Writing on art is whole new world, an independent discipline that does not require a practising hand but a command over language

Years ago, I was sitting in the office of the incomparable artist Salahuddin Mian, then Head of the Department of Design at the National College of Arts. He and another faculty member were arguing about a work from the recent faculty show. Having failed to convince his colleague, Prof. Mian asked, "How long have you been teaching?"

"21 years", came the reply.

"In these 21 years, did you read a single book on art?" asked Mian.

"Why do I need to read? I teach studio course!" was the prompt answer.

That was the end of the discussion.

That teacher was not alone in thinking like this; many artists then believed that indulging in reading would constrain their creative power, and had a contemptuous attitude towards the written word in general.

Today, the situation is not as bleak or hostile. One spots books on art (not catalogues or coffee table volumes) in the hands of art students and on the shelves of artists’ studios. However, visual artists still hold a certain bias regarding who is qualified to write on art. They often reject those who have never had first-hand training in studio art, because to them only art education provides the licence and right to comment on art-making. They don’t recognise the importance of having a discerning eye. Or that writing on art is an independent discipline that does not require a practising hand but a command on its medium: language.

Traditionally, writers on art can be divided into four groups: philosophers, art critics, artists and literary authors. Thinkers from Nietzsche, Kant, Schopenhauer to Foucault, Derrida, Barthes, Baudrillard, Deleuze and Arthur C. Danto have written on art in different capacities. Then we have a long list of art critics, with Akbar Naqvi and Marjorie Husain being two eminent names in our midst. A number of artists have also written on art, including Barnett Newman, Robert Motherwell, Elaine de Kooning, Jean Dubuffet, Antonio Tapies, Alan Kaprow, Barbra Kruger, David Salle, Victor Burgin, and K.G. Subramanyan to name a few. A common element in all the groups is their specialised field: philosophy, art history/theory, or art practice.

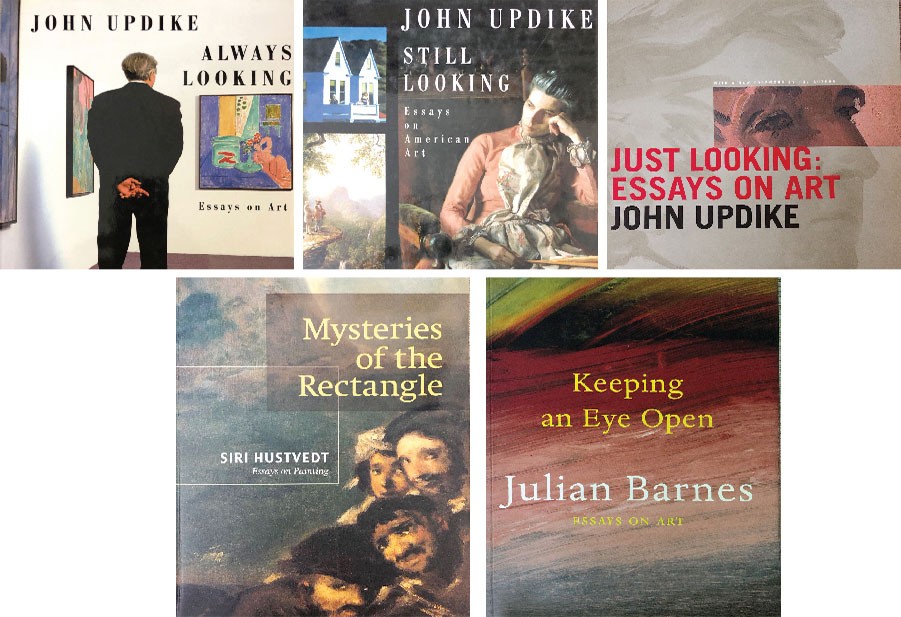

But when it comes to writers who are primarily known for literature, their texts on art have a different flavour altogether. Apart from an in-depth analysis of artworks, they are the masters of craft of writing. Hence one gets information as well as pleasure while reading an essay/article on an artist or an artwork; let’s say after Baudelaire, we had Jean Genet (Fragments of the Artwork), John Updike (Just Looking, Still Looking, and Always Looking), Karl Ove Knausgaard (So Much Longing in so Little Space), Julian Barnes (Keeping an Eye Open), Siri Hustvedt (Mysteries of the Rectangle), A.S. Byatt (Portraits in Fiction) and Argentine author Cesar Aira (On Contemporary Art) along with many others.

Probably the finest example, though not the first, in this regard is a collection of essays on art by Julian Barnes, the Booker Prize winning British novelist. An inventive of form, as in his novel A History of the World in 10 ½ Chapters, one finds art writing blended with reflective essay to complement/complete the narrative. Keeping an Eye Open starts with a chapter on Gericault’s painting ‘The Rafter of the Medusa’ (the one included in his novel). But the more you read the more you are awed by the author’s insight into the intricacies of visual arts as well as forming connections with other strands of society and painters of the past. His essay particularly on Ron Mueck is illuminating since he brings references from medical history; and other artists who explored similar aspects of human body and practices that do not necessarily fall into art.

Likewise for Mysteries of the Rectangle by Siri Hustvedt: an American novelist writing on painters such as Giorgione, Vermeer, Chardin, Goya, Morandi, Joan Mitchell and Gerhard Richter in such a way that one forgets that fiction is her main domain. Her perceptive reading of imagery, linking biography of the painter to his picture and locating new links between images and meanings are far more illuminating and entertaining than a professional art critic or historian.

Actually, when you move from your main discipline to something else, albeit related, you tend to excel in it because here you are free to express and assert what you believe, without being conscious, careful or clogged by the pressure of your profession. Being practitioners of literature, it liberates Barnes and Hustvedt to comment and contemplate on a piece of creativity outside the realm of letters. That position provides a sense of freedom to approach art in an unconventional or un-academic scheme. Thus their views and how these views are weaved into words invite a reader to go back to the text, again and again. Much like the strategy of a painter who entices, provokes and forces a viewer to keep on looking at his painting for a long period.

The charm of words adds to the attraction of images. However, one is a bit confused if one is enjoying the artwork more or the writing on it? It resurrects the memory of a music piece in which at one point the voice of female vocalist and the sound of flute merge in such a scheme that one can’t differentiate between the voice and sound.

At the end of the day, it is the world of words regardless of whether we enter through the door of fiction or under the arch of art. Or approach it from the path of philosophy or the track of history. These are words. And writers who are magicians have the power to use them, thus their texts on art are enjoyed both for their opinions as well as for the beauty of writing. So even if an artist goes out of fashion or is not liked by a certain reader, yet the master writer makes him/her as attractive as the character of a novel to often trap a reader.

One reads French essayists, English novelists, American authors writing on art and artists, even Moroccan novelist Tahar Ben Jelloun on Alberto Giacometti, and yearns for Urdu writers penning similar texts on artists. There are a few or almost none -- an occasional piece by Muzzafar Ali Syed, some sentences of Faiz, personal anecdotes jotted down by Intizar Husain, and that’s it. Quratulain Hyder, who could have been the most relevant person to write on art in Urdu, just mentioned art in passing while talking about the structure of novel in Urdu in one of her essays. A few articles on artists such as Jamil Naqsh, Masood Kohari and a few others by Nasim Neshofouz (published in literary magazine Seep) are exceptions.

Perhaps the reason for western authors to write on artists is based on a culture in which a child goes to a museum and sees works of art, studies art history at an elementary level, is later exposed to it while watching TV, reading Sunday papers or listening to interviews on radio. For a man of letters, the world of pictures is not an alien or strange domain; it is familiar ground. This is contrary to what is happening around us where the realm of art is an exclusive island which can be imagined by a number of Urdu writers but cannot be reached.