The withdrawal of a cartoon by a daily newspaper is a bad compromise on the message -- for "against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand"

Khalid Hussain’s latest cartoon printed in a daily newspaper that depicted Prime Minister Imran Khan pulling a chariot, Modi and Trump aboard, holding hands while offering a carrot to Khan, has raised questions about the place of satire in Pakistan. The carrot, dangling from the end of the hook of a fishing rod, it suggested, was meant to entice Khan to move faster… and faster. The mediation offer was a bait, it said.

Reacting to the outrage over the image from authorities that be, the newspaper issued an apology and suspended its contract with Hussain. How could the PM be shown on all fours at such a crucial time in Pakistan’s history?

As a wise man one said, humans are the only species that laugh. They laugh, it has been suggested, to forget about the death perpetually staring at them. Cartooning is not a positive art. It’s essentially negative, and relies on ridicule and sarcasm. It also carries hidden messages. Its success is seen in laughter it may induce. Obviously, that sense of humour is missing around us.

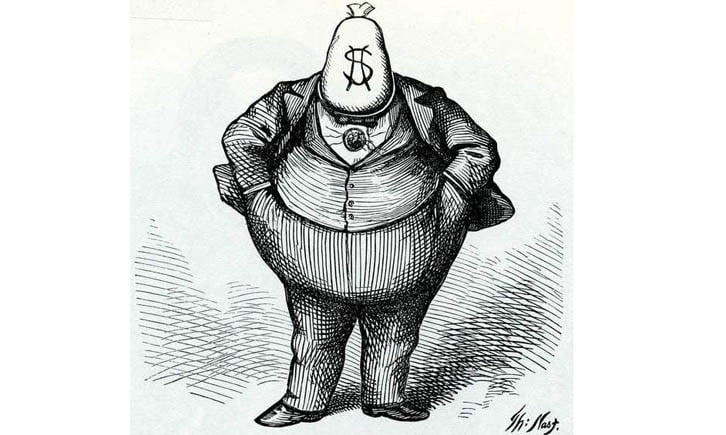

Thomas Nast, the father of modern cartoons, was responsible for bringing down ‘Boss’ Tweed, the notoriously corrupt politician of New York City. His images were so effective that Tweed blamed Nast’s pictures for his decline. "I don’t care a straw for your newspaper articles; my constituents don’t know how to read, but they can’t help seeing the damned pictures," said Tweed.

I remember joking with my editors, telling them their editorials are read probably by a mere 35 percent of their readers whereas my cartoons are seen by 100 percent of them. Satirical images send out strong messages in a country where literacy rates are low, they are even more effective. Pakistan has one of the lowest literacy rates in the world. It also has almost 22.8 million children out of school. In such a setting, images communicate across levels of education and linguistic boundaries.

Dictators and kings like to portray themselves as larger-than-life, as mini gods on earth. Cartoons cut them to size. They depict them as fallible, ordinary mortals. They challenge the egos of the powerful. In this sense, cartoons are a by-product of democracy. They represent citizens’ right to criticise their leaders.

The advent of the printing press enabled the distribution of cartoons. In the West it became a powerful weapon to bring down monarchies. It also became the voice of people ruled under the divine right of kings. The history of the idea can be traced back to the city-state of Athens, where comedians satirised their leaders. They even mocked Socrates.

In more recent times, look at how Steve Bell illustrated George W Bush and how Steve Sack depicted Trump.

A few months ago, the New York Times, published a cartoon by Portuguese cartoonist António Moreira Antunes that depicted Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu as a guide dog leading a blind Donald Trump. Due to the outcry, condemning the cartoon’s ‘anti-semitic’ imagery, the paper decided to discontinue political cartoons in its international edition.

In a similar act, Canadian cartoonist Micheal De Adder lost his job for showing Trump playing golf over dead bodies of two drowned immigrants.

Cartoonist Musa Kart, a former journalist associated with Turkey’s oldest newspaper, Cumhuriyet (established in 1927), along with 14 others, was jailed for ‘supporting, terrorist organisations.’ Kart was released from jail this year. Some of his co-workers are still in jail. Famous Malaysian cartoonist Zunar faced 43 years in prison over drawings and tweets criticising then PM Najib Razzak.

So, intolerance towards cartoons is not just limited to Pakistan. It’s all over the world. The freedom of press index is predicting a decline in editorial cartoons.

A pertinent question is if the decline in freedom of cartoons is related to the decline in democracies. It is quite apparent that intolerance is stifling free voices in countries with populist governments or one-party governments or monarchies.

Some of our leaders can be quite blind to the larger picture. They don’t recognize that being a subject of cartoon is a privilege - for only people whose actions and words impact the lives of others are caricatured by cartoonists. In developed democracies, retiring politicians expect to be presented collections of cartoons as souvenirs to remind them of their career at its peak.

In Pakistan, while the number of columnists may run into hundreds, the number of satirical cartoonists is small. One can count them on fingertips - mainly because of the intolerance for satire. Also, satirical imagery is a difficult form. To be a satirist or a cartoonist, one needs command over the medium, like the great Mushtaq Ahmad Yousafi. Indian cartoonist, RK Laxman has said, three things are necessary for a cartoonist, drawing like a master craftsman, voracious reading and a sense of humour. Although one can spot occasional comedians on TV, their work is mostly non-political. They rely on stereotypes targeting mostly women and transvestites.

Realising the threat to satire in Pakistan, some Pakistani cartoonists got together recently to form the Pakistan Union of Cartoonists. Their aim is to enhance the understanding of cartoons as a medium and promote and defend the art in Pakistan.

The withdrawal of Khalid Hussain’s cartoon is a bad compromise on the message. But, as Mark Twain said, "Against the assault of laughter, nothing can stand."