Some lives become mirrors of history, reflecting the great upheavals of their time not in grand gestures, but in quiet moments of loss, longing and unexpected grace. My father, Imtiazullah Siddiqui, a retired Pakistan Air Force Officer, who passed away on October 13, 2020, was one such man. His personal journey was forever intertwined with the twin partitions that reshaped South Asia in 1947 and 1971.

The year was 1952. A twelve-year-old boy pressed his face against a train window as it carried him and his older brother from Allahabad to Karachi, travelling via Munabao to Khokhrapar. The partition of 1947 had already redrawn the maps and scattered families across new borders, but for young Imtiazullah, the moment that would etch itself most deeply in his memory was not the trauma of displacement but a glimpse of beauty: the Taj Mahal rising in the distance. He promised himself that one day he would return to stand before it to understand why it moved him so deeply from afar.

Life, as it often does, took him elsewhere. Abbu joined the Pakistan Air Force. But the planes that gave him wings to fly also made him earthbound in ways he hadn't anticipated. The rivalry between India and Pakistan meant that his childhood promise would remain forever unfulfilled. As the years passed, his hearing began to fade, an occupational hazard for air force officers of his generation, but his memories remained sharp, particularly those tied to the second great rupture of his life.

The events of 1970 and 1971 brought another kind of partition, one that left deeper personal scars. As political tensions escalated between East and West Pakistan, Abbu witnessed something that troubled him profoundly: his coursemates from the then-East Pakistan were separated from the brotherhood they had once shared.

Among them was a Bengali officer, his coursemate Atma Wajid, whose quiet dignity under impossible circumstances stayed with Abbu for life. When Uncle Atma's wife was admitted to the Combined Military Hospital, alone and pregnant with their first child, she faced her most vulnerable moment in isolation, as her husband was not allowed by her side. My mother stepped in, sat with the young woman through her labour, brought her home-cooked meals and offered the human comfort that institutional policies had denied. But the baby did not survive, a loss born of impossible times.

Through it all, Uncle Atma said nothing. His patience, his grace under such devastating circumstances, left an indelible impression on Abbu. Here was a man, he would later reflect, who possessed a kindness and decency that transcended the political storms swirling around them. After the war, Uncle Atma returned to the newly born Bangladesh and the two friends lost touch. But the memory of that decent, patient man became both a treasure and a burden Abbu carried for nearly five decades.

In 2019, as age began to close in, Abbu grew desperate to find his old friend. Perhaps it was the approaching shadow of mortality, or simply that some debts of the heart grow heavier with time. With persistence and the help of his other coursemates, he finally obtained a phone number.

The phone call that followed became one of the most moving moments of Abbu's life. Despite his hearing loss, Abbu managed to communicate with his friend, speaking privately on the porch, away from family. When he returned, I saw something I had never seen before: a shadow of tears in my father's eyes. But there was also relief, great relief. Uncle Atma had built a good life in Bangladesh, establishing a business and raising four sons and two daughters who had all found success. The conversation brought news that the friend had not just survived but thrived, and more importantly, that he harboured no bitterness.

Perhaps my father had hoped to apologise for the injustices of 1971 at the hands of the system they had both served, but which had treated them so differently. Or he simply needed to know that kindness had endured. Whatever it was, that conversation lifted a burden he had carried for half a century.

In his final years, Abbu spoke often of two wishes. He wanted to visit India, just once, to see the Taj Mahal and then to visit his original home in Allahabad, a city at the heart of the freedom struggle overlooking the Ganges-Yamuna Doab. He wanted to retrace the train journey of 1952, but in reverse. His second wish was to visit his friend in Bangladesh, to sit together as old men and make sense of the history they had lived through. Neither wish would be granted. The borders that had been drawn in blood remained largely sealed, and the diplomatic realities between the nations meant that some reunions would remain impossible.

My father carried his era's contradictions within himself: a refugee who became a defender, an air force officer grounded by politics, a man who witnessed both the cruelty and kindness possible in times of upheaval. His life spanned the great divisions of the subcontinent, but his character was defined by his refusal to let those divisions poison his heart. In an age of rigid nationalism and hardening borders, he held onto a more complex truth: that decency transcends politics, that friendship can survive the harshest historical ruptures and that sometimes the most important journeys are the ones we make in our hearts when we cannot make them with our feet.

His story and countless others are a reminder that behind every great historical event are countless personal journeys, stories of promises made by children looking out train windows, of friendships tested by political storms, of wives who show kindness to strangers and of men who spend their final years trying to reconnect threads that history had severed. When Abbu passed away on October 13, 2020, he took with him the unfulfilled dream of standing before the Taj Mahal but also the satisfaction of knowing that his friend had found peace and prosperity. In a life shaped by partition, perhaps that balance of a dream deferred and a friend rediscovered was its own kind of completeness.

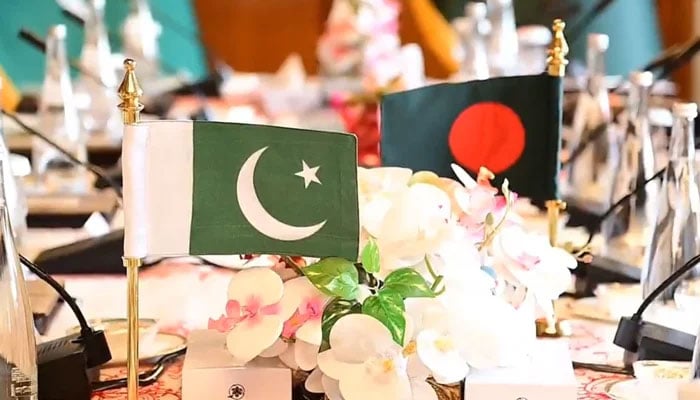

Were he alive today, Abbu would have rejoiced to witness history’s course correction. Pakistan and Bangladesh are now on the path to restoring their relationship, with direct flights set to resume soon. Like many of his friends and coursemates, my father’s legacy lies not in the borders he couldn't cross, but in the bridges he maintained in his heart across decades and nations, proving that some bonds are stronger than the forces that seek to divide us.

The writer is an executive producer at Geo News.