The stress on trying out something new can result in the loss of centre that is supposed to put everything in some order

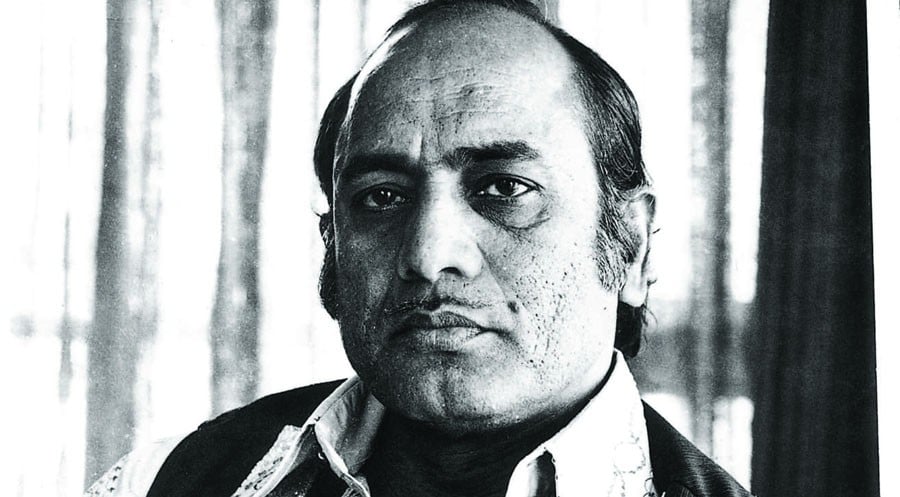

The death anniversary of a leading ustad is also a time for reckoning and reviewing the state of the form that the ustad excelled in.

Needless to say, Mehdi Hassan excelled in singing the ghazal and he probably took it to the point from where it seemed very difficult to go any further and higher, the only path that it could take was downward.

Some lovers of music may not agree with such a categorical assessment as in the ghazal after Mehdi Hassan as they may also see virtues in terms of its development keeping in view the current pattern of music-making.

But the intonation has changed so much in the last two to three decades that it seems very difficult to imagine a person or an artiste singing in the same pattern that is the ghazal, with guitar in hand. Coke Studio has been experimenting with the orchestral arrangements and instrumentation that is more computer-generated and, so to say, contemporary and it has also put some of the famous ghazal numbers through the mill stones.

It may be odd to take the name of an instrument in connection with the form of music but it seems that the sarangi can be mentioned in the same breath as the kheyal and the harmonium similarly with the rendition of the ghazal.

It may be noted that most of the leading composers in films were actually very good harmonium players and the instrument played, in more ways than one, the role to become the representative instrument for film composition. Most of the early music composers all either composed for theatre or were harmonium players in the orchestras that were meant to play music for the plays. It may be stressed that these orchestras did not only play background score only, thought these did, but that role was minor in comparison to the accompaniment to the vocalists.

All plays in the sub continent in the major tradition had a number of songs, some more than others, and music particularly singing became the benchmark for success in the theatre plays and music, acting being pushed down the order. Singing was considered to be an indispensable part of an actor’s performance and those who sang badly were dropped like hot potatoes.

The early ghazal maestros were either those who were trying their hand at the films, since with the talkies singing had become an indispensable part of performance, or were thumri exponents who found the audiences thinning out in comparison to the ghazal and, especially the ghazal that was being sung by those who had made a name for themselves in the films.

Two examples that come to mind readily are that of Akhtari Bai Faizabadi and Kundan Lal Saigal. Ghazal must have been sung in the salons of the dancing girls in the beginning of the twentieth century along with thumri and dadra but it only reached an elevated status with the two mentioned above, after they had made their mark in the films.

In India Anup Jalota, Pankhaj Udhas and, above all, Jagjit Singh took up the challenge and basked in the reflected glory of Mehdi Hassan and the leading Pakistani ghazal exponents. But the loss in interest in the ghazal as a form of literature may also be the reason for it to be sung less and less and it started to take on the song format or that of the geet. The decline of the standard of Urdu may have been instrumental in the vocalists too losing faith in the form.

But the change in intonation has made the rendition of ghazal more problematic in the contemporary world. Either there has to be a totally different definition of how the ghazal is sung or the way the other traditional forms are sung or it could be and for that one will have to wait for a great vocalist or a musician to arrive. These days it is a little difficult to point to one in the making.

In Pakistan, there have been three great exponents of the ghazal gaiki -- Farida Khanum, Iqbal Bano and Mehdi Hassan contributing in many similar and dissimilar styles to the evolution of ghazal gaiki in the last fifty years or so. Before them, however one can trace a whole development which led to the fructification of this gaiki in Pakistan.

After Gohar Jan, Mukhtar Begum and Akhteri Bai Faizabadi made great contribution in the development of the ghazal gaiki. Three other exponents of the ghazal gaiki, Ustad Barkat Ali Khan, Rafiq Ghaznavi and Muhammed Hussain Nagina had already enriched it. Actually, it was Ustad Barkat Ali Khan who brought the thumri ang of singing into the ghazal gaiki and, hence, started a new trend that was to characterise this form for the next many years to come.

Some other names should also be mentioned in this regard. Shamshad Bai was a good ghazal singer as was Bhai Chhela. And who can forget that Payare Sahib, too, was held in high esteem once. Ijaz Hussain Hazravi, too, enriched the gaiki of the ghazal and made it more acceptable to the diehard fans of music more hinged on the classical forms. Ghulam Ali, too, has popularised ghazal gaiki both in India and Pakistan.

The ghazal took its formal inspiration from the kheyal gaiki and as the kheyal gaiki ranged supreme ghazal too survived in its shadow but with its decline, especially in Pakistan it took over and appropriated many of the virtuosities and graces of that classical gaiki. Film music too prospered because of the endemic classical tradition and with its being pushed into the shadows film music, too, is seeking inspiration from other sources.

Now due to the media and technological revolution music of the entire world is the raw material for creation and the great freedom of choice is probably a spoiler. The stress on experimentation and trying out something new can result in the loss of centre that is supposed to put everything in some order.