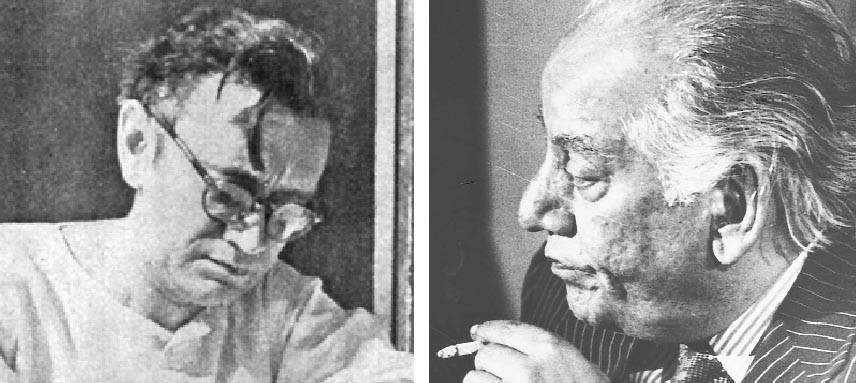

What lies behind the often misunderstood connection between Saadat Hasan Manto and Faiz Ahmed Faiz

January 18 was Manto’s 64th death anniversary and it should be noted that Manto has been experiencing something of a renaissance for quite a few years. Manto’s best short stories like ‘Toba Tek Singh’, ‘Mozail’, ‘Hattak’, ‘Naya Qanoon’, ‘Khol Do’ and countless others remain peerless both as works of art as well as searing commentaries on their times. However, even Manto’s most ardent admirers admit that his work is wildly uneven. Exquisite short stories are mixed in with works that are at best hurried and slapdash, at worst incomprehensible. Most of this is, no doubt, a result of the life that Manto lived: a life marred by poverty, alcoholism and mental illness.

In and of itself, this is of no moment. After all, an artiste is free to create and propagate his or her work anyway he likes. But the continuing attention on Manto has had the result of perhaps diverting attention away from a number of other gifted writers some of whom were his contemporaries and some who came later. Writers like Upendranath Ashk, Krishan Chander and even the great Munshi Premchand. In addition, later writers like the exquisitely subdued Ghulam Abbas and Muhammad Hasan Askari have not received the kind of attention or accolades that have accrued to Manto.

February 13 was Faiz’s 108th birthday and it seems appropriate to examine what connection (if any) existed between the two. In a couple of interviews, initially noted in Dr Ayub Mirza’s book Hum ke Thehray Ajnabi, Faiz said: "Manto was my student at the MAO College Amritsar (Faiz’ first job after finishing his MA)". Faiz went on to note affectionately: "He never studied much, he was mischievous. He…didn’t respect anyone. But he respected me and considered me his ‘ustaad’".

A recent column in a leading Urdu daily devotes a considerable amount of ink to disproving that Manto was ever Faiz’s student. It points out, correctly, that Faiz was appointed a lecturer in English at the MAO college Amritsar in 1935, probably in the latter half (the exact date is not available). Manto had, by then, already become a translator of some renown having translated and published some Russian short stories as well as Oscar Wilde’s play Vera among others. Manto did join the MAO college Amritsar as a student in 1933 but most likely had dropped out by the time Faiz joined as a lecturer. Subsequently, Manto was briefly a student at the Aligarh Muslim University but had to drop out after being diagnosed with tuberculosis. He returned to Amritsar in August 1935, probably right around the time that Faiz joined MAO college as a teacher. Manto then travelled back and forth between Amritsar and Delhi for treatment and in May 1936, on the advice of his physician moved to Bombay and later (after partition) to Lahore.

It seems obvious that Manto and Faiz were, in fact, present in Amritsar around the same time (mid-late 1935 till summer 1936). Faiz was an up and coming poet having received some acclaim for his poetry while still a student at Government College Lahore and then Oriental College from around 1929 till 1934/35. His poems had been published in Government College’s esteemed literary journal Ravi and his teachers, leading literary lights of the day including Sufi Ghulam Mustafa Tabassum, Dr MD Taseer and Ahmad Shah Bokhari ‘Patras’ were aware of his poetic talents.

In addition, in Amritsar, he was introduced to Syed Sajjad Zaheer and quickly became one of the leading organisers of the newly emergent All India Progressive Writer’s Association (AIPWA). All through this time, Faiz would undoubtedly have been reciting his poetry both at mushairas and perhaps private events even though the publication of his first volume of poetry Naqsh-e Faryadi was still some years away (1941). Many of Manto’s short stories were also published in the quarterly Adab-e Lateef which Faiz briefly edited around 1939-41. Faiz also defended Manto in court more than once. In Dr Ayub Mirza’s book, he said "Every time he (Manto) would be taken to court, I would be one of the defense witnesses. He was arrested four times; for ‘Kaali Shalwar’, ‘Thanda Gosht’, ‘Khol Do’ and ‘Dhuan’. The first three times we managed to get him off."

Manto was actually prosecuted six times for alleged pornography. In addition to the stories Faiz mentions above, he was also taken to court for his stories ‘Bu’ and ‘Ooper Neechay aur Darmiyan’. In 1949, Faiz was the convener of the Press Advisory Board tasked with rendering a judgment about whether Manto’s notorious short story ‘Thanda Gosht’, published in a special edition of the magazine Javed in March 1949 was a work of art or pornography. In short, the two were well acquainted.

When Faiz says in his interview "Manto apna shagird tha", he clearly means ‘Shagird’ not in the narrow sense of a student enrolled in a class one is teaching in a college or university but someone who seeks guidance from another who he considers more learned or erudite. In addition, when Faiz says "Woh meri izzat karta tha aur mujhay ustaad maanta tha", he clearly means ‘Ustaad’ in the Eastern/Indo-Pakistani sense, again, someone learned, older, more worldly who can be confidante/guide and mentor.

Manto, to my knowledge, never referred in writing to any association with Faiz and, fairly early on, dissociated himself from the AIPWA. From his meteoric rise as a short story and then film writer in the late 1930s and early 1940s, to his legal battles over being an alleged pornographer, through his fateful decision to migrate from Bombay to Lahore only to be dogged by continuing legal troubles, alcoholism, mental illness and penury into an early grave, he walked his own lonely path, refusing to compromise what he considered his artistic integrity, refusing to draw a cloak over the ‘unbearable society’ in which he lived.

In 1955, he died in Lahore at the young age of 43. Faiz, languishing in prison at the time under threat of a death sentence for the Rawalpindi ‘Conspiracy’ case wrote: "I was grieved to hear of Manto’s death. Respectable members of our community, who have neither the awareness of the fragility of an artiste’s heart nor any sympathy for it, will probably say that Manto himself is to blame for his death. But no one will wonder why he did this…The problem is that when life and art are in conflict with each other due to social circumstances, one of these has to be sacrificed. The other possibility is of mutual compromise, in which some part of both is sacrificed. The third possibility is to unite the two into a subject of struggle, which only great artistes are capable of."

Faiz referred in another interview to Manto’s ‘exquisite short stories’ and went on to say "but after 1950, he lost his way. The film or newspaper people would give him a bottle of liquor and have him write whatever they wanted". None of this is to take away from the greatness of Manto which is universally acknowledged but perhaps we can stop quibbling about what relationship (if any) he had with Faiz; student, peer or fellow artist. Neither one of them is with us today but their art is, and that’s the way it should be.