Understanding Pakistan’s social and historical milieu

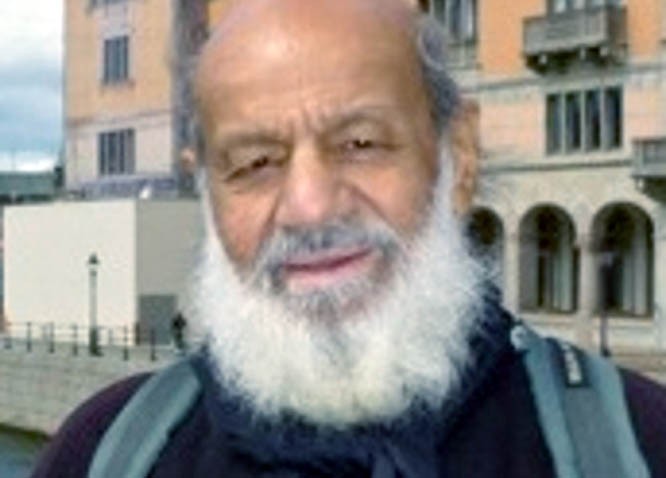

Sudhir Chandra is an eminent historian who primarily specializes in 19th century India. He has been engaged largely in understanding ‘the nature of modern Indian social consciousness as it began to shape as a consequence of colonial intervention’. His books Oppressive Present, Gandhi, An Impossible Possibility and Dependence and Disillusionment are testimony to the intellectual depth and wide-ranging erudition that are on display when Chandra lends expression to his thoughts. In several meetings with him and his wife Geetanjali when they visited Lahore in 2005, we had had several sessions of debate encompassing various themes pertaining to history and social consciousness.

It was really a treat talking to such a seasoned scholar, whose intellect was coupled with modesty. When I asked him how he understood the social reality that had been shaped by the historical process particularly in the postcolonial world, his answer was precise but at the time I was not able to fully understand the implications. He characterized that social reality as one defined by ‘ambivalence’. For someone trained in the positivist tradition of doing history as I was, such a one-word response was a cause for flustering. It also demonstrated my scant acquaintance with postmodern theory and the impact it had on the discourse of history. Having always been taught that verifiable fact is the prime constituent of the historical discourse as well as the social situation described through it, I opted to keep quiet though somewhat grudgingly.

However, after several years of that interaction I eventually started making sense of Sudhir’s response when I began to analyze various episodes of Pakistan’s history. The change in the collective perception of the people regarding the reign of General Ziaul Haq is a typical case in point. After 31 years of his demise the scale of history shows a visible tilt against his grand image as Mard-i-Momin-Mard-i-Haq. His projection through the prism of history is more as a villain than a hero. The inherited problems of terrorism, drugs, religious militancy, the undermining of democratic institutions and the enhanced role of the Army in civilian affairs are all attributed to Ziaul Haq. Even those who were once encomiasts of Ziaul Haq, like Mujib-ur-Rahman Shami and Altaf Hassan Qureshi, have stopped calling him Shaheed (martyr). They think it advisable in the current circumstances to keep mum about their erstwhile darling leader.

Quite conversely, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, despite his mercurial nature and at times vindictive behaviour towards his friends and foes, has been deemed as an emblem of democratic values and the champion of the dispossessed. Even Nawaz Sharif and his acolytes have stopped castigating Bhutto as a symbol of indiscretion and impropriety. Ironically, both Sharif brothers despite being the political progeny of General Zia emulate Bhutto’s style of leadership, oratory, his attire and even his gimmickry. The supporters and the leadership of the right-wing political parties, who never tired of implicating Bhutto as the main culprit in the secession of East Pakistan have now accorded him a discreet nod of credence as the only true political leader since Mr. Jinnah.

In the intellectual and literary realms, Faiz Ahmad Faiz, Saadat Hassan Manto and Habib Jalib have forced their way into the mainstream at least to the extent that they are recited and quoted by people across the ideological divide. Shahbaz Sharif draws immense pleasure in reciting Jalib in public rallies. Whether there is any commonality between the views that Jalib professed all his life, and the political ideals that the PML-N has practiced and epitomized, is a question for which far more space is required than what this column warrants. The point here is that these intellectual figures did not enjoy this kind of acceptability and amenability in the 1980s and 1990s. Back then, they were projected as representatives of subversion and immorality, therefore they were not discussed even in institutions like Punjab University. Mercifully things have changed now. These figures have been national icons for the past 15 years or so.

Now we return to ‘ambivalence’ and examine how it reflects in Pakistan’s socio-political history. First, let us explicate the term ‘ambivalence’. Ambivalence is a state of having simultaneous conflicting reactions, beliefs, or feelings towards some object. One can put it differently by saying that ambivalence is the experience of having an attitude towards someone or something that contains both positive and negative valences. The term also refers to situations where "mixed feelings" of a more general sort are experienced, or where a person experiences uncertainty or indecisiveness.

In the postcolonial situation, various socio-cultural sensibilities tend to create a state of ambivalence. Thoughts and practices embedded in the traditional social order become convoluted when they intersect with multiple manifestations of modernity; hence ambivalence is the outcome.

In the social and historical milieu of Pakistan, ambivalence manifests itself in the visible divergence between thoughts and practices. Simply put for the sake of clarity, reciting Faiz’s revolutionary and progressive poetry while practicing the regressive ideas and thoughts professed in the times of General Zia, is the ambivalence that we are caught in.

Thus, our engagement with progressive ideas is limited to paying merely lip service but in practical terms, we are stuck with stagnated concepts of state and society. Therefore, our status as citizens and subjects is the subject of ambivalence, as articulated by Homi Bhabha. Generally, ambivalence reflects ideational potency and makes multi-culturalism and social plurality a possibility. It stems the one- dimensional ideology to nurture which ought to be hailed as a big blessing. But in any state of ambivalence in any social formation, multiple ideologies which exist simultaneously move horizontally to create a new social synthesis.

Sadly, in Pakistan, ideology is one-dimensional; therefore, the only direction in which it can move is vertical. Consequently, the peculiar nature of ambivalence that we find in our society perpetuates socio-cultural and ideological stagnation. Ideas and practices, or thought and ritual, do not lend support to each other, which obviously presents worrying prospects for our future. Social alienation and chaotic action results when there is no connection in what you believe and what you practice.