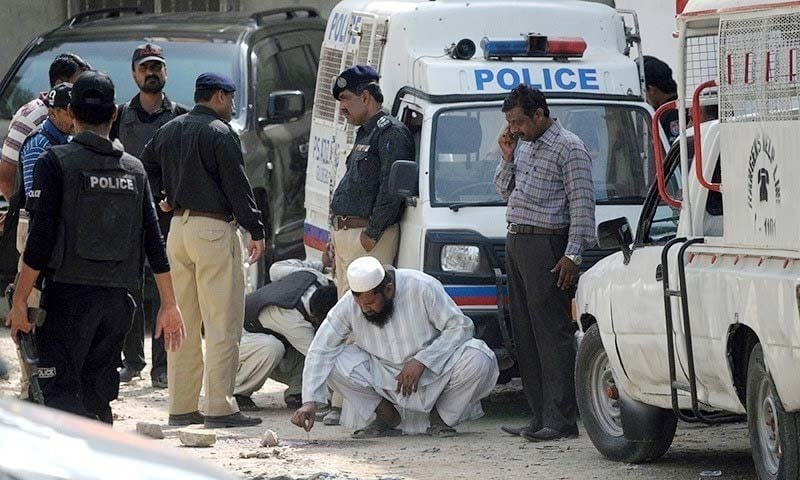

Police officials present on a mob lynching scene often hesitate to intervene

Lynching of suspected criminals at the hands of crowds, big and small, has lately become too frequent an occurrence in Pakistan for comfort. It is often assumed that these incidents involve random and mostly spontaneous regrettable acts of violence, yet sometimes these incidents are purposeful, provocative and deliberate acts of violence.

Mob lynching is no ordinary crime. Experts say investigating murders committed by unruly mobs is nothing short of solving a complicated puzzle. Inefficient police response, inaccurate methods of collecting evidence and an ineffective criminal justice system are some of the main reasons why most of the times perpetrators escape punishment, experts say.

Police and public order are state subjects. Governments are, therefore, responsible for maintaining law and order, and for protecting the life and property of citizens. They are empowered to enact and enforce laws to curb crime in their jurisdiction.

Nevertheless, it is often observed that despite being at a mob lynching, police officials hesitate to respond. In 2015, following a deadly bomb blast in Youhanabad Lahore, two motorcyclists were murdered and their bodies were put on fire by a mob which suspected them of being accomplices of the terrorists who carried out the bombing.

Depending upon the criminal offence, various sections of the Pakistan Penal Code (PPC) 1860 are included in the first information reports (FIR) in such incidents, including Section 148 (rioting armed with deadly weapon), Section 149 (which applies to every member of unlawful assembly guilty of an offence committed in prosecution of common object), Section 307 (attempt to murder) and 302 (punishment for murder).

It is always a difficult task for police to handle cases of mob lynching, especially when the mob tortures, and eventually kills, a person accused of theft. "The psyche of the police force itself plays a pivotal role here," a station house officer (SHO) tells The News on Sunday on the condition of anonymity. "Most of the times, the police officials present at the site of these crimes do not enforce the law in time because mostly they, consciously or subconsciously, support such treatment of an ‘accused’."

There is another aspect as well. If the mob spares the life of the accused, the police officer says untrained police officials usually take the victim to the police station rather than to a hospital for necessary medical aid. "This attitude sometimes has serious repercussions," he adds.

Reinforcing his point, the police officer recalls an incident which took place a couple of years ago in Narang Mandi, when police recovered an injured man tortured by a mob on suspicion of robbery. The police took him to the police station where he later died. Consequently, the policemen involved were suspended from service and an inquiry was initiated against them after family of the deceased accused the police of custodial torture resulting in death. Later on, they were reinstated when the victim’s family pardoned them after receiving blood money.

On the other hand, Advocate Ansar Shah argues that the police force, in general, is incapable of handling mobs in such incidents, and of collecting sufficient and relevant evidence that could assist during the prosecution.

"Given the capacity of our police force, collection of enough evidence in mob lynching cases almost always seems very difficult. Finding corroboration of the available evidence, too, proves hard," he says. Nowadays, forensics can be of significant help in such cases. Even so prosecutors face great hurdles. "Our complex criminal justice system demands that an eyewitness testify in support of the forensic results. Regrettably, in this process either the prosecution is unable to produce such an eyewitness or the defence makes the examination process controversial," he says.

Often, the witnesses are either illiterate or ignorant of legal proceedings and examination process in court proceedings, he says. That is why, most of the time, the witnesses get confused during cross-examination, especially in the procedure of observing the evidence produced by the investigation team. "If the eyewitness gets confused even for a second it gives the defence room to maneuver," says Shah. In cases relating to matters of religion, no one volunteers to be a witness. That gives leverage to the perpetrators of the crime.

Apart from this, the long lists of nominated (accused) with inaccurate crime descriptions, their roles in the said crimes, and incomplete medical reports make the situation more complex for judges, says former session judge Badar-uz-Zaman Chattha.

"Prosecution has a very important role in such cases. It has the authority to pass the challan submitted by the investigation officer or demand more evidence. However, rather than fulfill the requirements, police produce forged documents or fake eyewitnesses. This ultimately goes in favour of the perpetrators."

In mob lynching cases police typically nominate many people. The law provides that each petitioner can have a separate lawyer. This does nothing but delay the proceeding, he says. In law, on every hearing all the petitioners and their lawyers must be present in the court which does not happen mostly: thus a case may take many years to conclude," explains Chattha.

According to the SHO, sometimes it is easy to point out the accusers [of the deceased] and arrest them. Hate speech that provokes a mob, deliberate acts of violence, or group fights fall in the category. However, to control mobs, and to prove the intention behind lynching remain difficult because of several reasons. "The police are not trained in handling mob violence, group fights, and human rights’ violations. They are not even trained in preserving the evidence. This is a great hurdle in dispensation of justice."

"The inefficient systems of recovering evidence, medico-legal procedure to prove the evidence, the mechanism of proving forensic evidence and the complex process of examination during court proceedings turn the situation in favour of the perpetrators. Thus, there is no doubt that the whole criminal justice system is biased in favour of mob lunching."

Also read: Editorial

Capital City Police Officer BA Nasir admits that the underlying issue behind mob lynching is the lack of public’s trust in the criminal justice system. Though, according to law, the police have to respond in such situations either by use of force or by exercising the authority of arrest, detention and investigation. He says police officials have faced suspensions and have had cases registered against them in certain ‘minor’ incidents, adding that these policies have demoralised officials discouraging them to take initiative, which he says is the core value of efficient supervision.

He says measures should be taken for capacity building and professional training of police officials to ensure operational independence devoid of any interference. "Nevertheless, the reality is that it took 150 years to revise the 1860 Police Act [in 2002]. It still needs to be revised."

"From police to correction services (prisons), the need is to have holistic reforms in the criminal justice system. Therefore, we must consider the lessons learnt in the past and study international best practices to establish a sound criminal justice system," says Nasir.