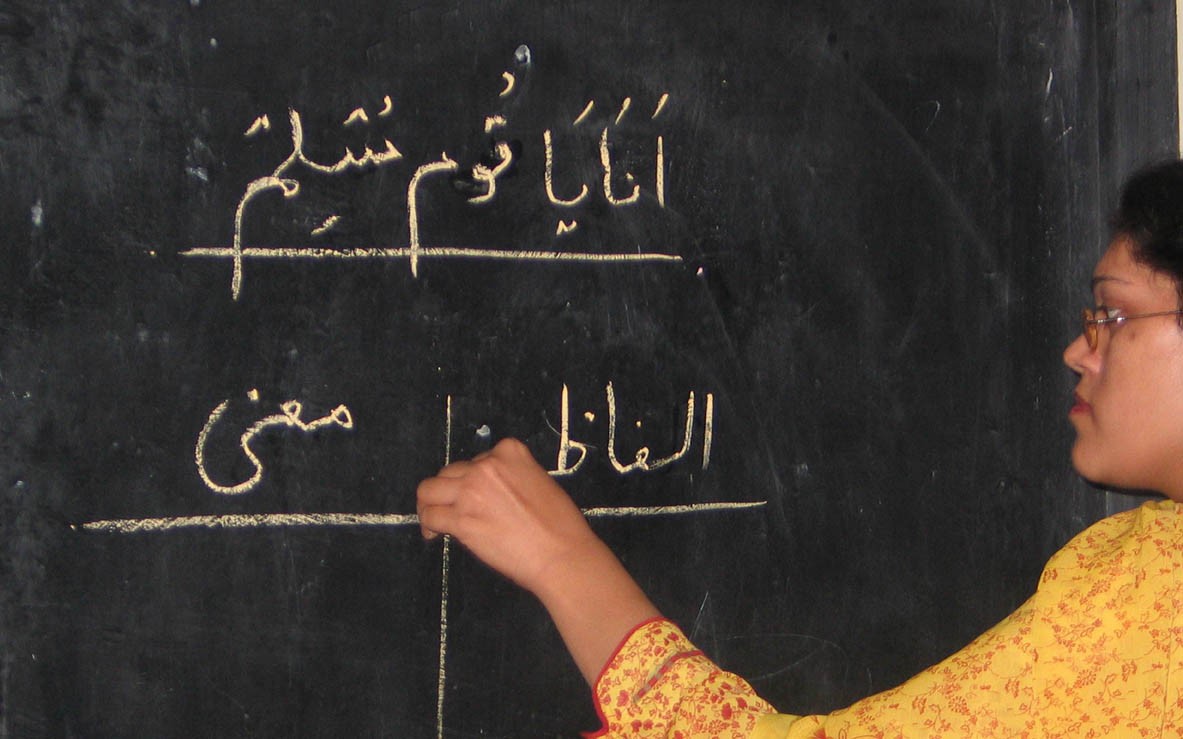

Analysing the Punjab government’s decision to revert to Urdu as medium of instruction at the primary level in public schools

Schooling in a foreign language

I had several Chinese cohort mates in grad school. One of them is now director of a research centre in the US. It took her a couple of semesters before she began participating in classroom discussions, which carry considerable weight in American grading system. At one point she confided in me about the trouble she was having with English, which she had learnt as a foreign language, but not used as a medium of instruction. She described the process in her head as (1) translating an English sentence she heard into her mother tongue, (2) making sense of it, (3) thinking of a solution / response in her mother tongue, (4) formulating it as a sentence, and then (5) translating that sentence back into English. However, by the time she had gone through these steps, the conversation in class had already moved on. That was grad school, and she had the benefit of 16+ years of schooling to cope with her situation.

Imagine the struggles of a child, who only knows her mother tongue and may have limited exposure to Urdu, in an English-medium primary school classroom. If foisting English on students was supposed to make our students fluent in it, we have not only failed in that objective, but messed up the teaching and learning of all other subjects as well. Under these circumstances, going to a school that teaches in English must feel a bit like going to a foreign country every morning. This, despite the fact that most "English medium" school instruction still occurs in Urdu or local languages, with English terminology plugged in, because most teachers lack the fluency to conduct an entire class in English. All "English medium" means is that the textbooks and exams are in English.

There is consensus among education and early childhood development researchers on the importance of teaching in the mother tongue, and the fact that disadvantaged children (poor or whose parents are not educated) perform poorly when taught in a second or third language. We need citizens who have not just just rote-learned English, can speak more than memorised phrases and read while also comprehending. In fact, in our context, for many children Urdu is still only their second language. It would be even better to teach them in their mother tongue. These children will be in a much stronger position to grasp a new language later if they learn the basic structure of their own language first.

A recent article titled The perils of learning in English in The Economist concluded that "Teaching children in English is fine if that is what they speak at home and their parents are fluent in it. But that is not the case in most public and low-cost private schools. Children are taught in a language they don’t understand by teachers whose English is poor. The children learn neither English nor anything else."

Punjab’s new language policy

As part of its education reform package, the language of instruction in the Punjab’s public schools is to be changed from English to Urdu. However, private schools teaching in English and preparing students for international school certifications like IGCSE, O/A-levels, will not be affected by these reforms. Changing the language of instruction is only one element of the education reform effort initiated in the Punjab. The Standing Committee School Education Department chairperson Aisha Nawaz Chaudhary says that the government has formed a high-level committee, called the CAST (Curriculum, Assessment, and Staff Training), to steer and oversee the process of education reform in the province.

To summarise, the reform process began with the development of the provincial curriculum framework, along the lines of the national framework, but updated to include 21st century skills. Following the development of the New Curriculum framework, textbooks for up to Grade 6 have been developed in Urdu. Over the following months, a consultative process will be conducted to bring stakeholders on board. Once the textbooks have been revised and finalised, teachers will be trained to teach from them. The same process will be repeated for up to Grade 8 and up to Grade 12 in subsequent years, in a phased approach.

I am curbing my expectations from this round of reforms. The revision of curricula, textbooks, exams and staff training are all things that fall within the purview of the CAST committee and have been done and re-done before, using similar processes, but with no significant improvements to show. To see if this reform process shakes out, we will first have to see at least the new curricula and textbooks it produces.

Life for millions of Pakistani children

For those who still insist that the government is taking schools backward by teaching children in Urdu, here is a reality check based on a recent extensive survey that was conducted by a project I worked on.

The per-capita-GDP of Pakistan in 2017 stood at $1,548, which comes to Rs13,545 per month. Households earning less than Rs7,000 per month likely occupy dwellings in a mud house without access to gas year-round, no television, no smartphone, do not own any means of transportation, are likely illiterate, do not have books at home and do not read to their children.

Households making between Rs7,000 and Rs27,000 per month may still occupy mud houses or a simple brick structure, may have access to gas, have an even chance of having a TV, about a third will have access to a smartphone, not own a car, and only half will have access to a motorbike. A quarter of them will have access to some kind of computer.

Households making between Rs27,000 and 55,000 per month likely inhabit a brick house, will have a TV, but still lack access to a computer, smartphone, but may have a motorbike. However, they are still unlikely to read to their children or do any activity with them that helps them academically.

These children are unlikely to grow up watching Sesame Street, or Dora the Explorer, or Barney, or Curious George, or Arthur like your children and mine have. There is likely no one in their immediate environment who speaks English, perhaps not even Urdu. These children struggle at school even without being subject to the added pressure of learning in a third language.

Limitations

Although a step in the right direction, changing the language of instruction is not a panacea, but only one piece of the learning puzzle. The new language policy will not make up for under-qualified, under-resourced and unmotivated teachers. We still need to hire, retain and support better teachers. We still need to develop a curriculum that is useful and relevant and prepares children for the next phase in their educational career, be it vocational training or college, and life.

There is also the question about whether public schools will lose students, whose parents insist on an English-medium education, to private schools. We know that even poor parents send their children to private schools, if they can. The most frequently cited reasons are better governance and instruction in English and computer studies. Parents from most socio-economic classes believe (perhaps rightly) that their children have a better chance to compete for a decent life if they achieve fluency in English. This is also an argument often employed by well-meaning but clueless Pakistani elites who criticise government’s decision of changing medium of instruction to Urdu. What they do not understand is that they are disconnected from and do not represent the class that goes to public school I described above.

The language policy will be a net positive, as long as children learn. However, the policy will not be neutral in its effects. In the worst case scenario, children will not learn English and their learning outcomes will be dismal like they are right now. Disparity between those learning in private and public schools will remain, or may widen even further. The cultural gap will remain and perhaps also widen because children with stronger socio-economic backgrounds will be more globally connected, as language will not be an issue for them. Children from public schools will remain at a disadvantage unless there is a dramatic improvement in the way English is taught and learned as a second language.

A word of caution

The idea of changing the medium of instruction for the vast majority of students to Urdu is certainly well supported by research and well-intentioned. However, we should tread carefully and not let the pendulum swing too much to the opposite extreme. A small but significant portion of our population speaks or at least understands English, which gives our workforce a significant advantage over many other countries in the international labor market. While the scientific consensus says that schooling should be conducted in a child’s mother tongue, let us not give up entirely our competitive edge in the English language inherited from our British colonial past. This may not be the right choice for the majority, but English is most definitely the language of international business, commerce, science, technology, medicine and research and will remain so for the foreseeable future.