R.M. Naeem’s new paintings at his solo exhibition at Sanat Initiative, Karachi document a shift in his asthetics

An advertisement in the international edition of The New York Times in Pakistan carried the photograph of a model, standing against a wall, alongside a dark torso of a horse in front of another structure. The contrast between the beauty and the beast, culture and nature, glamour and raw power seemed to have disappeared in this black & white visual.

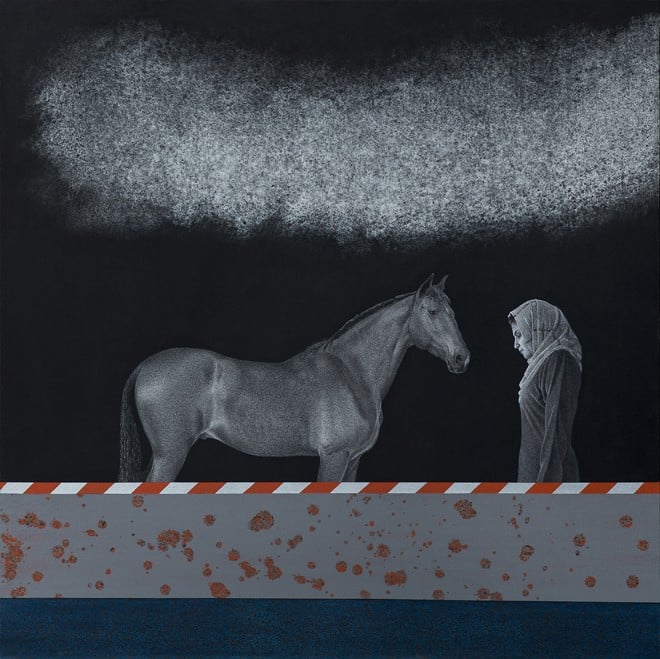

One gets the same sensation in the art of R.M. Naeem. At his solo exhibition at Sanat Initiative, Karachi from Jan 8-17, 2019, human beings, architectural settings, animals, mortals, angels, clothed and naked figures coexist in the same space; at times confrontational but mostly comfortable.

The word ‘reality’ perhaps is the key to decipher the art of R.M. Naeem, an iconic painter for many, who employs a naturalistic language to construct his imagery. His keen observation, masterly skill in rendering anatomical details, ability to create an illusion of three-dimensional mass on a flat surface with the help of brush, pencil, paint or any other tool is merely one aspect that one sees and admires. His compositions, segments that he chooses to incorporate in his canvases, his way of depicting light, constructing space and infusing elements of nature, all converge to communicate his views about the presence of a person -- in a real setting and in an imaginary world.

His new paintings (though he has been working on some of these for the past few years) document a shift in the artist’s aesthetics. Still preferring human body as the main motif, Naeem is now treating it as a vehicle -- not a cog in the complexity of content but an independent form to describe the world around us. Thus, the human figure serves as a mirror to our social, political and religious situation. References to faith (with beard and hijab), nationalism (crescent and star from the Pakistani flag in ‘Even If You Deny me I am There’), sexuality (through utensils that remind of male sex organs in ‘Submission’), and dream-like atmosphere in his work have a wider context when it comes to unravelling what we know and what we don’t about ourselves.

A recurring motif in his work is of a box, temporarily or half erect or flattened and completely open. In this group of canvases (‘Beyond’; ‘Within, Without’; ‘In The Presence Of’), box acquires a significance with reference to women -- because if a woman is sitting on its edge, a naked female is looking at her shadow on it; a man and a woman are standing on different sides while a girl is positioned against its open shape.

In Naeem’s work, the box and body present a paradoxical position -- of a woman who is not in the box. Whether it’s a box of brick and mortar or of conventions and customs, she is out of it; in some instances, she has stepped away from another box -- of clothes. Naked figures in Naeem’s painting, in essence, are nude because they are not aware of the presence of an onlooker nor they are ashamed of their naturalness. Contrary to all expectations, they are in their comfort zone, at ease with being what they are, without the interruption and inclusion of the Other.

More than the body, it is the human emotions, relation between them and their connection with the world that leads to new narratives in the art of R.M. Naeem. For instance, a woman sitting on a sofa, holding a small child in her hands is complemented with another canvas with a cartography of an identical seat amid a chaos of texture; or a woman sitting on a stool with another child at the back, or a figure enclosed in the outlines of a transparent structure underneath the small body of a child with wings. For the painter, these are not babies or cherubs or angels, but dolls; at places dismembered, representing the familiar cruel conditions.

Deciphering a painting, video installation, sculpture or performance has become a necessity among the art audience, notwithstanding that beyond decoding, it is the visual impact that forms a point of contact between the viewer and the maker. It’s a neutral ground that liberates a consumer of art from compulsions of all sorts -- content, context, commitment -- and lets them enter into a shared space, of senses, pleasure and memory.

This is what culminates in Naeem’s painting ‘In The Absence Of’ about the Original Sin. A recreation of Albrecht Durer’s engraving ‘Adam and Eve’, from 1504, around the apple tree, with Eve holding the fruit. But he has turned it into a visual of our times, reassuring that even if we live in the present, we also survive in the past, in a collective memory derived from religion, mythology or folklore.

We know that we the human beings of twenty-first century are far removed from our ancestors, yet we share the same anatomy, even though the course of representing them has been different in the art of each epoch and era. R.M. Naeem relates to this aspect which is not limited to mere depiction of human body, but to the essence of ‘humanness’.

The link between progress and primordial is explained by Carlos Fuentes when he writes that human beings may have evolved but certain acts remain archaic: like eating, love making, dying. In his work, Naeem traces that ancient history of human kind in order to know himself and to read/recognise his times. The recent work is just a step at arriving to find what, how and where we are. He leaves the biggest question -- why we are -- for the viewers because the paintings may help answer it.