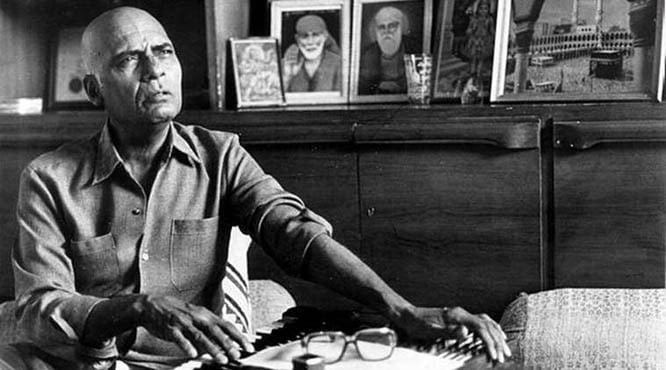

There are very few left in India who enjoyed kinship with Lahore. Music maestro Muhammed Zahur ‘Khayyam’ Hashmi was one of them

It appears that only the wounds of Partition have been left to bleed; with vital arteries duly clogging over time and important connections all but lost. Today, there are very few left in India who enjoyed kinship with Lahore. Muhammed Zahur ‘Khayyam’ Hashmi was one of them. He, too, is no more.

Having spent his formative years in the City of Gardens, Khayyam moved to Bombay, now Mumbai, in search of greener pastures. For even back then, that was the capital of filmmaking in the subcontinent; with Lahore having the role of a provincial outpost. His brothers, Shakoor Bedil and Mushtaq Hashmi, stayed back and attained various degrees of fame. The former was a poet and often recited his verses, mostly hamds and naats. Mushtaq was an amateur singer as well as Government College’s cricket captain. He went on to join Pakistan International Airlines where he held various posts before dying of a broken heart following the death of his son.

Such were the stories in pre-Partition India.

Khayyam began his tutelage in Lahore under Pandit Amarnath of the Indore Gharana and GA Chishti. But even this was insufficient to immunize him against the struggles that he would endure in Bombay. The second generation of film and music greats still ruled the roost at that time. The first generation had comprised the likes of RC Boral, Jhande Khan and Master Ghulam Haider -- among those who took up the mantle were Naushad, Anil Biswas and SD Burman. Only after these left the scene was Khayyam able to truly blossom; with his genius being recognized for decades to come.

He teamed up with songwriter Sahir Ludhianvi, who had also spent his early years in Lahore. The pair went on to compose some memorable numbers. Sahir saw cinema as a means of reaching out to ordinary people from all walks of life. Thus he kept his lyrics simple. Khayyam worked his magic with the music. It was a winning formula.

Film scores in the subcontinent are heavily reliant upon lyrics. Unlike their musical counterparts, which largely go unnoticed, particularly background scores, songs are forever remembered and easily hummed. They continue to represent a reservoir of readily accessible music to the vast listening public of this region. Yet, many have criticised the role of song in cinema; on the grounds that it takes centre stage while all else -- plot, character, situation and denouement -- is pushed into the wings.

Those following the western tradition have done away with the song almost entirely; perhaps keeping one or two as background score or else singing voiceover. Such big names as Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Khawaja Ahmed Abbas fought against the romanticism fostered by grandiose notions of melodic design which they believed was anathema to their idea of gritty realism. In the midst of the raging debate, Khayyam chose to neither abandon the song nor to downplay its significance; instead weaving it into the very fabric of both plot and character. This was successfully reflected in the film Shankar Hussain. Though audiences were not won over and lamented the demise of the song as a stand-alone offering. Thus box-office success was still dependent upon the catchiness and memorableness of this film score genre which had become a welcome blueprint for local cinema-goers. From the 1970s onwards, Khayyam gave audiences what they wanted with the films: Aakhri Khat, Umrao Jaan, Kabhi Kabhi, Razia Sultana and Noorie.

For many, Khayyam was a composer of the old school that placed melody subservient to the tonal structure of the raag. This afforded certain leeway when it came to manipulating the number of surs (notes) to reflect the emotions being played out on screen. Nevertheless, original melodic resonance remained the primary focus. Khayyam was not overly fond of modern instruments or those of the West; favouring the organic sound of local instruments.

He was not alone in his fascination with the inherent possibilities of a single melodic structure. For example, finding himself totally besotted with raag pahadi, Khayyam included this genre in a large number of his compositions. He managed every time to make the score sound wholly original. Heer Ranjha was his first film. Going on to work on non-mainstream projects, he succeeded in producing film scores that are still recalled today. That he became a sought-after composer in the 1970s was due not only to the quality of compositions -- but also to their popularity among ordinary folk.

After co-writing the film score for Heer Ranjha (1948) with Rahman Varma, Khayyam composed the song Akele Mein Woh Ghabrate To Honge for the film Biwi (1950); sung by Mohammed Rafi. Then came Footpath (1953) and Shaam-e-Gham Ki Kasam, to which Talat Mehmood lent his voice. Both of these became huge hits. Khayyam received even greater plaudits for his work on the film Phir Subah Hogi (1958), which included the songs: wo subha kabhi to aayegi; aasman pe hai khuda aur zameen pe hum; and cheen o arab hamara. This is not to forget Shagoon (1964), which boasted parvato ke pairo par shaam ka basera hai.

Khayyam won three Filmfare Awards: for Kabhi Kabhi (1977), for Umrao Jaan (1982) and a Lifetime Award in 2010. He was also awarded the National Film Award, the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award for creative music and the Padma Bhushan by the Government of India in 2011.