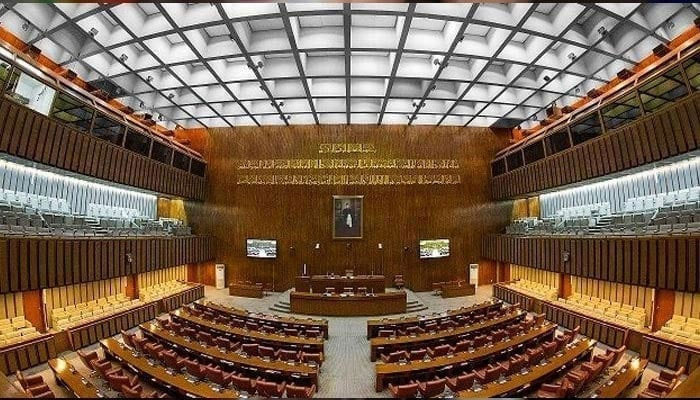

In the not-so-grand scheme of constant constitutional amendments, now the government has presented the 27th Constitutional Amendment Bill in the upper house of parliament, shortly after its approval by the federal cabinet. The bill proposes the establishment of a Federal Constitutional Court, revisions to the process of appointing high court judges and reforms to the military leadership structure. The bill has been referred to the Senate Standing Committee on Law and Justice, though the PTI declined to join the proceedings, describing the process as a ‘pre-decided’ exercise. The amendment had already been foreshadowed via a social media announcement by PPP Chairman Bilawal Bhutto Zardari. Early drafts reportedly included controversial changes to the National Finance Commission (NFC) and a move to return education and population planning to the federation, both seen as potential rollbacks of the 18th Amendment. However, the PPP agreed to support the amendment only on three points: amending Article 243, establishing a constitutional court and managing judges’ transfers through proper consultation.

While observers say the initial outrage over an alleged rollback of the 18th Amendment may have been something of a smokescreen, they also feel that the real intent may lie in the restructuring of the judiciary and the revision of Article 243, which concerns the command of the armed forces. As per the tabled bill, the post of the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Committee (CJCSC) will be abolished and replaced by a new title: ‘Chief of Defence Forces’ (CDF). The current army chief is expected to assume this new role upon the completion of the incumbent CJCSC’s term in November 2025. Another provision proposes that, upon completion of their command, the federal government shall determine the duties and responsibilities of any field marshal, marshal of the air force or admiral of the fleet with the same immunity provisions as those applicable to the president under Article 248. Proponents argue that these changes strengthen the central command structure of the military – a necessity, they say, given Pakistan’s ‘dangerous neighbourhood’ and its fraught relationships with India and Afghanistan.

But the real controversy lies elsewhere. The proposed judicial reforms, many observers warn, could render the Supreme Court toothless by creating a parallel court with constitutional powers. The new Federal Constitutional Court would take over certain functions of the Supreme Court, with equal provincial representation and its chief justice serving a three-year term. Crucially, the president and prime minister would have a decisive role in appointing judges, while parliament would determine the size of the new court. These changes, critics argue, strike at the heart of judicial independence. The proposed transfer of judges and the concentration of appointment powers in the hands of the executive are being viewed as attempts to bring the judiciary firmly under government control. While the amendment is being sold as a reform to address the backlog and pendency of cases, those explanations ring hollow. To most legal experts, this appears less about efficiency and more about consolidation – a civilian-led effort to strip the judiciary of its autonomy under the guise. One is not sure whether there will be changes to the bill that has been presented, but going by most legal accounts, in its current form, the 27th Amendment could very likely be a constitutional undoing – a worrying development in a country where the balance of power has already been skewed for far too long.

-

State institutions ‘fail’ to perform constitutional duties: KP CM

-

CTD orders psychological testing of police on VVIP security duty

-

Navy busts drug consignment valued at $130m

-

Three ex-secretaries in race for ETPB chief post

-

Punjab govt forms 71 JITs to probe cases against banned TLP

-

Some UNSC members ignoring broader reforms, seeking privilege: Pakistan

-

PAC body discusses non-recovery of Rs15bn gas cess

-

Pakistan received $2.29bn foreign loans in first 4 months of 2025