Education, skill development, health, and conveying norms of mutual coexistence are some of the major areas that need attention

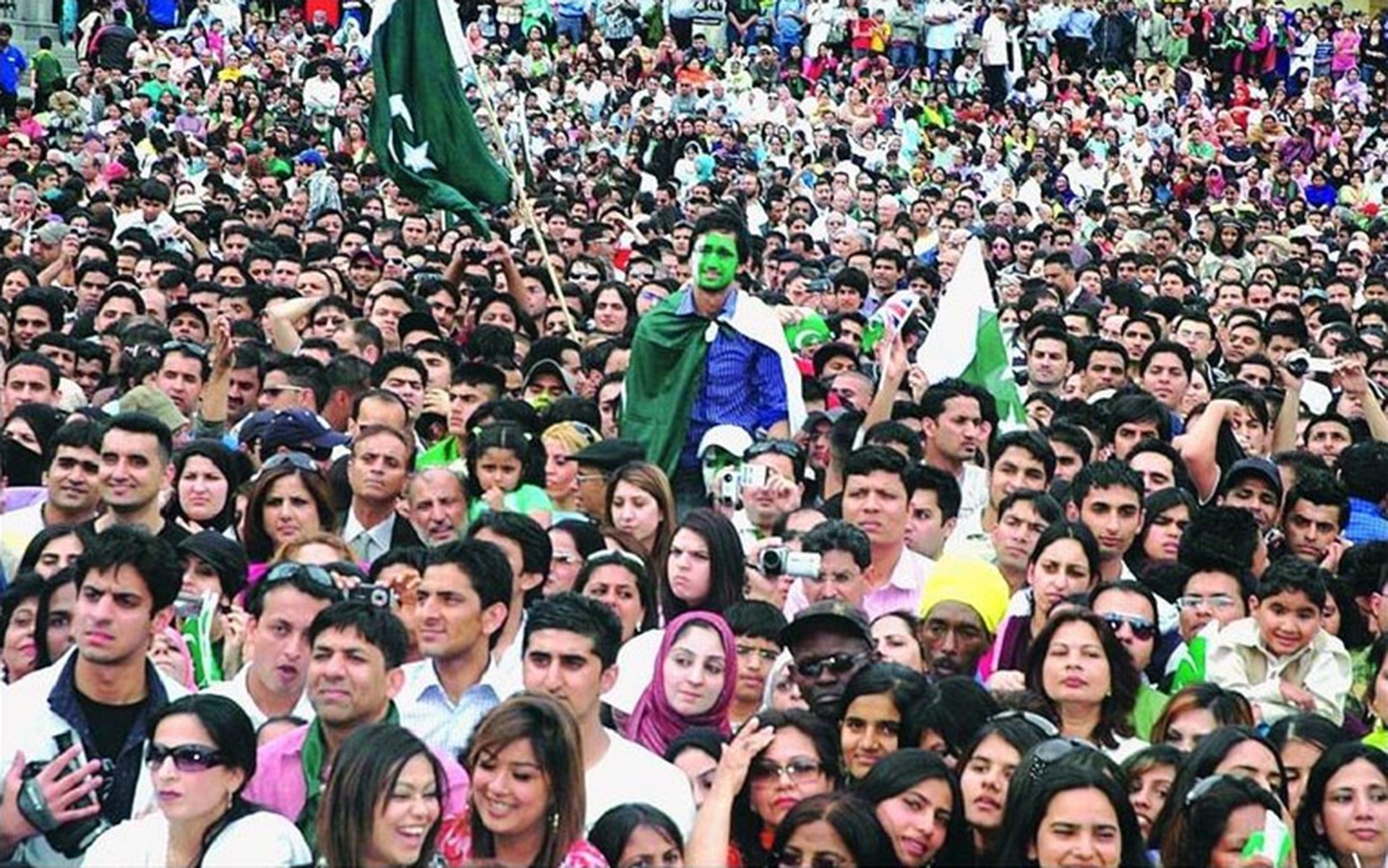

Pakistan has more than sixty million people 15 to 29 years old, which is approximately a third of its population. The youth have their peculiar needs and demands. This has repercussions for every field of life: social, economic, cultural, political and religious. They are not just demanding: they are impatient about their demands as well. Harnessed properly, the energy of the youth transforms a nation.

The heightened interest in youth in recent years is rooted partly in the changing demographics of the country. The much-delayed decline in fertility levels has resulted in a youth bulge.

Not only are the numbers of 15-29 cohort the highest ever their proportion in the country’s total population is also the highest ever. The very concept of the demographic dividend has emerged from the demographic transition. But the ‘dividend’ is not automatic. It must be earned.

There is no comprehensive policy for the youth. A young person’s life has many facets, all of them inter-related. Any attempt to compartmentalise them would risk making our insight flawed. Evidence suggests a poor state of human capital. Pakistan is ranked 125th out of 130 countries in the Global Human Capital Development Report in a study conducted by the World Economic Forum, with the young doing not much better than the old.

Young people with Ph.D degrees, protesting in the streets to demand employment are a warning to policy makers. On the one hand, we have too many out-of-school children for comfort and, on the other, we have a large number of unemployed graduates.

It can be argued that education having no nexus with the labour market’s current or future needs is to blame. The youth have not been imparted the right skills. Their overall capacity to be usefully employed is thus limited. And yet, education is not a priority of the state. This is reflected in the median years of education being a low 4.6. It is time to go back to the drawing board with a focus on quality and relevance of education, not just quantity.

Projects suggest that given the current population and employment trends, Pakistan needs to create 4.5 million jobs over the next five years. With an improved labour force participation the number will increase to 1.3 million jobs per annum (6.5 million in five years) to employ the new entrants in the labour market. That cannot be achieved without a holistic policy, linking education with employment. Opting for vocational training, instead of general education, can be one way of going about it. Poor literacy and bleak job prospects are a recipe for disaster. The presence of unemployed young people is emerging as a major factor in violence in many developing countries.

Evidence suggests a similar trend in Pakistan where a study found three per cent of the young people admitting to some kind of violence. Escape from poverty, defending their own or family’s honour, being unemployed or being bored featured prominently among the reasons for violence. So did religious and political motivations.

People aged 15 to 29 years are not a homogenous group. Any policy designed for them needs to provide for intra-group differences. To start with, the younger young (15 to 19), the middle young (20 to 24) and the older young (25 to 29) have different needs. Then there are major differences across the sexes and among the young belonging to the varied economic, social, religious and regional backgrounds.

An efficient youth policy, one that helps both the individual and the country, should look at the labour force characteristics and the state of human capital, disaggregated by sex, and the rural-urban differentials. Education levels and participation in the labour market, though getting better, show visible gaps for females. In addition to low labour force participation, a a large number of females employed as unpaid labour shows the skewed nature of the labour market in the country.

One factor that has a bearing on all these issues is marriage. Many decisions regarding education, employment and mobility are linked to prospective marriage. The median age to get married for females in Pakistan remains under 21 years, resulting in early child-bearing. By the time they are 29 years old, 68 percent of the Pakistani females have experienced motherhood. With low use of contraceptives in the country, even lower in this age group (with modern contraceptive used by 17 percent), it is the start of a long period of child-bearing, which in many cases starts from the teenage. This makes involving females in active economic roles a daydream.

Also read: The implementation part

The youth also have a low rate of civic participation and volunteerism, which says a lot about both the society and the youth. A time-use survey showed that a major chunk of the day is spent even doing nothing and/or sleeping/relaxing/lying down. These rates are higher for urban youth than rural ones and for young females than young males. The high rates for doing nothing coupled by low rates for civic participation show a lack of involvement in society.

Major areas that need attention to make the youth productive include education (that is of acceptable quality and relevance), skill development (instead of focussing on general degrees), employment (that is gainful), civic participation (that gives a feeling of belonging to the youth), health, and learning of norms linked to tolerance and mutual coexistence to avoid possibilities of conflict and violence. This is not an easy agenda to cater for but one that is absolutely urgent if we want to make the best use of our youth bulge.

The writer is Director Research, Pakistan Institute of Development Economics (PIDE), Islamabad