Interview of Zakir Thaver and Omar Vandal, producers of the documentary Salam - The First ****** Nobel Laureate

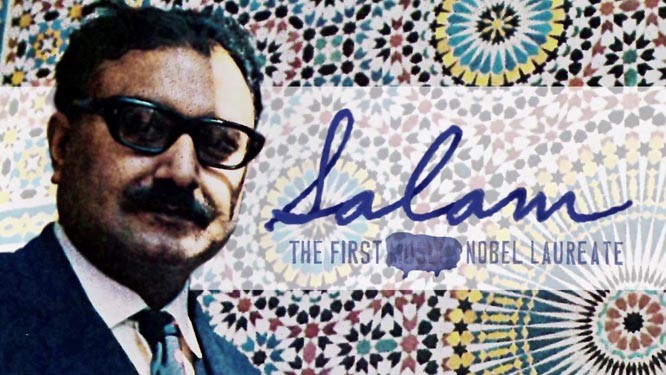

Salam – The First ****** Nobel Laureate, filmmakers Zakir Thaver and Omar Vandal’s labour of love, tells the untold story of Pakistan’s most illustrious scientist Abdus Salam. The documentary, originally released in 2018, became accessible in Pakistan only after it was released on Netflix in October this year. In a little over an hour, it manages to highlight some of the defining aspects of the Nobel laureate’s remarkable life, including his unfaltering dedication to his work, his faith and his nationality.

In a recent email interview with The News on Sunday, Zakir Thaver and Omar Vandal talk about the challenges they faced while filming the documentary, some of the most memorable moments during the effort and how Salam continues to inspire people all around the world. Excerpts follow:

The News on Sunday (TNS): This project took 14 years to complete. Tell us about the process, the effort that went in, and some of the challenges that you faced along the way. Did you ever feel like quitting?

Zakir Thaver/ Omar Vandal (ZT/OV): As soon as the first person donated for the project (a wonderful lady from Lahore) we felt compelled to see the film all the way to completion. We saw [our accepting the donation] as entering into an implicit contract; that we would use her money well and see the project to fruition. Around the time we discovered Salam in college, in 1996 and had decided at some level to tell the story, we also saw Apollo 13 (1995). We were moved by Gene Kranz’s dictum, "failure is not an option". When we formally embarked on the project, we’d constantly remind ourselves of his resolve.

We loved and believed in what we were doing and never thought about giving up, despite the many -- largely fundraising-related -- frustrations. Delightful emails from students from all over the globe would light a spark. They would typically send in small donations and write encouraging notes. These were unexpected, timely shots in the arm, as it were, and kept us at it through the years. We ended up with 400+ donors, we like to think of the film as the people’s outcome on Salam.

TNS: One hears that you collected archives on Salam from all over the world. Tell us a bit about what it was like.

ZT/OV: This was arguably even more challenging than the fundraising. The internet wasn’t the place it is today. Libraries didn’t have the kind of query-able catalogues they have these days. We read everything on Salam, by Salam and even remotely about Salam. We found out where he’d been around the world and given talks or appeared on TV and radio. It was a whole lot of chasing down and phone calls to people all over the globe. There were many dead ends of course, and some material never made it to the film.

But there were also certain amazing successes. Each piece of the archive has a story. For instance, Pervez Hoodbhoy had interviewed Salam on his PTV programme Rastay Ilm Kay in 1989. The PTV had lost their copy. For 10 years, we kept pestering Hoodbhoy to look for his copy. Unbelievably, he found the VHS tape. It sat under a pile of books for years - a terrible way to store any piece of the archive - but miraculously it was in great condition.

A lot of people who claimed it had been too long since they’d recorded Salam and thought it near impossible to be able to find the recordings, did eventually end up finding them.

In the last three years of the project, we brought on board a Brooklyn-based filmmaker, Anand Kamalakar, to direct/edit the film. In our edit room discussions, we realised we needed to tell Pakistan’s story more comprehensively in parallel to Salam’s, thereby, expanding the scope of the archives we’d need, by manifold. We now needed archives on Zulfikar Ali Bhutto and Ziaul Haq. By then we’d become quite adept at finding archives and knew where to look. Library catalogues were now online and they could be queried. We kept getting better and better at it and managed to find historical archives for the various locations featured in the film: Jhang from the 1950s, Trieste from mid-1965, Lahore from 1949. All rare. Salam’s family also had amazing archives and we spent many days at their homes looking through notebooks, photo albums, videotapes, that they very graciously shared with us.

TNS: Can you share some interesting insights that developed during your research?

ZT/OV: At some point, it occurred to us that Western loggers unfamiliar with the name ‘Abdus Salam’ might have misspelt him as, ‘Adbus Salam’ or ‘Abdul Salam’. Some might have misspelt Salam as ‘Salaam’. So we searched all of these misspellings and found some amazing bytes.

People who’d told Salam’s story before us in other formats had archival material they were more than happy to share with us. If you look at the number of people and entities acknowledged in the film’s end credits under archives, it’s a long list. The last piece of Salam archive that we found was a rare interview he’d given to the Korean Broadcasting Service in the mid-eighties. We’d given up on it, but a Canadian-Korean friend offered to find it for us and weeks later handed it to us. Her father in Korea had contacted people he knew at the network who then dug it up. When you put in an obscene amount of work into anything and well-meaning people see you do it, they’ll come to your aid.

TNS: The documentary primarily shows how the great scientist was shunned in a country that he loved. Was this how it was originally conceptualised or did it take this shape gradually?

ZT/OV: Both of us discovered Salam via our love for science. We always wanted to tell Salam’s story to inspire Pakistani youth to pursue science. Both of us have also worked to enhance the public awareness of science in Pakistan. It was a very difficult decision for us to remove the science explanations from the film -- which was initially conceived as a documentary in which we’d certainly explain the science. Ultimately we felt it wasn’t accessible or lay person-friendly enough, and the film was very ‘rich’ as it is.

TNS: But don’t you think that more of Salam’s work should’ve been discussed in the documentary as well? Since not many in Pakistan are familiar with his groundbreaking contributions to science.

ZT/OV: Salam et al used the Higgs mechanism in 1967-1968 to unify the electromagnetic and weak nuclear forces. When the Higgs boson was finally discovered in 2012, there was a lot in the press then about just how difficult it was to explain the “God particle" to a lay audience. To successfully explain the electroweak unification (Nobel prize 1979), we’d also have to explain the Higgs mechanism (Nobel prize 2013). That’s two pieces of Nobel prize winning physics. Doubly esoteric. With the science included in an earlier iteration of the film, we found our audiences in focus groups we ran were losing interest.

We did interview two brilliant science communicators, celebrity physicist Brian Greene and Jim Al Khalili. However, the rest of the film had "characters" who had only one degree of separation from Salam, i.e. son, student, colleague, wife, secretary etc. And that’s what kept it intimate. With unrelated science communicators, however brilliant, we might have lost this emotional intimacy and/or the connection the audience develops with the characters. We then experimented with Salam himself explaining the science, but this too wasn’t entirely layperson friendly.

We plan to release the science explanation we edited-out as ‘deleted scenes’ on our film’s social media channels. We’re working on polishing it and will release it soon. It’s being put together using rare archives and original animation. We’re also raising funds to create a 30-40 minute science version in which we’ll pair Salam’s efforts to make science accessible to the world with Salam’s science itself.

TNS: What were some of the difficulties that you came across in trying to make the documentary accessible in Pakistan?

ZT/OV: The bulk of our screenings in Pakistan were closed-door. We knew we wouldn’t be able to play it in cinemas given the sensitivity of the subject matter. Two prior attempts to document Salam’s life for TV were sabotaged (content was deleted and a poor quality version aired) or thwarted (was made but kept from airing). So it had to be a streaming platform. We knew this very early on and kept thinking of how to make the film accessible in Pakistan. In 2012, we noticed how well Jerry Seinfeld’s online series Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee worked even on average-speed internet connections in Pakistan. We felt even more strongly that online streaming was the way to do it. Of course, Netflix has amazing reach and works even better on poorer connections still, so we were absolutely thrilled to make our film available in Pakistan via Netflix, the world’s largest streaming platform.

TNS: Do you think that with the advent of streaming platforms, making films on subjects that are taboo in this part of the world might become a bit easier?

ZT/OV: The reception has been overwhelming. It’s showing up in ‘Popular on Netflix’ in Pakistan and ‘Trending’ in the Uk -- and counting. Streaming platforms will certainly make bringing taboo topics to the fore easier. However, people have got to stop pirating films that take years and years to make. One hears Pakistani audiences complain about ‘not enough Pakistani content on Netflix’ but when there finally is content, there are attempts to subvert the very portal that has just empowered Pakistani filmmakers. It’s biting the hand that feeds you. Pakistan has a unique chance of showcasing its work on the global stage via streaming platforms. Yet there’s a high rate of piracy and we will end up sabotaging precisely the high-end originals from Pakistan we like to consume. Producing for streaming media platforms is effectively an export. And Pakistan is better in the episodic format that’s popular on Netflix than India, we think. Our dramas are hugely popular in the subcontinent. Audiences should support the platform that features content they resonate with.

TNS: What were some of the moments that moved you the most during your research on Salam?

ZT/OV: There were many many. Every day working on the film was full of adventure and we would regularly stumble on the unexpected. Let us share what’s more current: interacting with people who saw the film at festivals. We were very moved when these two men came up to us after we screened the film in Washington, DC, and told us they were present at Salam’s funeral. They felt exactly how Salam’s wife said she’d like to believe they did, "yes, I was there when they welcomed Abdus Salam home." They told us they had goosebumps when they saw the film. They had us play the film again and pointed out where they were in the 1996 archival footage.

This other lady who saw the film in Chicago told us her father had passed away in the twin attacks in Lahore in 2010. She told us how it made it viscerally real for her. One really begins to appreciate the impact of one’s work when one sees how it affects people.

At our screening at the MIT, we walked into their state of the art screening room with our MIT-alumnus executive producer and it was empty. Hearts sank. We wondered if people would even come. Then these two students walked in. They were NYU students who had driven from New York just to see the film. In thirty minutes from then, the auditorium was fully packed. This we’ve seen happen repeatedly and globally - in Paris, Nijmegen, London, Chicago, Colombo, Islamabad, Lahore, Boston, DC, Seattle and New York, among other cities. It’s incredibly moving.

We’re also learning about Pakistani students who are taking it upon themselves to screen the film at their universities. This is incredible. When students take on something, bypassing the old guard, that is when you know you’ve dented the zeitgeist, however humbly. As Salam says in the film "whenever you have a good idea, don’t send it for approval to a big man."