memoirs from Exile’. He can be reached at: syedkhawarmehdi1812@gmail.com