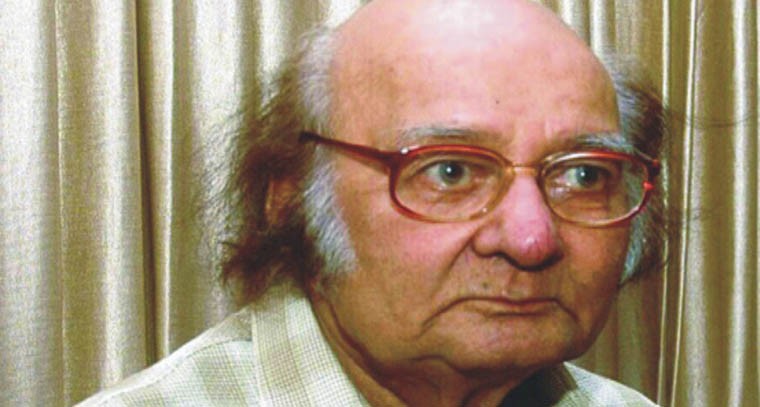

Dr Jameel Jalibi was an original thinker and one of the leading lights of Urdu literary criticism

Perhaps every person can dream of such gargantuan things that only gods can achieve, yet there are few who ultimately succeed in materialising these dreams. Dr Jameel Jalibi was one of those fortunate yet hard working people, who believed in the power of resolution, consistency and disinterestedness.

In his early thirties, he started thinking about composing a detailed history of Urdu Literature -- a gigantic task that required institutional setup, resources and support. He knew well how challenging it was to collect old manuscripts and rare books preserved in public libraries/personal collections across the subcontinent and in libraries of European countries. He knew it was an unwieldy and costly business and deciphering, organising and interpreting these resources into a history of literature was another huge, intellectual commission, but he was clearly up to the task. Moreover, he had a strong predilection for criticism, editing, translation and lexicography. He held top positions in superior services of Pakistan and at Karachi University, Urdu Dictionary Board and National Language Authority (now National Language Promotion Department).

To be pragmatic and imaginative at the same time is a rare simultaneous occurrence. In his case, it happened. Dr Jameel Jalibi, who was born in Aligarh on July 30, 1929, breathed his last in Karachi on April 18, 2019. Hardly a month ago, Pakistan’s most prestigious literary award Kamaal-e-Fun was announced by Pakistan Academy of Letters in recognition of his lifetime achievements.

As for his critical works, Tanqeed Aor Tajruba (Criticism and Experiment), Nai Tanqeed (New Criticism), Muasir Adab (Contemporary Literature), Adab, Culture Aur Masail (Literature, Culture and Issues) and Muhammad Taqi Meer, are some that deserve a particular mention. The idea of culture interwoven with the notion of tradition seems to have engrossed his critical approach all along. In postcolonial Pakistan, the first question that drew the attention of Urdu literati was: "what is Pakistani Adab (literature)?" This question was epistemologically coupled with the question of Pakistani Culture. It was being presumed that culture is an identity marker of any society and all imaginative and intellectual artefacts and traditions are manifestations of culture. But the question of culture and tradition proved thorny. To form a clear idea of culture and tradition Urdu writers either resorted to western thinkers and critics or to medieval Muslim thinkers and theologians.

Dr Jalibi by and large went with western critics, particularly with 19th-century English critic Mathew Arnold (1822-1888) and 20th century Anglo-American T.S. Eliot (1888-1965). From Arnold, Dr Jalibi took the idea of precedence of criticism over creativity and its cultural role. T.S. Eliot’s theory of tradition can also be traced to Dr Jalibi’s notion of organic unity that he tried to find across the six centuries of Urdu literature.

Arnold proposes that it is criticism that harbingers a new era of creativity; criticism precedes creativity. He holds that dissemination of a new set of critical ideas -- gathered from diverse disciplines -- spurs the imagination of creative writers. In the same way, Dr Jalibi was of the view that the discipline of criticism cannot be confined to just evaluation of literary texts, rather it should create new, inspirational cultural ecology that could ignite the imagination of poets and fiction writers. Dr Jalibi also firmly believed in the cultural role of criticism. Though the idea of cultural (and historical) criticism was challenged by the American New critics in the 1940s who held that it is the form, not content that not only draws a line between literary and non-literary texts but forms the aesthetic value of literary texts. Dr Jalibi continued practising cultural criticism. He looked askance at critical theories that emerged in the second half of 20th-century, for example, Structuralism, Deconstruction and Postmodernism, that revolutionised the ways and methods of interpreting literary texts and made us see how they actually took part in the construction of reality instead of just reflecting it. The ideas of criticism, culture and tradition, that he assimilated in the early years of his literary career, can be found throughout in all his works.

He edited classical and modern literary texts; on the one hand he edited earlier Urdu texts produced in Deccan, for instance, Nizami Ganjvi’s Masnavi Kadam Rao Padam Rao, Deevan-e-Nusrati and Deevan-e-Hasan Shauqi along with Qadeem Urdu Lughat -- all a by-product of his History; and on the other Kulyat of Meeraji, the 20th century modernist Urdu poet. He also edited books on the life and works of Meeraji and NM Rashid. He edited Urdu literary magazines too; Saqi for a brief period and Nia Daur for a longer period. Translation was his vocation; for the purpose he chose essays of western criticism and Aziz Ahmad’s books on Islamic Culture and Islamic modernism. In selecting western critical essays, he seemed to trace the tradition of western critical thinking that runs uninterruptedly from Aristotle to T.S. Eliot. These essays were published under the name of Arastoo Say Eliot Tak -- one of the best books on western criticism available in Urdu.

By exhibiting an interest in classical Persian and Urdu literature on the one hand and modern Urdu and western literature on the other, and giving equal importance to both criticism and research, he seems to have followed the tradition set by Muslim scholars of the colonial era. Quest and striving for Muslim selfhood were the order of the day in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The displacement and marginalisation the Muslims of India had to experience under colonialism forced them to explore and interpret their past -- well-maintained in and through classical Arabic, Persian and Urdu texts -- in a bid to find some tenable ‘place’ and a plausible ‘centre’, prerequisite for identity and selfhood.

In his criticism in general and on the history of Urdu literature in particular, he seems to be absorbed in the pursuit of organic unity -- an imaginative order that could not only bind up the past and present in a single whole but also couple distinct cultural acts into a harmonious accord. To achieve organic unity, he ventures to gather earlier instances of Urdu literature in the ‘places’ and ‘centres’ of Muslim rule i.e., Punjab, Sindh, Delhi and Deccan. He firmly believed that in pre-colonial India after Persian it was Urdu that became a site for construction of Muslim selfhood. Following Hafiz Mahmood Sheerani -- who authored Punjab Mein Urdu (Urdu in Punjab) in 1928 -- he held the view that Urdu was ‘born’ in Punjab -- so it became the first ‘place’ and ‘centre’ of construction of Muslim identity -- in the wake of the Ghaznavid rule in the 10th century, which travelled to Delhi and Deccan with Muslim rulers. Sheerani’s theory was challenged by Masood Hasan Khan twenty years later in his book Muqqadama-e-Tareekh-e-Zuban-e-Urdu (An Introduction to the History of Urdu Language) which proposes that Urdu has grown out of Khari and Haryanvi bolis (dialects) which were spoken in and around the adjacent areas of Delhi.

But Dr Jalibi stuck fast to the theory that roots of the Urdu language are deeply embedded in the geographical areas that form present Pakistan. The four volumes of his history of Urdu Literature are an attempt at reinforcing the said theory of birth and evolution of the Urdu language. His history of Urdu Literature is ‘modern’ in the true sense of the word. Firstly, it is not just an accumulation of historical facts about authors, events and texts, rather it critically evaluates and interprets texts in their socio-politico-cultural perspective and organises them into an organic whole. Modern theories of historiography don’t see any ‘fact or text’ that came into existence at a specific period in isolation, rather they couple fact and texts with interpretation; and no interpretation can be done without employing some sort of perspective -- political, cultural, philosophical or nationalist. This explains how multiple histories of Urdu literature came into being. Secondly, Dr Jalibi’s History echoes a nationalist ethos.

The fourth volume of History begins with a long chapter on Mirza Ghalib and ends with a detailed essay on Ismaeel Meerthi (1844-1917), one of the earlier poets who initiated the school of modern, natural poetry in Urdu under the influence of Lahore based Anjuman-e-Punjab and the Aligarh Movement. We can assume that Dr Jalibi would have been working on the fifth volume that intended to cover 20th century Urdu literature. One wishes that Majlis-e-Tarqi-e-Adab, Lahore, publisher of Dr Jalibi’s History, completes the project by commissioning a team of scholars.

The writer is a Lahore-based critic, short story writer and author of Urdu Adab ki Tashkeel-i-Jadid (criticism) and Rakh Say Likhi Gai Kitab (short stories)