Around the time of the Partition, children’s literature was progressive, senior literary figures were writing for children and thinking about them. Today, there is a void

When my girls were young, I was not too concerned about the books they spent hours reading; I was content as long as they were reading something. Looking back though, perhaps I should have taken more interest in the matter. I now know that literature has the power to influence children from the day they come into contact with it - what they read eventually shapes them as individuals. I have also come to the realisation that all literature is more or less political. The fact that the princesses of our age-old fables exist solely in order to meet their Prince Charming someday is in itself as political a message as the mention of issues such as environmental justice and civil rights in children’s books like A is for Activist.

Politically-committed or progressive literature for children attacks or defends particular positions through subtle undertones. It can be leftist, anarchist, or reactionary in its stance, among many other standings. Jean-Paul Sartre believed that committed literature involves a free writer and a free reader. By reading a book, you, alongside the author, take on the responsibility to transform the world. By virtue of which, a good novel must push the reader to act towards the development of society as a whole.

Going by that logic, however, a popular book that gives out subtle messages of intolerance or religious extremism should be perfectly capable of wreaking havoc on a society.

So what happens when the reader is a child who lives in a country like Pakistan, where arguably most of the locally-produced literature for children has been methodically radicalised over the years?

More importantly, how did we get here?

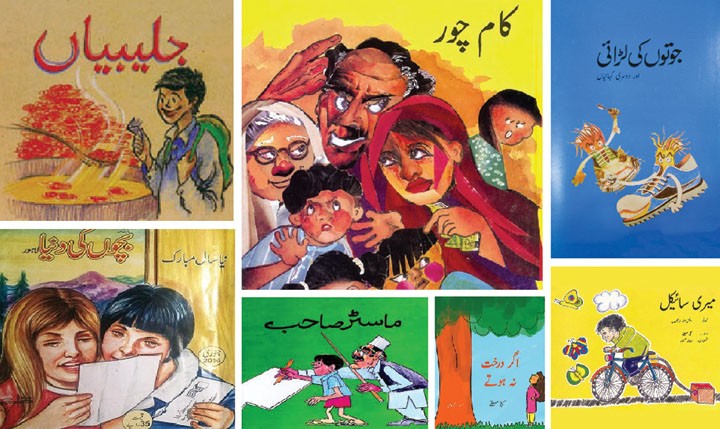

"Things [regarding children’s literature] were not always like this," says writer and literary critic Nasir Abbas Nayyar. "Before partition and immediately after it, all senior Urdu writers like Mirza Adeeb, Qurat-ul-ain Hyder, Imtiaz Ali Taj, Muhammadi Begum, Soofi Tabassum, Intezar Hussain, Kishawar Naheed, etc, wrote literary content for children as well. Children’s literature was progressive back in those days. Right now, none of our senior literary figures writes for children, leaving a void."

Nayyar asserts that the presence of such a void gives rise to opportunities for negative elements to take hold - hence the gradual radicalisation of children’s literature in Pakistan. "Major responsibility to produce meaningful literature lies with senior authors. When good writers stop writing for children, that void will naturally be filled in by people with ulterior motives, for example, religious extremists in Pakistan’s case. Children are then at the risk of being exposed to extremist ideology through literature from an early age."

Nayyar says, the situation regarding children’s literature is dire. "When Imtiaz Ali Taj and Muhammadi Begum initially began the publication of Phool (a children’s magazine), many renowned writers used to write for it. Same was the case with Taleem-o-Tarbiat [another publication for children’s]. It is not the same anymore." He says that the content in Urdu magazines for children is now riddled with extremist ideologies. "No renowned writer writes for them. And there is no discussion about this matter in literary circles."

Nayyar suggests that a conscious effort needs to be made by authors and publishers alike to gradually re-integrate progressive/secular elements into our children’s books. "This process can be started with the publication of age-appropriate versions of our classical literature, for kids."

Children’s author, activist, and graphic designer Innosanto Nagara says that the more ‘globalised’ media our kids consume, the more important it is that we have alternatives to the dominant [state] narrative.

"A broad definition of diversity, cooperation, and the common good--and seeing one’s place as an actor, not an observer, in the march of history--are values that even the youngest amongst us can explore,’’ says Nagara, who is also the author of the worldwide bestselling alphabet book A is for Activist.

Writer and critic Haroon Khalid asserts that production of literature that promotes a sense of harmony and acceptance amongst children, is now a necessity. "Small touches, like a non-Muslim friend mentioned in a thrilling, imaginative children’s adventure, can convey our message effectively," he says.

When a book is suggesting best ways for a child to make the world a better place; isn’t that, too, slightly akin to ‘indoctrinating’ the malleable young mind? According to some critics, conveying messages of goodwill to children can be as worrying as the tales that silently cultivate assent to social inequality and religious extremism in their impressionable minds.

"Generally, I am against any kind of agenda-based writings, as literature must be honest and free," says Khalid. "But given the damage inflicted on children’s literature over the past few decades and the flawed value system that we have erected in our society, a subtle balancing is in order, i.e., a tilt towards tolerance and pluralism without curbing imaginations."

Book critic Moazzam Sheikh is of the view that children, by and large, are progressive beings by nature. "They absorb political information, and state’s/or society’s biases via various sources such as media, family and their social environment. By the time a child has grown up to be a young adult, their mind has processed a lot of information -- along with false information about history."

He says that due to this reason most countries appreciate nurturing a parallel literary sphere, where these young minds can eventually develop the ability to think on their own. "However, in countries like Pakistan, where the literary culture is weak, political thinking lacks nuance."

It is not that Pakistani writers are not producing commendable children’s literature at all. Some recent examples are books by Fauzia Minahalla Bano, Billoo and Amai and Amai and the Banyan Tree, P is for Pakistan (an alphabet book) by Shazia Razzak (p.2007), The Magical Woods by Saman Shamsie (p.2014), King for a Day by Rukhsana Khan (p. 2014), which are all set in Pakistan. There are many others too.

But given the ever-increasing religious conservatism in Pakistan, how will Pakistani authors and publishers manage to produce literature that would address issues like religious harmony, multiculturalism, civil/social rights, eco-socialism, feminism among others?

"I think people of Pakistan have become very vocal in recent years," says Awais Khan, who is a writer and conducts regular writing workshops for adults and children. "With the advent of social media, raising awareness and using these avenues to bring forth meaningful literature for children, that celebrates diversity and togetherness while discouraging discrimination, is now relatively easier than it was ever before. It’s just a question of investing the time and resources into making this happen," he says.

Khalid says that authors can focus on the broadening of children’s horizons by producing quality fantasy or adventure literature. "In this endeavour, if we can break shackles of stereotypes by undoing years of damage towards understanding fellow humans, it will be handy. But rather than it being an obsessive agenda, this should just be a considerate thought to be planted scarcely somewhere in the story. If it is imposed at the cost of imagination, it must be culled. Let genuine literature win."

"Between an idea and its existence in the literature that is in the hands of a child, there are many gatekeepers; the author, agent, publisher, parents, book stores etc," says Nagara. "The willingness of each of those gatekeepers to have the courage to take the risk and take the idea to the next step is what ultimately makes a difference. People don’t operate in a vacuum. Movements drive change. I have seen the movement for more meaningful children’s literature grow since the publication of A is for Activist. I am hopeful that this can work anywhere in the world," he says.

We can argue that children are not completely free to do whatever they please, as they are dependent upon adults to carry their day to day tasks. Nonetheless, committed literature for children exists all around the world. Because despite the general conservatism of society, adults, somewhere deep down inside, still believe that children are freer than them to make their own decisions. The availability of progressive literature serves as a subtle declaration by adults that the children of today are capable of transforming the future they will live in.