An artist is a political being constantly aware of his surrounds. But can he or should he avoid exposing his thought and personality through his paintings?

In a country where political discussion is a favourite pastime, the option to remain non-political is also a political position. Families, friends and colleagues are divided along party lines. Politics becomes a faith-system, the leader a messiah whom they follow ad nauseam.

Politics has affected every area of life including the world of creative expressions, especially the fields that employ words like literature, theatre and film etc. Politics also impacts visual arts. Historically, painting, sculpture and other representational forms were used to convey messages to the masses: about divine kingdom, ruler’s power or to invoke revolutionary sentiments. It was presumed that folks unable to access the written language could understand narrative told through images better. Till the recent past, art served as a tool to motivate people towards a higher cause, hence the term ‘political art’.

It’s tricky to define ‘political art’ or for that matter even ‘politics’ in art. Works that were made for a specific political agenda are now appreciated for some other content. Or works not created to describe or comment on the political situation are now read as the testimony of those conditions. For example, novels and short stories of Intizar Hussain, which did not have an apparent political theme, are the best example of the socio-political conditions of his times. Though he would have denied the label of a political writer because labels narrow the horizon of a creative person and his output. Spanish writer Javier Marias elaborates on this: "Nothing irritates a real writer more than those critics, professors and cultural commentators who insist on labelling him or setting him in context…"

However artists as sensitive people do reflect on the currents of their times. They may be least interested in politics, but if they are investigating reality they are bound to be political. They may stay away from political matters all their lives, still one discovers social and political content in their work, much relevant and daring than those who actively pursue a cause.

Yet, creative people have often been actively involved in political struggles. In the past, artists and writers have fought wars, have participated in uprisings and have been a part of revolutionary movements. Their works reflect mark of ideologies. Take novels by Andre Malraux, paintings by Jacques-Louis David and poetry by Leopold Senghor and Faiz Ahmed Faiz. There are other creative personalities that enjoyed freedom in their lives and art, despite oppressive governments, and produced highly charged works. Among them are Pablo Neruda, Bertolt Brecht and Pablo Picasso (particularly his paintings on Korean War and ‘Guernica’).

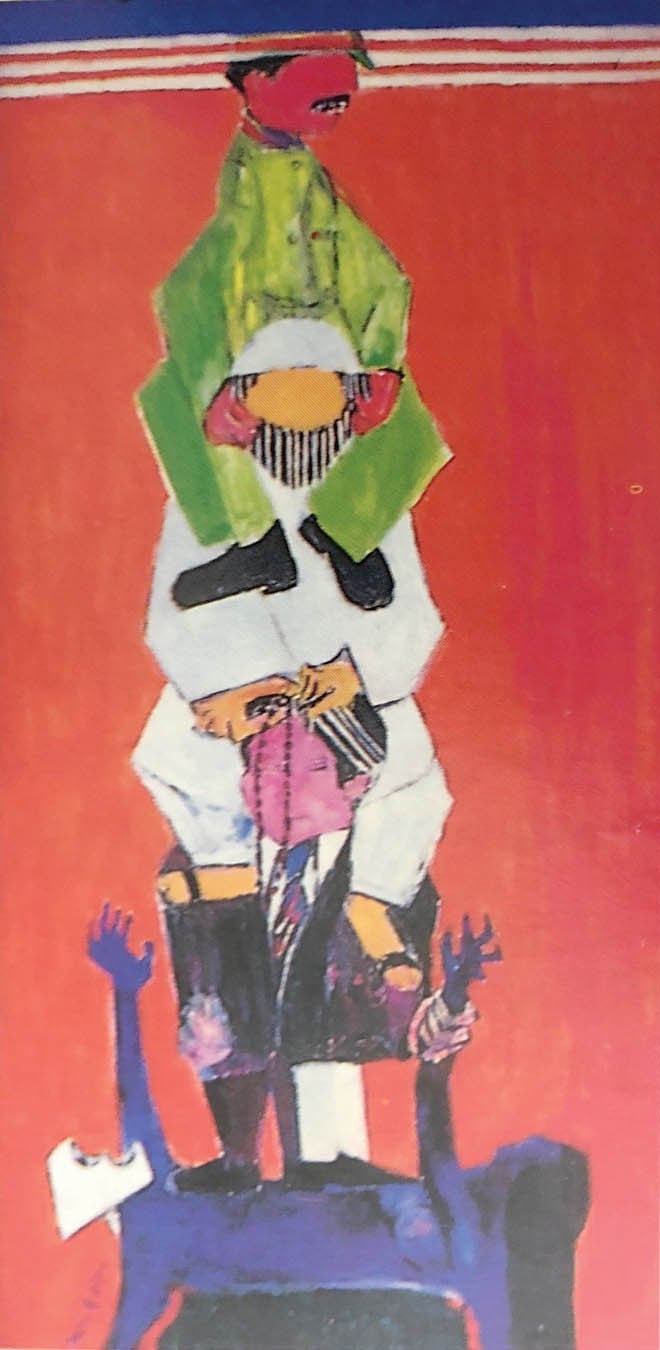

In Pakistan, too, political content can be found in artworks by artists that belong to a political group or support a cause. Artist Ijaz ul Hassan, who has worked with trade unions and contested elections as a PPP candidate, engages with local and international political situations in his art. His detention in the Lahore fort during Ziaul Haq’s times led him to formulate a pictorial language endowed with metaphors of windows and overpowering/surviving plants.

A number of other Pakistani artists have struggled against the suppression of women, ethnic groups and class through their art. Salima Hashmi drew nude female figures in the era of Zia. Another work addressed the massacre at Palestinian refugee camps of Sabra and Shatila by Israeli military in 1982. Likewise, A.R. Nagori challenged religious and military bigotry in his paintings. A legacy that is visible in the works of Jamal Shah and Akram Dost Baloch, though a bit muted. Some contemporary artists engage with politics as the subject matter but due to the blurred ideologies of our times prefer indirect idioms.

On the other hand, some artists like Ali Imam and Lala Rukh were thoroughly involved with the political and social movements in Pakistan, but their work does not reflect that side of their personalities. Imam was a member of the Communist Party of Pakistan and he got arrested in 1949 for three months in the Rawalpindi jail for a speech against the government. But his subsequent career as an artist remained disconnected from his revolutionary past. Similarly, Lala Rukh fought for the women rights and minority and ethnic groups, yet her artworks executed in different mediums do not remind of that position. Then, Sardar Aseff Ahmed Ali, the former foreign minister and a member of parliament, focuses on landscapes, still lifes in his work but certainly not politics.

Perhaps these artists realised the difference between the meaning and the message. Lala Rukh’s work is still relevant because it is not about ephemeral situation of a society. It unfolds the interiority of a person, exposed to the outside world of seashore, sparse outline of a human figure, lights of a city at night. Perhaps, once these artists know how to deal with the ‘inner’ world, they are able to tackle the other more troublesome worlds as well.

Another example in this regard is of Rasheed Araeen. While living a life of a migrant in Britain, he fought against inequality towards coloured artists through his art, activism and writing. Recently he has been represented at different international art exhibitions, such as Documenta, Venice Biennale, Sharjah Biennale, Jameel Prize, Art Dubai etc., but at most of these venues one comes across his formal constructions executed in the language of abstraction, devoid of any apparent political content.

Yet who knows a future critic may view this body of work as entirely political, created at a time when the vocabulary of modernism was reserved for mainstream western art, and an artist coming from the periphery had burst into the codifies of Abstract Art, though taking another path -- reinforcing the structure of Muslim geometry in his sculptures and paintings.

Colin David and Jamil Naqsh painted nude female figures regularly and were not bothered with the political in their art. Their focus was purely on formal issues of space, texture and painterly mark, all attained through female figure. But an artist is not a hermit, even if he seldom leaves his studio (like Jamil Naqsh); he is aware of the community he lives in, pressures from the state and problems of the public. Still if he continues to pursue his preferred subject, a female nude, for instance, which is not easily acceptable image for general public (Colin David’s solo exhibition at his house/studio in 1990 was ransacked by a mob), there is a figment of resistance. One knows that there was no hostile reaction to Naqsh’s nude figure, yet it was not kosher for the local art market - including official collectors such as the state guesthouses, foreign offices, embassies, and residences of rich puritans.

Regardless, both David and Naqsh kept on creating what they liked most. In a society that determines and decides on what to depict or not, this is remarkable (who knows a future critic may view artworks by these artists as political!).

Such artists decide to adhere to their own voice instead of following or obeying the doctrine of power (and public). Their choice to paint what they prefer is a significant form of political act. Without baptising it such.