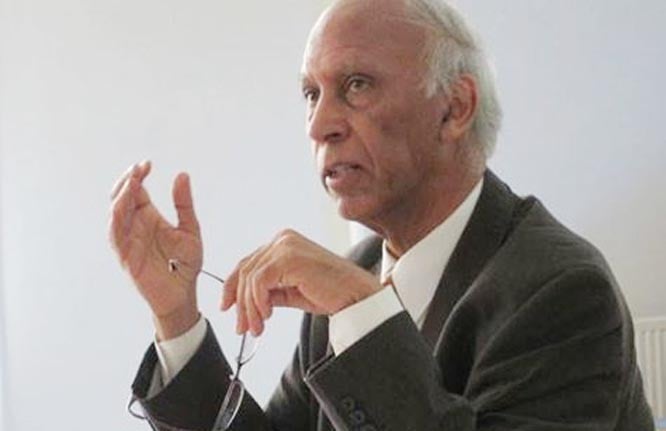

At the 5th Jamil Omar Memorial Lecture, organised by the Awami Workers Party in Lahore recently, Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed addressed key questions on the subject of Partition

Under the wine-coloured sky, leaving behind their dearest homes and deepest histories, 7.2 million people fled carnage and migrated across the Indian subcontinent.

In the dead of the night of mid-August 1947, perpetual Hindu-Muslim conflict finally sliced a land that had for always shared modes, manners, rites, and customs. Much more than just life was lost. And for what? Religion? Had not the people of the land consolidated into empires under Prithvi Raj and Mahmud of Ghazni and Aurangzeb? Had not the communal antagonism been accepted as a side-product of the tremendous diversity where the minorities took turns to face atrocity, depending on the reign of the Mauryans, Guptas, or Mughals? The 5th Jamil Omar Memorial Lecture, organised by the Awami Workers Party in Lahore recently, addressed such questions on the subject of Partition.

The lecture is organised every year to commemorate the death anniversary of Professor Jamil Omar, a veteran leftist who led his life struggling for democracy. This year, the Swedish political scientist and author of Pakistani descent had been invited to give a lecture, titled ‘Partition and the formation of a Garrison State.’

"India had always been a subcontinent of nationalities," stated Prof Dr Ishtiaq Ahmed, the keynote speaker for the lecture, in which he enumerated the events and circumstances that led to independence.

Why then the two-nation theory? Are not there two nations in South Africa, the English and the Dutch? What about Switzerland? Are not the German, French, and Italians living in harmony? Obviously, India was not the only place plagued by communal antagonism. If it had not troubled the French in Canada and English in South Africa, why then should it be impossible for the Hindus and Muslims to accept a single constitution? And if Pakistan was hailed as the holy shield that would protect all Muslims, who would safeguard the Muslim minority in the Hindu dominant provinces? Was not Pakistan unnecessary for Muslims where they were already in majority, and had no fear of the Hindu Raj?

Dr Ahmed enumerated the events and circumstances that had led to independence. A recount of the riots, marches, and protests might propel one to think that Pakistan was a consequence of a futile cause, that the creation of Pakistan and the politics of All India Muslim League slaughtered common tradition, common race, common languages, and a common country all in its arrogance to claim responsibility for a group that, for centuries, had survived and flourished without independence. Why, then, the need for partition?

Having a ‘choice’ became the ultimate cause of the inevitable partition of subcontinent, and the British can be credited with no more than having expedited the process.

India was a hugely diverse land and was only unified into a single state when under imperial rule by one group or the other. European imperialism was not distinguishable in its exploitation and tyranny only in its import of the nation-state ideology, which permeated the West during the 18th and 19th century.

Dr Ahmed remarked, "Nation and nationalism are the salient phenomena of the era of capitalism and industrial society. Just as religion was the supra-ideology of the medieval and early modern period, nationalism has been the supra-ideology of the modern period beginning with the 18th century."

The British brought with them modernisation, industrialisation, centralisation and, most importantly, liberal constitutionalism, and in doing so planted the idea of having a choice, completely foreign to the Indian people.

In recounting the timeline from the introduction of direct elections and formation of Legislative Assemblies, by the Government of India Act 1919, to the complete independence to draft constitution, in the Cabinet Mission Plan 1946, Dr Ahmed built a narrative of how a system of political organisation was bequeathed to the Indian people, which drove them to divide their land. The British, inadvertently, set up a meritocratic bureaucracy, an independent judiciary, a legislature, an executive, an independent press, and a civil society, and invested in these institutions to perpetuate their empire. Many Asian intellectuals, having gained training and education from the West, fell victim to the ideology of European liberalism and, in an attempt to reconcile it with the circumstances of India developed and advocated for a strong sense of nationalism. In the words of Dr. Ahmed, "These… models of nationalism held an attraction for colonised people of Asia and Africa. These were led by indigenous elites usually educated in colonial educational institutions and many had studied metropolitan universities and legal schools."

Mohammad Ali Jinnah and Muhammad Iqbal were among the proponents of nationalism. By 1916, Lucknow Pact declared Muslims’ right to separate electorates and, by 1930, the Allahabad Address promoted the two-nation theory and the idea of an independent nation.

Dr Ahmed later moved to an explanation of the role of the two-nation theory in the formation of Pakistan. Here is where the role of Jinnah becomes important. Although Jinnah for long was convinced of and worked towards a unified nation, he finally acquiesced to communal conflict that was in part a product of Muslim nationalism and the resulting political demands.

Muslim League’s persistent insistence on separate electorates, although advertised as protection for the Muslim minority from Hindu political dominance, did more to exacerbate the communal conflict than bridge it. The demand for adequate Muslim representation centred on the apprehension that in the absence of constitutionalised safeguards, the minorities would be subject to atrocities at the hands of Hindus. But Jinnah’s demand for independent representation welded in the steel-frame of a single government was counterintuitive. It was a shortsighted method of self-protection. No community in Canada, South Africa, or Switzerland ever thinks of a separate communal party for it is self-evident that if the minority separates itself into a unit demanding separate rights so will the majority, and pitting a minority communal party against a majority communal party will easily lead to majority communal raj. Therefore, in demanding weighted representation the Muslims hoisted themselves on their own petard.

But it could not have been otherwise. The Muslim identity was too deeply entrenched, and the import of the nationalist ideology only added fuel to the fire. In the end, it was not the Muslim grievances, the refusal of Congress to recognise the Muslim League as a representative party, the refusal of Congress to form coalition ministers but the theory of nationality embedded in the theory of the sovereignty of the will of a people.