Sustainable Development Goals signed by the previous government call for renewed political commitment

In the beginning of new millennium, a global social contract was signed by the comity of nations setting a 15-year development agenda naming Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) targeting extreme poverty, education, gender equality and child mortality.

Pakistan was being ruled by military when the MDG framework was signed in year 2000. Military rule continued till 2008 when democratic transition was made possible and the exiled leadership of the PPP and the PML-N returned to take part in the elections. One of the main reasons of abysmal failure in the MDGs at the point of termination in 2015 has often been cited as the lack of political ownership of MDGs framework in Pakistan.

None of the three governments in 15 years were adequately geared to integrate MDGs framework with public policy and budgetary frameworks with the exception of Benazir Income Support Programme (BISP) -- a gender-sensitive social protection initiative announced in 2008 through an act of the parliament.

Hence, Pakistan failed most of the MDG targets while countries in Sub-Saharan Africa made substantial progress in the same development agenda. In Pakistan’s context, three key factors can be attributed to the underperformance of MDGs and related development targets: (a) lack of political ownership of MDGs, (b) institutional disconnect of MDGs with multi-layered governance framework and (c) absence of and disregard of allocative and technical efficiency.

Resultantly, the official assessments revealed that out of 34 indicators, Pakistan was able to achieve only 3, was partially proceeding to achieve 7 and was completely off track on 24 indicators. During 15-year MDG regime, Pakistan produced only five reports, that too based on contentious "interim data" while the government which signed MDGs in 2000 decided to drop chapters on poverty and income distribution from the Pakistan Economic Survey in 2007, considering them "politically damaging" for the regime.

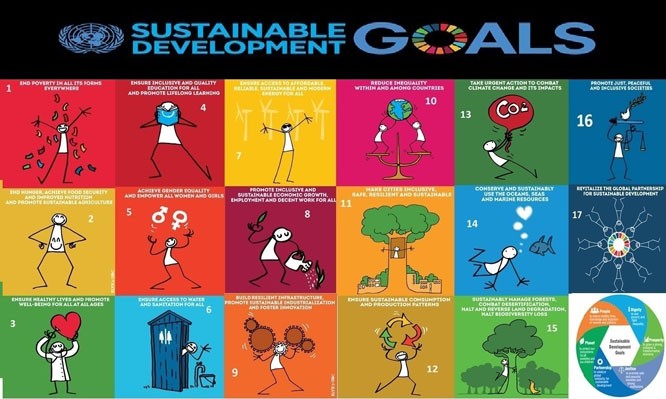

Concomitantly, there have been two civil transitions of power in Pakistan since the signing of MDGs -- in 2008 and 2013 while the latest transition of power in 2018 has just happened against the backdrop of a new global contract renamed as Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) or Agenda 2030 signed in 2015 by former PMLN-government.

This time around, the political ownership of SDGs was far more encouraging than MDGs signed by the erstwhile military ruler. For example, Pakistan was the first country to adopt SDGs 2030 agenda through a unanimous resolution of the Parliament in February 2016, making it a National Development Agenda. Some follow-up institutional and administrative mechanisms were also put in place which include forming Parliamentary Task Force on SDGs at federal and provincial levels, establishing Prime Minister’s SDG Fund and setting up SDG-Support Units at federal and provincial level on cost-sharing between respective governments and UNDP.

Meanwhile, the general election 2018 has reconfigured the power landscape in Pakistan where the PTI rules the centre, Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa while Sindh government is retained by the PPP, and Balochistan is led by Balochistan Awami Party, a relatively new entity founded in 2018 by political dissidents of the PML-N. The former ruling party, signatory to SDGs, failed to form government, however, it offers a strong opposition in the National Assembly, Senate and Punjab Assembly with an overt support of other opposition parties including rival PPP, making the government accountable at federal and provincial levels, particularly in Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa provinces.

The electoral manifestos of key political parties including PTI, PPP and PML-N make direct references to the SDGs which is a step forward at least at the level of conceptual recognition by the key political actors in the country. However, mere recognition of SDGs does not serve much without actual delivery of missing services to the people of Pakistan.

Experience has shown that development interventions have largely been decided and influenced by supply-driven and patronage-based considerations or dictated by technocentric approach in isolation of political economy paradigm.

Development is not merely a technical issue neither it is an apolitical process. SGDs cannot be achieved without some key political decisions aimed at critical public policy rethinking if not reforms per se. Development communities need to identify the political pathways through which progress towards sustainable development is possible, and to understand how the SDGs can facilitate such progress.

A renewed political commitment on SDGs is required by the government that took charge of the country after 2018 elections as the SDGs were signed by its rival political party. An uncertainty has also been created about the future of the 18thAmendment and National Finance Commission Award which could jeopardise the previous political consensus on key areas of constitutional governance including provincial autonomy, democratic devolution and fiscal decentralisation, reversing the process of democratic consolidation in the country.

Punjab, KPK and Balochistan also need to refer to the previous work done in this direction and internalise SDGs as a point of departure for short-term and long-term development planning, implementation and management. On the other hand, PPP in Sindh has reassured consistency and continuity of policy commitments on SDGs referring to its electoral manifesto. Chief Minister Sind Syed Murad Ali Shah has already identified six priority areas to be integrated into the budgetary framework of the Sindh government by realigning forthcoming annual development plans in line with the SDGs targets.

With the social sector devolved to the provinces, there is a need to develop robust inter-provincial mechanisms to mainstream SDGs in existing sectoral planning via annual development plans and long-term budgetary frameworks. Much needed ‘localisation of SDGs is possible through a decentralised political response to lingering development deficits at local and sub-national levels.