Political leaders can no longer ignore the demographic question

At a time when Pakistan continues to face political and economic challenges, demographic issues are coming to the fore. Such a volatile combination risks turning the country into one of the world’s most difficult to govern.

This has been compounded by the fact that since Pakistan came into being in 1947, governments have tended to keep the British legacy intact by undertaking no serious efforts to restructure administrative units in line with a changing geo-political landscape.

The colonial masters had adopted policies amenable to continuing their repressive rule, which saw indigenous populations deprived of basic human and political rights. Meanwhile, local chieftains became de facto leaders and were hostile to reforming these administrative units.

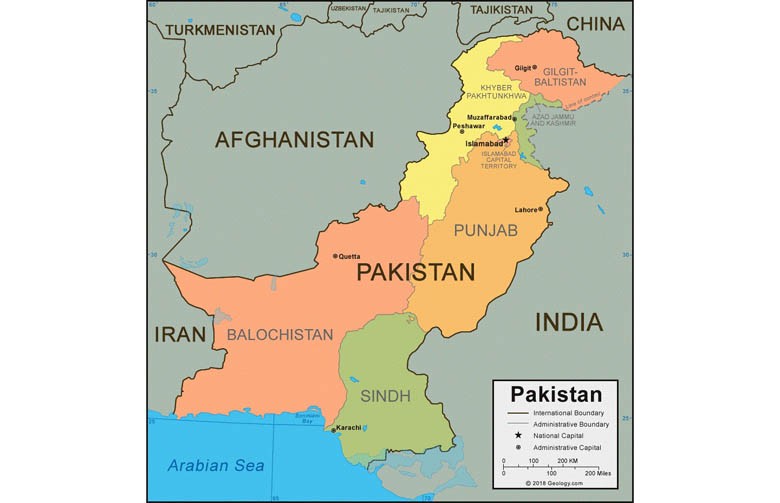

The Punjab accounts for 25.8 percent of the country’s landmass but is home to 60 percent of the population. By stark contrast, Balochistan is the largest of Pakistan’s provinces. It covers 42 percent of the country but is home to just 6 percent of the population. The Federally Administered Tribal Areas (FATA), spanning some 27,000 km, before the recent merger with Khyber Pakhtunkhwa (KP),were left to their own devices. For more than 70 years, the people were denied fundamental rights in the name of autonomy. The consequences of this included lack of access to basic amenities such as health and education. The region suffered from lack of development in terms of infrastructure and trade; turning it into a lawless area at the mercy of arms smugglers, drug mafias, kidnappers and worse. In addition, the 1965 Afghan Transit Trade (ATT) ultimately damaged the local economy since goods meant for Kabul were regularly smuggled back to Pakistan; meaning a high opportunity cost in lost tax revenue.

Gilgit-Baltistan (GB), formerly the Northern Areas - covering over 73,000 km with a population of around 2 million - has also suffered at the hands of mal-administration. Bordering the restive Chinese region of Xinjiang, in the north and -held Kashmir in the east, there is no denying GB’s strategic location. An international dimension is also at play now that the ambitious China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) passes through this territory. Azad Kashmir lays claim to the area but Islamabad has stalled on affording the local population the right to self-determination. The upshot being that the people continue to be denied their political rights.

Karachi, traditionally a geographical part of Sindh, had been accorded a special status after it was crowned the capital of the new state of Pakistan. Upon its subsequent ‘demotion’, the city was once more merged into Sindh province. Had this not happened - Hyderabad would have become the provincial capital and, thus, a business and commercial hub. As things stand, the rise of ethnic politics and violence has rendered Karachi largely dysfunctional for those who live there. Indeed, it is now one of the world’s most unliveable cities.

Balochistan, for its part, still maintained the status of colonial agency until 1970, when President Yahya Khan abolished the One Unit and unilaterally declared it Pakistan’s fourth province. In many ways, Balochistan has a heterogeneous make-up as it is home to different ethnicities and cultures. Its unique composition on the landmass and population fronts means that it has represented challenges for successive governments, including the very unity of the country. Problems of governance - fanned by political conflict and ethnic tensions - have adversely affected prosperity. As a result, Balochistan is the least developed of all Pakistan’s provinces despite being rich in mineral resources.

Another victim of misplaced non-pragmatism is the Gwardar enclave, which had belonged to the Sultanate of Muscat and Oman for 174 years until Pakistan acquired it in 1958, during President Ayub Khan’s tenure. It was then incorporated into Balochistan. The port now falls under the CPEC ambit. This has fuelled speculation that certain powers - both friends and foe -are actively trying to thwart the port city’s transformation into a regional trade hub.

While voices have been intermittently raised against the current division of provinces and territories - the country’s political woes will not be eliminated by continuing down this path. What is needed is good governance. And this can only be delivered if administrative units are restructured. Elsewhere, constituency politics is another colonial overhang, which deprives the majority of their voice in Parliament while also promoting horse-trading.

Those at the helm should take note. For Bilawal Bhutto Zardari is right when he denounces moves to invoke Article 149 to hand over control of Karachi to the Centre as a conspiracy against Sindh. The only way forward is to abolish the provinces and empower local governments at the district level. But for this to happen, the political elite will have to refrain from issuing partisan warnings and threats.