Meher Afroz’s mixed media paintings at O Art Space are documents of our destiny, defeat, disappointment -- and delight

Faiz Ahmed Faiz in his poem ‘Zindan Ki Aik Subh’ (from the collection Dast-e-Saba) depicts the meeting of approaching morning and receding night -- in a long embrace as if of two lovers. The lines of poetry resurrect our memory of observing the way the two times are joined yet separated, in a zone called shafaq, which literally means "twilight, colours of the sky between sunset and nightfall, redness in the horizon at the sunset".

On occasions, this Urdu word also refers to dawn. Thus it can mean two times: when the light is either fading or emerging with the expanse of red on sky.

Meher Afroz, in drawing inspiration from another Urdu poet, Jaun Elia, has adapted the word Shafaq (from one of his verses about the adversaries of beauty who taint the atmosphere, dull the dawn, and extinguish the twilight), and made it the title of her solo exhibition at O Art Space, Lahore from March 7-16, 2019.

One can explore why Afroz selected the term shafaq at many levels, especially if we recall her background: her insight into socio-political matters; her grasp of cultural and literary concerns; and her formal choices in making an object of plastic art.

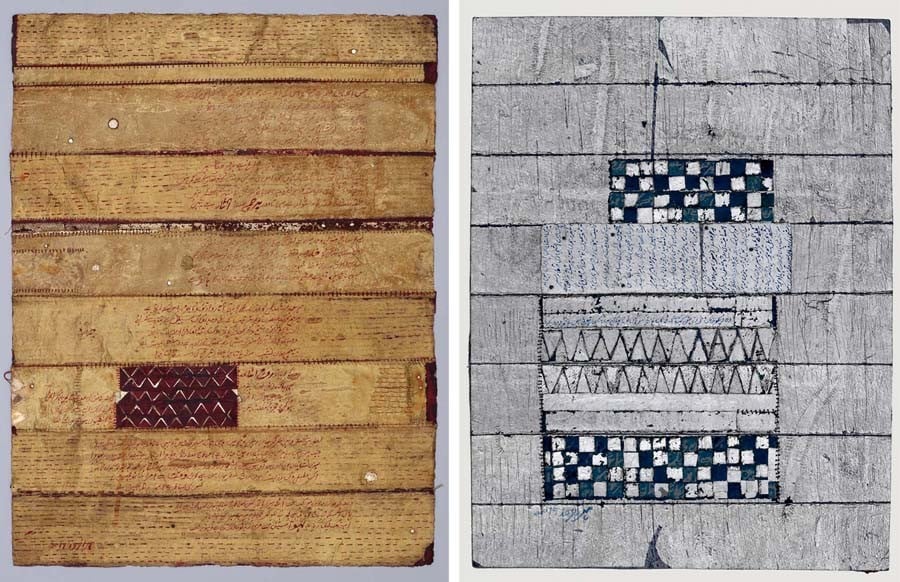

Regarding her formal choices, Afroz’s early training and experience of printmaking have played a pivotal part in determining and fixing her aesthetic route. Unlike artists who prefer bright colours, clear lines, sharp edges and crisp imagery, she opts for a language that is layered, physically and technically. Because when you are preparing an etching plate, printing a lithograph, working on a woodcut or making mono-prints, you are creating a surface that is rough, raw, stained and spontaneous. Accidental marks, occasional effects, arbitrary textures are important to determine the imagery and develop ideas. So a printmaker’s paintings often remind of a ruinous wall with cuts, faded colours, scratches and combination of various coats.

For a number of years, Afroz’s paintings have that weighted look and, in some instances, resemble old parchments, discarded panels or faded sheets. Traces of imagery, interplay of brushstrokes (which remarkably do not appear as brushstrokes) and a sensitive chromatic scheme mark her work. Afroz suggests a retinal solution that demands not an easy or immediate access.

This characteristic of her work can be linked to the notion of twilight, an area that is in-between (like the aesthetics of her pictorials which is not too obvious or direct). Several artists and writers have chosen this mode of expression -- to be able to say much more than what is intended. In Intizar Husain’s fiction, one stumbles upon the actual intent of the writer amid a story constructed with a lot of extraneous details.

In the same lieu, Meher Afroz alludes to a situation but does not announce it. This mode of expression, so much connected to our society and to our civilized manners, stems from our imperial and colonial past when one was not supposed to utter a direct statement till it was covered, merged and textured with ‘verbal acrobatics’ so as not to offend the Mughal emperor or English ruler. This practice continued into modern times; hence, in the age of military dictators, artists devised an idiom that imbibed the critique of the situation but refrained from immediate references. A formal selection, an artistic sophistication, or a political compromise, but in every case a blessing since it enabled a work to survive after its age and relevance.

As we leaf through the marsiyas of Mir Anees and Meerza Dabir, we read the account of an incident that happened 14 centuries ago, but what we pick is a commentary on the contemporary period. Likewise, on seeing the new work of Meher Afroz, we suspect that the geometrical shapes, texts scrawled at places, subtle distribution of silver, golden, grey and reddish hues are not merely objects, but are objectives to remind us of our own conditions. The main role and responsibility of an artist is to inform the audience about its reality, may be by making a mirror to reflect on people and places, or addressing the complexities that lie deeper than the picturesque settings of a community.

If one approaches the work of Meher Afroz through that prism -- notwithstanding the gallery curator’s explanation -- one recognises the subtlety in commenting on one’s surroundings. At places, one comes across texts, mainly words such as power and cruelty, or lines of poetry inscribed in normal order or sideways. Perhaps originating from Elia’s poetry, but who cares really! For the artist, the real intent is not to identify each and every word, but to get across a sense of some sort of shehr-e-aashob, the requiem of an epoch through pictorial tactics.

Her way of creating these highly political works is extremely personal. Layers of paints are applied to attain that vintage quality you find in a historical document. The grid, lines, script all remind of a page from the past, but the works seem more relevant when read in the context of the current situation. Afroz has stitched portions of her art pieces with thread which, for her, is a mark of healing, mending and joining, like in a medicinal procedure.

On another level, this feature brings her work into the domain of an art that was neither installed on gallery walls nor bought by collectors but was part of a devotional world, in which the life of Buddha and Bodhisattvas were painted on palm leaves that were joined with each other in the pattern of a booklet during the period of Palas (c. 800-1200 AD). It also connects to the document in possession of many households, the family tree or shajrae nasb, that traces the origin from a high ranking clan, and is extended at every stage through sewing another patch/page for adding new names. It also brings to mind the act of weaving and quilting torn pieces of fabric.

The fact that she has used simple lines -- basic shapes of square, rectangle and triangle -- is a testimony of a painter’s search for the primordial which can be classical, folk and popular at the same time. In another sense, these forms refer to Tantric manuscripts, Islamic geometry and Twentieth century (Abstract) art. Yet the binding element is the visual sensation; so when we look at these mixed media paintings, we tend to forget them as art, instead we approach these as documents of our destiny, defeat and disappointment -- and delight too.