Looking back at events fifty years ago that led to ouster of General Ayub Khan

This March 2019 marks the 50th anniversary of getting rid of the first military dictator in Pakistan, General Ayub Khan, who was forced to resign on March 25, 1969. He ruled for almost 11 years with an iron hand. But in this essay we are not concerned with his early years. Here we will discuss the second half of his regime from 1964 to 1969. In the first part of this essay we will discuss the period from 1964 to 1966, and in the second and last part we will highlight the major parties, players and points of contention that led to his downfall from 1967 to 1969.

The first five years of his rule from 1958 to 1963 were a period of demolition of democracy. All political activities and parties were banned and the press was strictly controlled. He had imposed highly centralised constitution for which he had formed a commission led by a former judge, Justice Shahabuddin. But ultimately the constitution of 1962 was the handiwork of Manzur Qadir, General Ayub’s law minister and one of the civilian pillars of the dictatorship. The constitution had concentrated all executive and legislative powers ultimately in the hands of the dictator.

After the promulgation of the new constitution, political activities and parties were allowed and a semblance of normalcy was coming back to the country. When 1964 started it was about time for the second elections of the local bodies that General Ayub had set up under the name of Basic Democracy (BD). In July 1964, five opposition parties, namely Council Muslim League, Jamaat-i-Islami, Awami League, National Awami Party (NAP), and Nizam-i-Islam Party met at the residence of Khawja Nazimuddin in Dacca (now Dhaka), and decided to form an alliance named Combined Opposition Parties (COP).

It is pertinent to mention that after suppressing all political parties for almost five years, General Ayub Khan had finally realised that he himself needed a political party. He tried to take over the good old Muslim League with some of the senior leaders of the party such as Chaudhary Khaliq-uz-Zaman. In a convention, some party leaders joined General Ayub Khan and the official Muslim League was now referred to as the Convention Muslim League. Other leaders, such as Khawja Nazimuddin, refused to accept the general as their leader, and had their own faction called the Council Muslim League.

After the formation of the alliance i.e. Combined Opposition Parties, it was decided that all component parties of the alliance would field joint candidates for the next elections. They also agreed on a manifesto calling for a democratic constitution, parliamentary system, provincial autonomy, slashing of presidential powers, and freedom of judiciary. Responding to this challenge, General Ayub Khan nominated himself as the official Convention Muslim League candidate for the next presidential elections to be held in 1965. Initially, Khawja Nazimuddin -- the second governor-general and prime minister of Pakistan -- was considered as the opposition candidate, but he was in deteriorating health.

Unfortunately, four great democratic leaders of Pakistan died in quick succession within two years from 1962 to 1964. They were Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy, Maulvi Fazlul Haq, Maulvi Tameezuddin Khan, and lastly Khawja Nazimuddin. General Ayub Khan hated all of them, as they were popular among the people of both East and West Pakistan and commanded great respect from the masses. All of them were Bengalis and represented 55 per cent population of Pakistan. With their deaths, General Ayub Khan was not expecting much from any other political leader. But there was a surprise in store for him.

In September 1964, Fatima Jinnah, a sister of the father of the nation M A Jinnah, accepted the Opposition’s request for the nomination as their presidential candidate. In January 1965, when the first presidential election was held, General Ayub Khan used his entire state machinery to defeat Fatima Jinnah. It was an indirect election in which 80,000 Basic Democrats voted to elect the president. Though, in the earlier BD elections that were held on a non-party basis, most candidates had won from the opposition. The general and his coteries had managed to coax or force the BD members to vote for the incumbent.

Even with all the rigging and repression, General Ayub Khan could only claim a narrow victory. Out of 80,000 electoral votes, he won just 49,000. In East Pakistan, the rigging was more difficult so he could claim hardly 20,000 votes from there. This farce of an election was a huge disappointment for the people of Pakistan and especially for East Pakistanis who had hope for the restoration of democracy and an increase in their say in decision making that was highly centralised in the hands of General Ayub Khan.

The Combined Opposition Parties refused to accept the results announced by the Election Commission. To counter this, a victory parade sponsored by General Ayub Khan’s Muslim League was held in Karachi. It was led by his son Gohar Ayub, and resulted in violent deaths of 23 people. This infuriated the people in Karachi who became even more violent so much so that the army had to take control of the city from the local police. This presidential election broke all records of manipulation by state institution against political parties and set the tenor and tone for many such episodes for the decades to come.

Interestingly, in this system of indirect elections, National Assembly was not yet formed. The people were neither allowed to vote for the president nor for the assembly members. The people only voted for the Basic Democrats who first elected the president and then in March 1965, 150 members of the National Assembly. As expected the official Muslim League won 120 seats and the remaining 30 by the Opposition and independent candidates. On March 23, 1965, General Ayub Khan once again took oath to remain president for another five-year term. This was the man who had been accusing politicians of being power-hungry and manipulative.

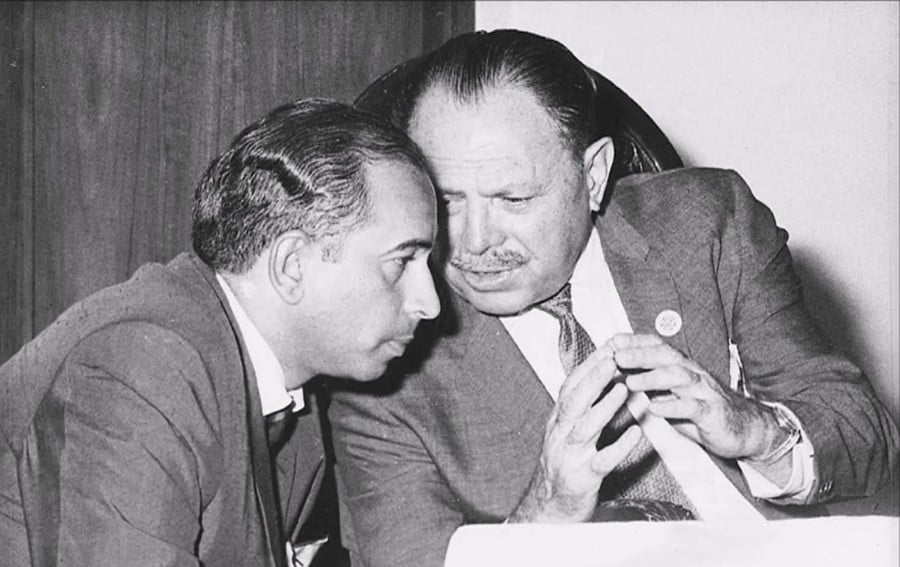

Shoaib and ZA Bhutto were Ayub’s close associates and were again sworn in as finance and foreign ministers respectively, and Bhutto was also appointed as secretary-general of the ruling Convention Muslim League, which we may call Ayub League. To thwart any opposition from the COP and to divert people’s attention from the mockery of democracy, India served as a handy excuse. In April 1965, Indian and Pakistani troops fought a major battle in the Rann of Kutch, a vast marsh and swampy land bordering Gujarat and Rajasthan in India and Sindh in Pakistan.

In addition to Bhutto, Shoaib, and many others, now another gem of constitutional gimmickry joined the general. Sharifudddin Pirzada was named attorney general of Pakistan in May, 1965. This gentleman would serve many dictators and undermine democracy in Pakistan whenever he could for the next half a century. After the presidential election held in January 1965, it took almost six months for the puppet National Assembly to come into existence. The oaths for the newly-elected members were administered in June 1965. With increasing tensions on the borders with India, the government reduced the development programme by five per cent to meet defence costs in the next fiscal year.

In July 1965, at least three important development took place. The US president, Lyndon B Johnson informed General Ayub Khan of a delay in aid commitment, apparently showing American displeasure at Pakistan’s improving ties with China and other communist countries. Earlier in the year, Foreign Minister Bhutto had been to the Soviet Union on a three-day official visit at the invitation of the Soviet foreign minister, Gromyko. The second development was on the part of Maulana Bhashani, NAP president, who assured General Ayub Khan that he would find all patriotic elements rallying round him to face any threat from outside.

Maulana Bhashani was an interesting personality. He claimed to be an Islamic socialist with a pro-China leaning. Though he led the National Awami Party, he off and on showed a soft corner for General Ayub Khan and his establishment. Bhashani’s announcement in support of General Ayub Khan paved the way for a rift within NAP that ultimately resulted in the breakup of the party in Bhashani NAP and Wali NAP.

The third development was related to air force in which Air Marshal Noor Khan was sworn in as commander-in-chief of Pakistan Air Force replacing Air Marshal Asghar Khan who retired in July 1965.

In August 1965, Prime Minister Lal Bahadur Shastri of India charged Pakistan with sending 3,000 to 4,000 infiltrators into Kashmir and warned of an attack if it were to continue. On September 6, India launched an attack on Pakistan along borders of West Pakistan, and General Ayub Khan declared an emergency in the country. Leaders of various political parties assured the president of their full support in war efforts. On September 22, a ceasefire is announced by both sides. After the war, two statements issued by foreign minister Bhutto deserve especial mention.

In October 1965, Bhutto announced that Pakistan had severed diplomatic relations with Malaysia as it had opposed Pakistan at the UN Security Council. In November 1965, on the last day of discussion on Indian aggression in National Assembly, Bhutto said, let the Indians manufacture an atomic bomb, but they cannot intimidate us. "If they have an atomic bomb, we too will have one even if we have to eat grass." After the war both countries claimed victory and projected heavy losses to the enemy. For details about the war, two of the best books are by Colonel Syed Ghaffar Mehdi and Brigadier Amjad Chaudhry.

Politics of Surrender and the Conspiracy of Silence first published in 2001 by Ghaffar Mehdi is a marvelous book of hardly 170 pages but it lays bare the inside story of the war. September 1965 by Amjad Chaudhry, published in 1978, accuses Yahya Khan of depriving Pakistan of a strategic victory by refusing to capture Akhnur. Ghaffar Mehdi quotes Mian Arshad Hussain who was Pakistan’s high commissioner in Delhi as saying that he sent a warning on September 4, 1965 to the foreign office of Pakistan through the Turkish embassy that the Indians were planning to attack Pakistan on September 6.

About the background of the 1965 war, we read on page two of Col Mehdi’s book that under Operation Gibraltar "Pakistani commandos were to be sent into Indian-occupied Kashmir to carry out attacks against Indian troops and installations. It was hoped that this would trigger an uprising by the masses. The Foreign Office also impressed upon the military top brass at the GHQ that the Indians would not risk a full-scale war by invading across the international boundary. General Musa, C-in-C of the Pakistan army and General Ayub Khan bought into this…without any critical evaluation or thinking."

Col Mehdi was commandant of Pakistan’s Special Service Group (SSG) and vehemently opposed the plan. He pointed out that in the absence of any ground preparations in Indian-occupied Kashmir, there was no chance of the plan succeeding. Instead, Col, Mehdi was relieved of his responsibilities as commandant of SSG and transferred to Sialkot.

In the next part of this essay, we will discuss the endgame of General Ayub Khan. (To be concluded)

Mnazir1964@yahoo.co.uk