A legend of classical music muses over its developments through South Asian history

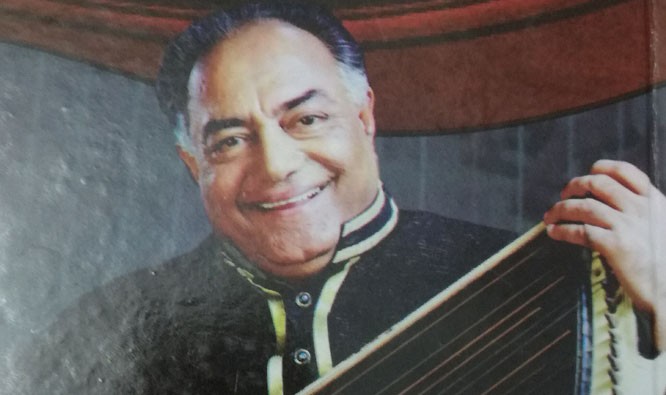

Ustad Badaruz-Zaman is the leading musicologist of the country. The aficionados of classical music - inclined towards classical music concerts – have seen him perform at various forums. These days very few programmes featuring classical music are held, especially on television, but in the past he was a regular performer along with his brother Qamaruz-Zaman.

More than a performer he has been an avid student of music and has written a number of well researched books on various aspects of our music. Hailing from a family of non-musicians, with no lineage of hereditary musicians i.e. without any advantage or headstart; he has persevered to acquire the nuances of classical form, which are inaccessible even to many proficient in the intricacies of a mysterious, complex form of music.

In his latest books, he has kept up with the strict traditions of scholarly work, paying heed to oral tradition and hearsay without accepting it as an article of faith. Instead, all his works are credited sources - as should be the case serious scholarship.

For researchers in Pakistan it is a lonely path. There are very few opportunities to carry out research. In an environment, hostile to serious scholarship of any subject – above all of music -the general tenor is to discourage it. It is often said that since music becomes realisable only in practice, its theoretical underpinning is mere wordplay. The resources, both financial and intellectual, are therefore not easily available. They have to be unearthed, which is taxing and difficult but at the same time highly rewarding. The reward comes with pain, and it is the Pakistani music and people which benefit from the likes of Badaruz-Zaman. For it is a challenge only the most fanatical of musicians will accept. Striking balance between the practice of music and its theoretical understanding, is an art in itself. In this book, the author has not only accepted the challenge, but also met with great success.

While the book has been written keeping music taught at educational institutions in mind, the title of the book suggests a medley of themes and subjects. Surmandal meaning a mandli of surs - a place a where tune resides or an area it comes to inhabit.

Zaman begins by sharing views of various well-known scientists about the relationship between musical notes and colours. There is an integral connection between hue and tone, recgonised in a plethora of ancient texts. Moreover, it is a matter of tradition and mythologized renderings - a connection which Zaman has pointed out. One just wishes he had explored this in more detail, rather than just mentioning shades of colours, by the likes of Newton.

Next he moves on to some of the contributions by Tansen - a 16th century composer, musician and vocalist – to our music. Badaruz-Zaman has this uncanny feeling that the stature of Tansen is not fully acknowledged, as he is portrayed mainly as a vocalist, while his contributions to the making of raga, and his theoretical understanding that flows from it is set aside, as he had not written a granth or sangeet. However, according to Badaruz-Zaman he wrote Sangeet Saar and Ragamala. In referring to the works that are ascribed to Tansen, Zaman was reproducing various dohas that showcase his wisdom and an intuitive understanding of music. Dhoha, mantar, shalok and shabd were a common method of encapsulating knowledge in a versified form in our tradition.

Zaman talks in great details about many of the ragas that are not frequently sung or played - but are seen as the preserve of great ustads who have the virtuosity to fully negotiate the complexities involved. He mentions 56 of them - with their ascent, descent, catch phrases, manner or expansion, compositions - some traditional, some of his own creation with the nom’d plume; rub rung. Many of the ragas in practice today, are difficult to trace to their origins, while many have resurfaced with different names or have been mentioned with other nomenclatures in authentic older texts. Many unsung ragas today, have gone out of fashion either because they are too complex, or the traditional method of singing a raga has been replaced by short compositional pieces, where priority is given to lyrics rather than the musical mode itself.

Also, many ragas are sung differently today from the way they are mentioned in older texts. There are also cases of a raga having more than one thaats (tunes) it is sung or remembered by. The surs and their musical movements have varied through the history and geography of our musical heritage. Zaman has very responsibly pointed to various ragas, in various thaats, with varying prescribed movements rather than being definitive or rejecting one in favour of the other.

Since our musical history has existed in the oral realm, many of its stages are undocumented. There are dark areas, some of which allow easy explanations. Moreover, the modern-day development of music and current contexts of what musicologists have modified, tampered with and rearranged must be taken into account. History, across its spectrum can only be viewed in light of the present. We must analyse the present configuration of our musical forms which mostly took place in the colonial era; antiquity on one side and our colonial masters on the other, all set against the backdrop of the struggle for independence in the sub-continent.

Surmandal Ustad Badaruz-Zaman Idara-e-Faroghe-Fun-e-Mausiqi

Pages 319

Price Rs999