Taking a look at Mujh Se Pehli Si Muhabbat from a previously unexplored perspective

Literature, unlike other forms of discourse, is profuse in its multiplicity of meanings, that is, it offers a contested site of polysemy -- meanings or layers of meanings; diverse, divergent and, at times, competing against one another. However, a propensity for preferred readings dictated by our personal idiosyncrasies, socio-political orientations and ideological formations regards the literary text as a mere fossilised object of enquiry. As a result not only do we keep sticking to our routine and clichéd interpretations but also become susceptible to overlooking pauses, silent moments and blank spaces that offer significant messages encoded deliberately or unconsciously within literary texts.

This is by no means to suggest that one should shun a realist understanding and appreciation of literature, but a critic must be alive and alert to truth-claims and be able to delve deep into textual structures.

Let us take a few examples from our literature. First, a famous couplet by Iqbal:

Uthaa Kar Phaink Do Baahar, Gali Mein

Nayi Tahzeeb Ke Ande Hain Gande.

These two lines that come at the beginning of a short poem may be roughly translated in the following way:

Pick and throw them out in the alley

The eggs of the new civilisation are rotten.

A new civilisation, as we all know, stands here for Western civilisation and the point needs no elaboration that Iqbal, as he was championing the cause of the Muslim Ummah, regarded Westerncivilization as a perpetual Other of his own. Though the poet, at times, confesses and, at the same time, laments the realisation: ‘my intellect is Western/European’ (Meri Daanish Hay Afrangi), but he is also undisputedly one of the harshest critics of Western civilization, and in that capacity he warns his coreligionists apocalyptically against its supposed onslaughts.

The above-mentioned couplet may not be a proper example of his artistically refined poetry, but, thematically it does represent a strand of thought that accompanied our poet throughout his literary life and in this way it can be taken as truly representative of his ideological regimes. Now, the critique of Western civilisation is clear,and this is how this couplet is interpreted and quoted and rightly so. But let us visualise the site of enunciation and try to locate where the poet is to be found in this couplet. He mentions only one location: an alley. But he is not there as the word ‘outside’ in the first line indicates. He is somewhere inside -- possibly in a house -- from where he urges his fellow inhabitants to perform the act of tossing the rotten eggs. Now, we see two locations: the house - the private space, and the alley -- the public space. We can take these two spaces also as distinct signifiers of individual and society. Now we see that the poet-protagonist urges us to pick the eggs, as they are already rotten, from the private space and throw them out in the public space. Surely this is not the message that the poet consciously wishes to convey to us. He wants to warn us sincerely against Western intellectual onslaught, but the latent message of differentiation between a private and public space -- a clear-cut prioritisation of the first and downgrading of the second -- surfaces as a powerful sub-text, so powerful that it can render the so-called main text as a superficial façade.

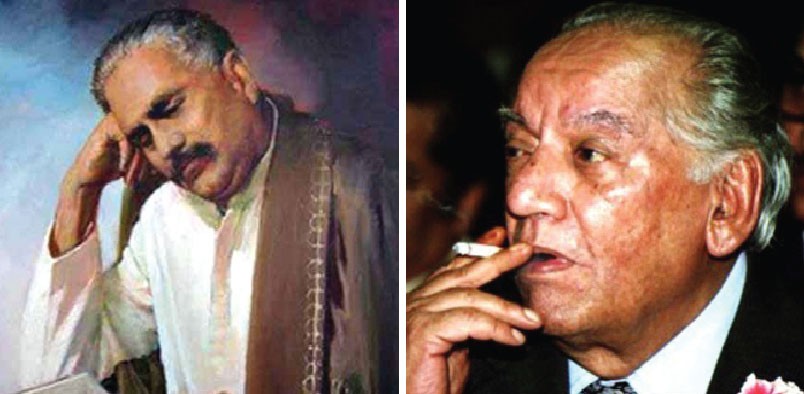

For the second example we can take a famous poem by Faiz, arguably one of his representative pieces of poetry:

Mujh Se Pahle Si Mohabbat Mere Mere Mahboob Na Maang.

Written at the juncture of love and revolution -- a trope typical of the Progressive Movement, this poem hashaunting images of the female body, nostalgia and the transience of life. Above all, it is considered the epitome of Faiz’s intermingling of Gham e Jaanan and Gham e Dauraan, that is, of romantic love and social concerns. The male protagonist - the only speaking subject -has been in love till now. He tells his female counterpart that though she still retains her feminine charm, he now has to break the bond between then and leave her in order to pursue a nobler and loftier cause to help the downtrodden and wretched of the earth. The female, a deposed beloved, is silent, or ‘rendered’ silent by this abrupt and frenzied change of mind from her co-traveller, his immediate and unanticipated disengagement from a mutual affair and a reciprocal process. But here, she hears a unilateral decision; neither is she asked to give her opinion nor requested a camaraderie on the new ideological journey -- she is just handed a final decision. Majaz, one of the brilliant poets in the progressive camps, has an almost similar issue in his poems:

Nau-Jawaan Khatoon Se (To a Young Lady).

Tere Mathe Pay Ye Aanchal Bahut Hi Khoob Hay, Lekin

Too Is Aanchal Se Ik Parcham Banaa Leti Tau Accha Thaa

[Quite suits this veil to your forehead thoughBetter you had made a flag with this piece of cloth.]

Here, again we are confronted with the dialectics of femininity and revolution -- again a male subject is addressing a female figure. However, now we find a mild, polite and gentle suggestion that gives latitude to the other party of accepting or rejecting the proposal. There is something mature, dignified and human about this utterance. The protagonist in Faiz’s poem, on the other hand, imposes a decision -- a decision that verges on a dictation. Here class consciousness is in focus but at the cost of sheer oblivion of gender sensitivity. Here abstract humanism is much more important than a human being made of flesh and blood.

The above examples were selected from poetry only for lack of space. Any literary form or genre can be put to this scrutiny. One can, for instance, have a look at Manto and examine his perspectives on women, the female body, and especially the question of female agency in his narrative scheme. This is important also for the reason that Manto -- a keen observer and a harsh critic of social life and human conditions -- had always abhorred hagiographies. It would probably have come as a surprise to Manto to see the way he is being converted into a cult -- a sanctified personage -- with an eternally defined message.

A reader -- especially a critic who is none other than a keener, a more alive reader and is surely not in any way a credulous fool -- is supposed to take each claim made by a writer with a grain of salt. Seeing things barely on their face value gives not only a superficial appreciation of the given text, but it has, in most cases, a devastatingly dangerous domino effect that keeps on corrupting generations to come with a facile and fallacious mindset.

It is high time that we braved the hackneyed and hegemonic epistemologies traditionally transmitted and taught and mindlessly followed in our literary culture, especially in the academy, and cast a fresh, profound look at our literature: a literature that presumably has the potential to erode our erroneous notions and help inculcate a weltanschauung - more sublime.