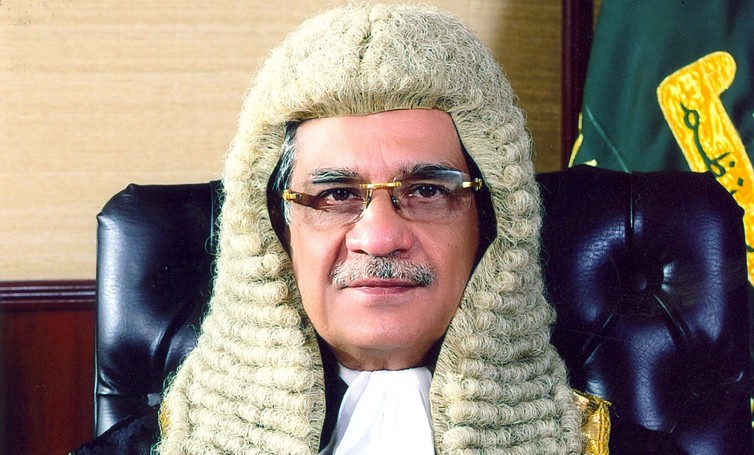

Justice Saqib Nisar’s attempt to clean up the vast stables of a faltering state has revived the debate on the limits to judicial and legal correctives to socio-political ills

As the greatest exponent so far of judicial activism in Pakistan and for his big strides along the populist path, the outgoing chief justice of Pakistan has surely earned a place in the history of this country, though how exactly history will judge him only time will tell. Justice Saqib Nisar chose not only to stop the movement away from the Iftikhar Chaudhry court’s assumptions and practices, he also resurrected them and built extensively on them.

He went for politicians suspected of corruption with the zeal of a missionary and gained popularity, though the net result of his exertions in this area ran parallel to other forces’ drive to target two mainstream political parties in particular and raised questions about their impact on the country’s democratic future.

He also dealt firmly with the administration’s fads and foibles, coming down heavily on state functionaries who deviated from rules, caused the state loss of money or prestige, and tried to regulate their conduct in the interest of the state and the people.

He will be remembered for reducing the distance between the court and the humblest of seekers of justice and relief. To be able to address the issues raised by citizens at the various registries, he not only worked on holidays -- and persuaded brother judges and members of the bar to keep pace with him.

He earned a great deal of goodwill by his choice of matters for intervention: free exploitation of groundwater resources by bottlers of water for drinking, the excesses committed by cement manufacturers near Katas temple complex, the escalating school fees, and the rising mountains of garbage in Karachi, et al.

His extraordinary interest in retrieving state land from the possession of qabza groups paid dividends to the state and himself though the demolition of shops and houses of the beneficiaries of official actions did not fail to raise questions of equity and even-handiness.

Finally, Justice Saqib Nisar launched a campaign to build two dams to conserve and better utilise the country’s dwindling water resources that the prime minister also joined.

How will all these initiatives be judged by independent evaluators in future?

That these actions amounted to symptomatic treatment of the malaise that has been eating into the vitals of the polity could not be denied. Any evaluator is likely to raise some basic questions at the very outset. Firstly, whether the court should have assumed the role of the executive in deciding matters to the minutest detail -- such as the price of the land required by a privileged developer -- or whether it should have compelled the authorities concerned to do their job.

Connected with this question is the second question of the continuity of the CJ’s measures. Since no institutional change has taken place, what is the guarantee that the system has been cured of the disease or that the process of recovery has begun? True, the corrupt state functionaries received a warning that they could be caught and made to pay for their misdeeds. The gamblers among them might blame their fallen colleagues for their lack of expertise in covering up their tracks. Moreover, bribery and favouritism are only some of the maladies the system is suffering from. Attack on them does not necessarily make the state employees efficient and diligent.

Justice Saqib Nisar’s attempt to clean up the vast stables of a faltering state has revived the debate on the limits to judicial and legal correctives to socio-political ills. If Pakistan’s problems are rooted in the feudal culture and the consequences of adopting the principle of dual sovereignty, can these problems be resolved through court decrees? How do we persuade a person who swears by divine injunctions to abide by the state’s laws?

Justice Saqib Nisar took judicial populism several notches beyond the point reached by Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry. Naturally, public expectations about the judiciary’s capacity to heal all the festering sores also soared by the same token.

The people had reason to hope that the CJP would be able to free the state of the bar to land reform placed by the Shariat Appellate Bench under a questionable interpretation of Islamic law. Abid Hasan Minto’s petition of 2011 against that verdict was decided neither by Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry nor by Justice Saqib Nisar. Nor was it possible for the CJP to listen to the wails of the tillers of the land wrongly occupied by service entrepreneurs in Okara and Khanewal.

Similarly, when Justice Saqib Nisar eloquently put human rights at the top of the Supreme Court’s agenda, there was a spurt in the hope for justice for the detainees at the internment centres established under Actions in Aid of Civil Power Regulation, 2011, for FATA and the victims of enforced disappearance. It would have been much better if these issues, too, had received a passionate response from the CJ. It is not easy to dismiss the thought that there could be no-go areas even for the heads of the apex court, however strong they were in imposing their writ on the other organs of the state.

A question that has received relatively little attention relates to the evolution of the apex court as a body pushed along by a strong leader or as an institution wedded to decisions by consensus. The common interest of the members of the superior judiciary is known but one should like to be reassured of their capacity for tolerating dissent within.

Also read: "Effective self-accountability is a disproven myth"

The immediate successors to Justice Iftikhar Chaudhry perhaps realised the unwholesome impact of inflated activism on the normal functioning of the SC and rediscovered the golden principle of judicial restraint. The successors of Justice Saqib Nisar may also have to strike a balance between the apex court’s primary responsibilities and the lure of judicial activism/populism.

Justice Saqib Nisar increased his credit by admitting the urgency of judicial reform and his inability to carry it out. He could not have completed the task even if he had tried. But this issue needs to be kept on the joint agenda of all the three state organs. May be, it is time to renew discussion on the creation of a separate court to tackle constitutional issues and matters concerning federating units’ relations with the federation or with issues of common interest. At the same time, the discovery of administration’s malfunctioning on a large scale has drawn attention to the possibility of creating an administrative court that may deal with both systemic disorders and matters at present assigned to service tribunals.