A tv serial on the centenary of Bolshevik Revolution may appear a disfiguration of Trotsky’s actual role but there is an unspoken subtext of Trotsky: the nature of Russian revolution

Leon Trotsky was literally assassinated once but figuratively murdered a number of times. In the past, his figurative assassination was the job of, what Trotsky himself called, Stalin School of Falsification. Of late, the Stalin School of Falsification has been seconded by ‘Putin School of Falsification’.

A case in point is Russian television serial, Trotsky. Originally aired on state-run Channel One in 2017 on the centenary of Bolshevik Revolution, it was a big hit in Russia. The eight-episode serial was recently released on Netflix to a global audience. Salted with anti-Semitism and peppered with eroticised sequences, Trotsky is littered with too many factual inaccuracies and historical falsifications to be documented in a newspaper review. Therefore, this article will restrict itself to only three aspects: Trotsky’s delineation, his relationship with Lenin and finally the portrayal of 1917 Revolution.

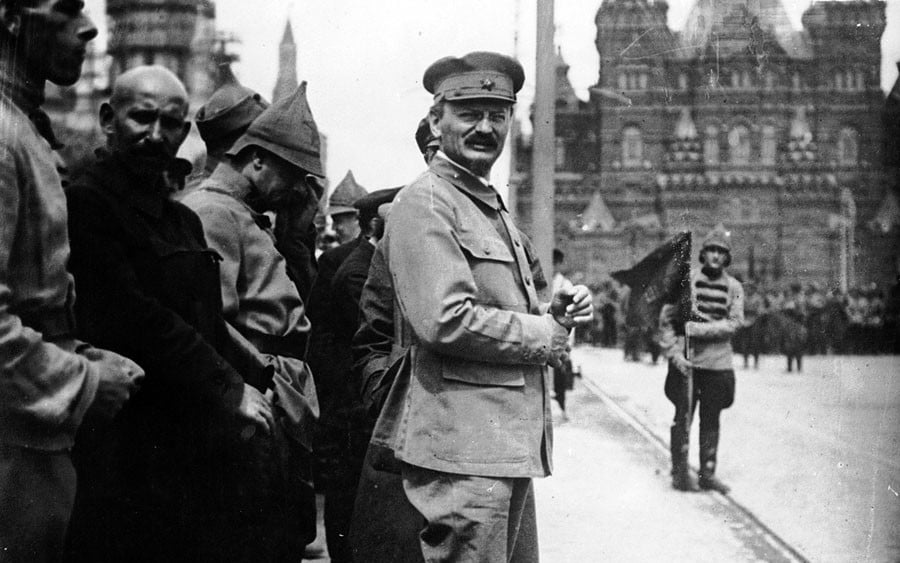

Trotsky in Trotsky (Konstantin Khabenskiy) is recognisiable only to the point of similar looks. Else, he has been depicted as a tyrant, blood-thirsty, cruel, ambitious, megalomaniac, hypocritical, devious and above all fanatical. In short, he is a Stalin-defeated, outwitted by actual Stalin in the bloody power struggle merely because he had isolated himself from the top-Bolsheviks owing to his arrogance.

In fact, in the very first episode Trotsky orders to shoot down every tenth soldier in a military unit that had retreated, instead of fighting the White Army, from a front.

In yet another sequence, Trotsky’s armoured train runs out of fuel in the middle of all-ice Russian wilderness. Incidentally, the train had halted next to a cemetery. Trotsky orders to burn the wooden crosses erected over every grave in order to provide for coal. Meantime, a funeral arrives and the villagers protest over the desecration of graves. Every agitator, including women, is gunned down as an unmoved Trotsky coyly looks on. A number of such atrocities have been portrayed to establish Trotsky as the architect of ‘Red Terror’.

Throughout the eight-episode serial, Trotsky defends Red Terror that did not spare even deposed Tsar, Tsarina and their innocent children (A British documentary also released in 2017, The Russian Revolution [Dir: Cal Seville] blames Lenin for the shocking murder of Romanovs in order to avenge his elder brother’s execution).

Trotsky restored capital punishment. Organised show trials (episode 7). At times, Trotsky sounds like Pol Pot, ready to consign millions to death in order to push history forward. For instance, Trotsky justifies Kronstadt massacre (episode).

His cruelty is pathological. He is cruel to his own children. He goes for a secret meeting with Lenin (to grab power in October 1917) instead of rescuing his daughters stranded inside a meeting-hall that catches fire. Hardly a novelty that such a person is not faithful to his wife. In fact, the film opens with an exotic scene depicting Trotsky in bed with his young secretary (she was an anarchist before the Revolution and married to a loyal Bolshevik). He unscrupulously ditches his first wife, leaving her behind in Russia, and starts living with the second, Natalya (Olga Sutulova) during his exile in Europe. And of course, Natalya is betrayed when Trotsky meets Frida Kalo (Viktoriya Poltirak). However, he plots the murder of Markin (Artyom Bystrov), Natalya’s lover. Trotsky was jealous of Markin not merely because the latter fancied Natalia. Markin had to be eliminated also because he had helped Trotsky when Trotsky was weak and Markin’s presence undermined Trotsky’s aura as commander of the Red Army.

Above delineated devious and treacherous, Trotsky meets his equivalent in the person of Lenin (Evgeniy Stychkin). From their first meeting in London onwards, they are scheming against each other. They are envious and jealous of each other (Here, Stalin School of Falsification connives with Putin School of Falsification). In one absurd scene, Lenin even physically bullies Trotsky. At the Brussels congress in 1903, Lenin manoeuvres to stop Trotsky from speaking till Trotsky agrees to utter whatever Lenin dictates. However, Trotsky in turn cheats Lenin and is finally expelled from the party.

They meet again only after the February Revolution. Again, both begin to plot against each other. While Lenin hypocritically and cleverly welcomes Trotsky back in the Bolshevik faction, he is not allowed in the leadership role. However, thanks to Markin (mentioned above) and his bullying tactics, Trotsky does not merely reaches atop party hierarchy, he even seizes the opportunity to marginalise and discredit Lenin once Lenin goes into hiding during July 1917.

Trotsky makes fun of Lenin’s cowardice: ‘Lenin hides in a safe house and writes letters’ (episode 5). In fact, Trotsky even violates Lenin’s instruction regarding armed insurrection. Instead of October 27, a self-centred Trotsky initiated insurrection on October 25, his birthday. Lenin, in turn, accuses Trotsky of conspiracy to replace him as the party head.

Trotsky would have completely edged Lenin out of Bolshevik leadership had not Lenin played the anti-Semitism card against Trotsky. Russians, Lenin tells Trotsky on the eve of October insurrection, would never accept a Jew as their leader. He could only be second-in-command, Lenin suggests. Reluctantly, Trotsky relents by cursing: ‘Go to hell Comrade Lenin’.

Post-revolution, despite the mutual hatred, both accept each other as necessary evil for the sake of power and respective personal ambitions. After all, both wanted to spearhead the revolution. While Stalin (Orkhan Abulov) is shown on the side of Lenin in the Lenin-Trotsky disputes, Lenin had a change of heart after he is struck by paralysis months before his death. Lenin finds Stalin rude and unfit to lead the revolution. Despite his dislike for Trotsky, Lenin considers him an able successor. Hence, builds a block with Trotsky to remove Stalin from the party leadership. But before this plan translates into any concrete action, Lenin dies and his will is suppressed by Stalin.

Certain similarities between the two have also been demonstrated. While Lenin considers people an instrument to unleash revolution, Trotsky considers people merely a material in the process of history. Both are fanatical, pragmatic, and ambitious.

While the above depiction -- ridiculous as it is, may appear a disfiguration of Trotsky’s actual role, there is an unspoken subtext of Trotsky: the nature of Russian revolution.

It is on the point of Russian revolution that the Putin School of Falsification departs from the Stalin School of Falsification. Trotsky portrays the revolution as a coup, a conspiracy successful only because of Trotsky’s armed insurrection.

In fact, the Russian revolution was bankrolled by European Jews. Revolution’s isolation is depicted in a satirical scene: Trotsky orders to arrange a mass public meeting in 1921 to declare his victory over the White Army. However, a handful of scarred women and children ‘arranged’ for the rally were held in audience at gun point. An embarrassed Trotsky leaves the podium without exhibiting his skills of oration.

By portraying the Russian revolution as a coup, a Jewish conspiracy, hopelessly unpopular and brutal which only replaced Tsardom with concentration camps, purges, massacres, Red Terror, and hunger, Trotsky depicts Putin regime’s uneasy relationship with the USSR. Putin wants to play the role of Stalin’s successor. However, he does not associate with revolutionary energies unleashed by the Bolshevik revolution. Not a coincidence that Revolution’s centenary met with an official silence in Putin’s Russia. But victory over Fascism is celebrated, with fanfare every year.