Why has great drama not been written in the subcontinent? The answers are many, intriguing too

A distinction must be made between drama and the dramatic narrative. There have been very few places in the world where drama, as a form of art, has thrived. Among them are Greece and the Indian subcontinent. In almost all other parts, the main thrust of a performance has revolved around certain caveats called the dramatic narrative.

Actually, in most parts of the world, the dramatic narrative has taken over drama. It is considered safe because the role of the narrator is overwhelming. The narrator controls the action or keeps it on the appointed course. The apprehension with drama is that it assumes a life all its own, giving way to interpretations that may be difficult to undermine or seen to be insidious to the intent itself.

While in Greece theatre died, and only a watered down form of it survived during the Roman Empire, in the subcontinent it was inundated by its transformation into religious rituals. Many of the western historians and critics have given the credit for the beginnings of drama in the subcontinent to the Greek invasion and the stretching of its rule over hundred to two hundred years. They say that it liberated drama from the clutches of mythology and subsequently treatises like the Natya Shastra were written on the rules of dramaturgy.

This is an unending debate where the extra variables like political power and soft influences weigh in more than the veracity of facts.

In our part of the world, the dramatic narrative was rendered in the form of qissas, dastaans and kathas. The narrator was or is primarily one person, who narrated the story. In the course of that narration, he assumed roles of various characters. He had great facility with the text or he had a memory that was sharpened to retain vast amounts of material with the ability to move from one role to the next, while as a narrator also holding on to the basic thread of the tale.

It was only after renaissance in Europe when the Europeans decided to model their civilisation on the lines of the classical one, namely the Greeks, that the revival of drama took shape. It produced in the process great works and great playwrights.

The tradition has continued to prosper in the western world with varying degree of success. In the subcontinent, however, it was given a kiss of life through its colonial encounter, and drama emerged with good deal of qualification.

The same tradition transferred to the screen in the 20th century. The great success of the Indian cinema has been a consequence of that.

After the gradual demise of the Sanskrit theatre, many aspects of theatre were incorporated into religious ritual. For centuries, Ram Lila and Ras Lila quenched the thirst for theatre through the high dramatics of the enactment of tales or episodes from religious mythology.

In the Muslim world, there has been a problem with presenting religious figures on stage. Actually, even the pictorial representation has been shrouded in great controversy.

In our poetry, which then blossomed into Urdu, marsiya evolved as a form after Aurangzeb’s almost 30 years of continuous presence in Deccan, trying to conquer the Bijapur and Golconda states as well as the Marathas. When his armies returned to the north, they were imbued in the cultural traditions of Deccan. Urdu, meanwhile, had been graduating from a dialect to a language. Wali Dakhani, the first major poet of the language, was from the same area.

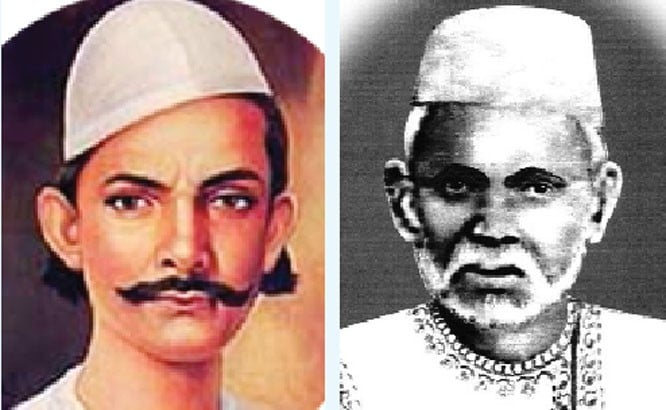

Consequently, the dramatic narrative developed a great deal in Awadh. Marsiya had been recited but Mir Zamir used a popular spoken rhythm called tahtul lafz. Gradually, marsiya in tahtul lafz replaced the traditional majalis -- Rawzatush Shuhada and Dah Majlis. Mir Zamir’s contemporary, Mir Hasan’s talented son, Mir Mustahsan Khaliq, had inherited his father’s capacity to vividly versify subtle emotions. He made his mark on the basis of linguistic artistry. The characteristics of marsiya created by Mir Zamir were perfected by Mir Khaliq’s son, Mir Babar Ali Anis, and Mir Zamir’s disciple, Salamat Ali Dabir. Both were the precursors of the modern Urdu poetry in the following century.

With the passage of time soz- and marsiya-khawans, instead of reciting their own verses, took to the texts of Anis and Dabir, and became specialists of sorts. Urban culture as it has evolved in the last two centuries is represented by such a prototype.

It is likely that Mir Anis was exposed to the theatre. He may have borrowed aspects or parts of it. Still he did not aspire to write a play on the tragedy of Karbala, building on the elements of the dramatic narrative form embedded especially in the masnawi and musaddas poems. He did not travel much either, probably only journeyed to Azeemabad and Hyderabad Deccan. It is not known whether he went to any of the growing port cities, where a more polyglot culture was taking shape under the patronage not of the royalty but the new mercantile class.

The question has often been raised as to why great drama has not been written here. The answers are many and some of those are quite intriguing. According to Iqbal, drama could not be written because it embodied a process of depersonalization, while the emphasis in our traditional heritage had been on the empowerment of the person. Iqbal himself was not favourably disposed towards drama because he thought that it did not let the writer or the protagonist retain his singular integrity. The greatest quality in a playwright, "negative capability" in the eyes of Keats, was a disqualification in the eyes of Iqbal.