Kabul river dams may deepen Pakistan’s water woes in early Kharif

ISLAMABAD: The construction of dams or barrages by Afghanistan on the Kabul River system could significantly affect Pakistan’s water availability during the critical early Kharif season, experts and officials have warned.

According to estimates, Afghanistan could develop 2.5 to 3 million acre-feet (MAF) of water storage capacity on the Kunar and Kabul rivers, allowing it to irrigate vast tracts of agricultural land.

Pakistan currently receives an average of 17 MAF of water annually from the Kabul River. Should Afghanistan proceed with its planned reservoirs, Pakistan’s inflows could drop by about 3 MAF, reducing total availability to 14 MAF per annum — a shortfall of nearly 16 percent.

Officials from the Indus River System Authority (Irsa) and the Ministry of Water Resources underscore the importance of Kabul River flows during the early Kharif period (April 1 to June 10), when the Tarbela Dam often hits its dead level and the Indus River carries minimal storage. The Jhelum River also provides vital support during this lean period, though its contribution alone is insufficient to meet the sowing needs of key agricultural regions.

“After June 10, as snowmelt from the northern catchments increases, flows in the Indus begin to rise, leading to the gradual refilling of Tarbela reservoir,” explained an Irsa official. “But before that, Kabul River inflows are essential. Even a 3 MAF reduction could disrupt sowing in Sindh and southern Punjab when Tarbela is at its lowest.”

Recent reports suggest that India has pledged $1 billion in financial and technical assistance to Afghanistan’s Taliban-led administration, ostensibly to support water and infrastructure projects. However, senior officials in Islamabad see this move as a political gesture ahead of India’s Bihar state elections, rather than a practical development initiative.

“Anti-Pakistan sentiment has long been a rallying point for India’s ruling BJP,” said a senior energy ministry official. “These announcements are aimed at domestic political gain rather than fostering genuine regional cooperation.”

India, the official added, has already unilaterally suspended key provisions of the 1960 Indus Waters Treaty, manipulating flows of the Jhelum and Chenab Rivers — actions that Pakistan regards as violations of international water law. Pakistan’s leadership has warned that any attempt by India to divert or restrict flows destined for Pakistan, outside of flood conditions, would be treated as an “act of water aggression.”

Even so, experts doubt that the Taliban regime possesses the technical or financial capacity to build large-scale hydropower or irrigation dams. “Constructing a major reservoir on the Kunar or Kabul rivers is an uphill task,” one senior official noted. “Given the current political and economic realities, it is highly unlikely that such projects will materialise soon.”

When the Chitral River crosses into Afghanistan, it becomes the Kunar River, contributing nearly 50 percent of the Kabul River’s total flow. Owing to its steep gradient, Kunar offers potential dam sites — but any alteration of its flow would raise sensitive riparian rights issues between the two countries.

Pakistani officials clarified that earlier proposals to divert the Chitral River within Pakistan — before it enters Afghanistan — remain confined to documents. “Under international conventions, Pakistan should not unilaterally divert transboundary rivers,” an official said. “Afghanistan, as the lower riparian on the Chitral (Kunar) River, has legitimate water rights that must be respected.”

However, once the Kabul River re-enters Pakistan, the positions reverse — Afghanistan becomes the upper riparian and Pakistan the lower riparian. “If Pakistan were to divert Chitral waters, India could use that as precedent to manipulate the Chenab or Jhelum flows — something Pakistan can never accept,” the official emphasized.

Experts argue that both countries must preserve their respective water rights through dialogue and cooperation, avoiding unilateral actions. Afghanistan’s growing population and expanding agricultural needs make its pursuit of water storage understandable, but Pakistan’s established and historic water uses from the Kabul River must remain protected.

Officials contend that Pakistan’s vulnerability to upstream developments could be drastically reduced by expediting domestic water storage projects such as the Diamer-Bhasha and Kalabagh Dams. “With adequate storage, Pakistan would be far less dependent on the timing of Kabul River inflows,” an Irsa expert said. “It would also enhance national water security during the dry early Kharif window.”

Some Afghan policymakers might, in response, argue that Pakistan already enjoys sufficient surface and groundwater resources and should not oppose Kabul’s efforts to harness its own. Islamabad maintains, however, that under the principles of prior appropriation and equitable use, its existing water rights must remain safeguarded.

No formal water-sharing treaty currently exists between Pakistan and Afghanistan, despite sporadic discussions spanning two decades. Several joint working groups were established in the past, but tangible progress never followed.

Officials acknowledge that initiating structured dialogue remains difficult, as most major world powers have yet to recognise the Taliban government. “Negotiating a binding water treaty with an unrecognised regime is diplomatically untenable,” a senior official from the Ministry of Water Resources said.

Pakistan also appears reluctant to accept the World Bank as a mediator, citing concerns about the institution’s influence by Indian lobbying. Given these factors, the initiation of a Pakistan-Afghanistan Water Treaty appears highly unlikely in the near term.

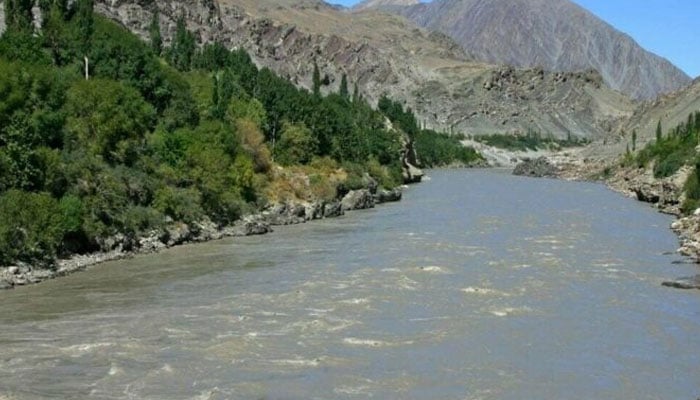

The Kabul River has long symbolised interdependence between Pakistan and Afghanistan — a shared artery sustaining agriculture, urban life, and hydropower generation on both sides of the border. But as both nations grapple with rising populations, climate variability and political uncertainty, the potential for tension over shared waters is growing.

Without structured engagement and long-term water management frameworks, experts warn, the Kabul River could shift from being a source of sustenance to a source of strain, deepening the region’s already complex hydropolitical landscape.

-

State institutions ‘fail’ to perform constitutional duties: KP CM

-

CTD orders psychological testing of police on VVIP security duty

-

Navy busts drug consignment valued at $130m

-

Three ex-secretaries in race for ETPB chief post

-

Punjab govt forms 71 JITs to probe cases against banned TLP

-

Some UNSC members ignoring broader reforms, seeking privilege: Pakistan

-

PAC body discusses non-recovery of Rs15bn gas cess

-

Pakistan received $2.29bn foreign loans in first 4 months of 2025