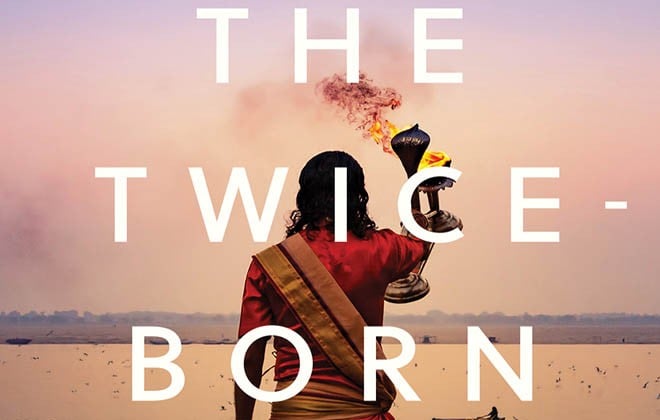

It’s rare to come across a book that delivers personal, national, and global epiphanies all at once. Aatish Taseer manages these while painting a rich backdrop of Benares

If I were ever to get a tattoo, it would be of an imagined skyline -- London entwined with Karachi (two cities I love, both which have shaped me): each individual silhouette real, but rendered a fantasy because of the impossibility of what I would make it stand beside. I thought of this when I read the first line of Aatish Taseer’s The Twice-Born: "For a long time, I had a recurring daydream of the ancient Indian city of Benares, superimposed onto the geography of New York."

I assumed the book, which is structured around Taseer’s obsession, of sorts, with Benares, would be about self-rediscovery -- about returning to one’s roots after time spent away, about finding home again as a way of untangling a hybrid identity. And it was.

But it was also about so much more -- his study of Sanskrit and the Brahmins of Benares, the 2014 election that saw Narendra Modi’s rise to power and the disgruntled young men that got swept up in it, about the long shadow of colonialism and the stubbornness of the undying caste system, about a rapidly urbanising country and an ancient city resisting its pull.

What we’re left with is something difficult to pull off: a book at the intersection of memoir and travelogue, stuffed with history, literature, and politics. The reverse journey home is common enough -- but Taseer does more than just go from New York to Delhi, he goes from Delhi to Benares, too.

"My time in the West had… grafted a layer of anxiety onto my way of looking at India," he writes. But as he points out as he makes his way to Benares by train, it isn’t just his time in New York that has made him look at his life in Delhi from the outside in: "Delhi and Benares are only eight hundred kilometers apart, but the real distance, the sense of traveling across centuries, was not physical. Distances in India rarely are."

What Taseer finds in Benares are the contrasts that define contemporary India -- a precipice between the ancient and the modern, the two constantly unsettling each other. His gorgeous descriptions of what he notices around him serve both as a respite from his reckonings and a metaphor for them: "The one image that redeemed the city was the soaring spectacle of silk-cotton trees in flower: their fleshy coral blossoms as large as fruit lay in blankets on the street, rotting in the spring sun." Elsewhere, he observes: "The air stank, and then with that Indian genius for contraries it was overwhelmed by cloying waves of jasmine."

These contrasts are more than just observations -- they are evidence for a country at war with its image of itself. And it’s a war that is playing out the world over as governments are surging to power on the back of catering to populist sentiments. The brilliance in Taseer’s writing is how he identifies his complicity in the movements that despair him. When his father Salmaan Taseer, the governor of Punjab, was gunned down by his own guard after supporting a woman accused of blasphemy, Taseer reflected: "It showed me that the isolation of people such as myself in the Indian subcontinent was not merely undesirable, it was dangerous."

Taseer doesn’t shy away from interactions that dredge up this danger. When he meets Anand, who is a "card-carrying member" of the most powerful Hindu nationalist youth organisation in the country, he strikes up a friendship of sorts. When they find themselves on a balcony overlooking the Ganges one evening, Anand points out a group of young girls in an ashram. "Anand, more than he realised, was part of the collapse of old ways. It fed his fantasies of a return to a golden age when women were pure," Taseer writes. "And the sentiment was not benign, for underlying the wish to bring back an irrevocable past was a more violent impulse to undo the present."

It’s rare to come across a book that delivers personal, national, and global epiphanies all at once. Taseer manages these while painting so rich a backdrop of Benares that I could hear the sound of bells, splash of bathers in the river. Someday I would love to see it for myself.