It comes as no surprise to see popular Urdu fiction portraying widows or divorced women as objects of pity

No matter how diverse the reading may be, readers somehow end up rereading about experiences that relate to their current stage in life. But in all our reading journeys there comes a moment when certain stories, certain poems just come our way, making us vicariously experience what life had hitherto eluded. Such has been my experience with literature representing widows, divorced or separated women.

For a society that defines a woman’s existence in reference to a man, be it a father, son, or - the honour of all honours - a husband, it comes as no surprise to see popular Urdu fiction specifically of the digest variety portraying widows, divorced or separated women as objects of pity in the best case scenario or a man-eater in the worst. In case of widows, stories like Abstraction deal with the emotional trauma of a life that society expects them to lead alone, and the very physical nature of desire that they now need to curb for the rest of their life, which Neelofar Syed terms as a metaphorical satti (Wo Wasal Kahan) or Sylvia Plath’s description of widow’s existence as a "broken, vacant estate" or "a shadow thing" (Widow) exist in English literature. But literature in general has focused more on the economic plight and social stigma due to the absence of the ‘man of the house’ than on the psychological consequences on a woman’s sense of being widowed or divorced. Rarer still is the scenario where the death of a husband may come as a relief. In the case of Mrs Mallard (Story of an Hour) who upon realising the implications of Mr Mallard’s death can’t help but wonder, "Free, free, free! … Body and soul free!"

Some may say this is because of the differing cultural norms at play here but as contemporary Pakistani women become more financially independent, thereby eliminating one of the key factors that affect a woman’s choices, doesn’t relief become as normal a response as grief and mourning?

In contrast, when it comes to the representation of divorced or separated women in English literature, we sense a somewhat celebratory attitude in both popular and literary fiction, especially memoirs. This comes as no surprise, as English literature with the exception of romances and chick-lit generally does seem to favour an anti marriage, anti commitment stance despite its insistence on finding a soul mate. Be it Clarissa Dalloway or Emma Bovary we see protagonist after protagonist trapped in an unexciting married life, thereby questioning the very need of such a union.

Also read: Editorial

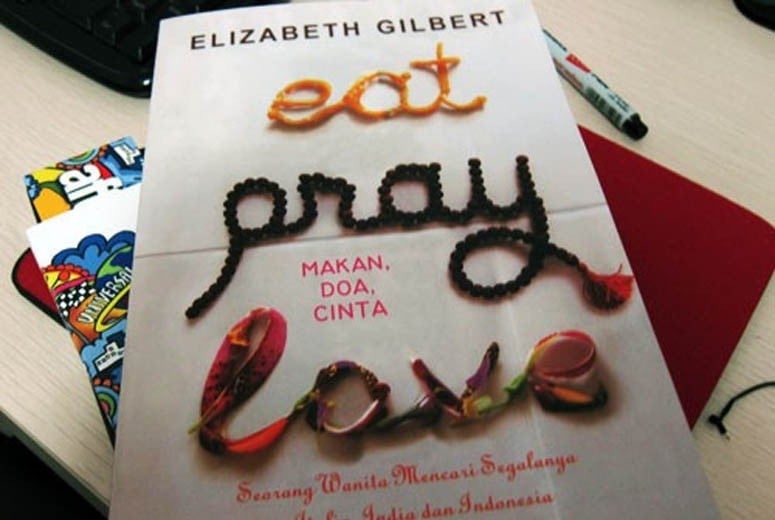

However, it is in contemporary writings, especially memoirs that we see a certain sense of celebration of the independence, self reliance and most importantly self awareness that divorce brings. Despite the contrast in the depiction of the post-divorce, post-separation life, works like Eat, Pray, Love (Elizabeth Gilbert) and Wild (Cheryl Strayed) use the journey narrative structure to portray the self discovery process that is triggered by divorce and in doing so, at times even glamorise it to an extent that it may appear unrelatable to the lived experience of real women in these circumstances. One could attribute this shift to the growing divorce rates, financial independence and access to legal rights to women in the West. However, isn’t it time that a similar shift occurs in contemporary local narratives too? As women here reclaim their agency, as evidenced by cultural phenomena such as the Aurat March, and the emergence of support groups and services, often led by women going through a similar situation themselves, shouldn’t our literature step up to represent these narratives too? The narratives that bring hope?