She was not part of any political, social, literary or even feminist movement. There was nothing glitzier in Khalida Hussain’s life except her fiction which defies boundaries

Great souls die and

our reality, bound to

them takes leave of us.

-- Maya Angelou

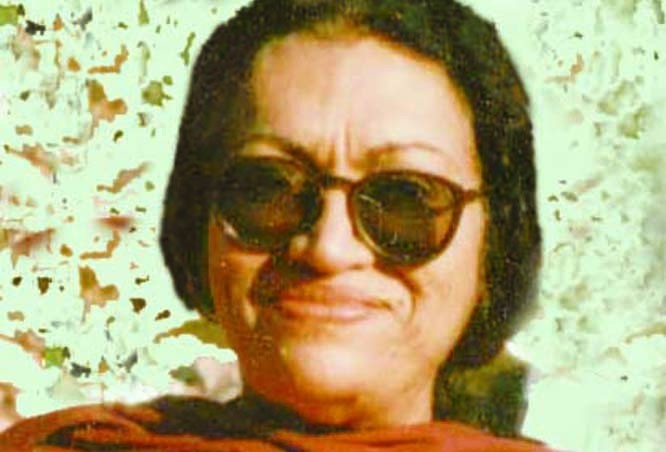

Another great soul left us on the cold, cruel morning of January 11, 2019, for her eternal abode. It’s a pity that our reality bound to Khalida Hussain’s person abandoned us forever. Yet, there is solace in the fact that the reality she created in the form of six collections of short stories and a novel exists with us and will keep reminding us of a great and compassionate soul.

There was nothing glitzier in Khalida Hussain’s life except her writings. In a sort of stoicism, silence and seclusion, she seemed to have discovered what comprises the greatness of soul. Born in Lahore on July 18, 1938, she moved to Islamabad after marriage, then Karachi and returned to Islamabad where she lived till her last breath.

A tiny, unusual event occurred in her life when she had to suspend writing for almost fifteen years. It was a notorious writer’s block that might be attributed to her marital life, but she didn’t ascribe it to the decay associated with married women in patriarchal societies. She did not write her autobiography nor did she join any political, social, literary or even feminist movement. She was used to staying aloof from literary gatherings. She did not express a point of view on any issue big or small and hence courted no controversy. There was no hullabaloo about her that is the hallmark of many feminist writers. The only shocking event that she couldn’t avoid was the death of her young son, leaving her devastated.

Hussain’s stories are devoid of common feminist themes. Though her stories revolve around exploring and interrogating the dark side of self, she doesn’t situate self within a feminine ambience. She doesn’t consciously escape femininity; rather she seems to cuddle a genderless, human self. This way she took a path distinct from the one taken by her predecessors and contemporary women writers.

She appears to emphasise that there exists a ‘continent’ within the being or wajood of humans that remains unaffected by gender-based identities and confinements. She made her male and female characters discover that ‘continent’, reside there, breathe there, imbibe its ambience so that they could interrogate everything surrounding them from an ‘immeasurable’ perspective. All her six collections of short stories -- Pahchan (1981), Darwaza (1984), Masroof Aurat (1989), Hain Khaab Main Hunooz (1995), Main Yahan Hoon (2005) and Jeenay ki Pabandi (2017) -- and a novel Kaghazi Ghat (2005) tell the story of human self.

In a way, she subscribed to the Naya Urdu Afsana that emerged in the early years of 1960s, marked by a revolt against the social and socialist realism that began in the early decades of 20th century, reached its climax in the 1930s with the advent of progressive movement and continued, with a few exceptions, throughout the decade of 1950 as well. Naya Urdu Afsana, also branded as symbolic (alamti), was bent on experimenting and devising new techniques of narrating a story in a bid to capture the ‘fragmented, alienated self’ being experienced by persons living in an urbanised, industrialising, suppressed society on the one hand and encountering displacement, disintegration and migration on the other.

A study of existentialist writers, new psychological theories and myths of the world helped the writers of Naya Urdu Afsana in fabricating their narrative style, plot, characterisation and settings. On the surface, it was non-political but underneath had political overtones.

In the earlier stories of Khalida Hussain, we detect some conspicuous traces of Intizar Husain’s style. It was characterised by magical realism, though of its own kind, and also a consistent struggle against moral and spiritual crisis. Soon she discovered and trod on her own path. ‘Savari’ (ride), one of her best pieces, tells the story of how a young writer succeeds in outgrowing the appetite for being in other’s shoes. In this story images -- of three unknown men, cart, twilight, bridge of river Ravi and a queer odour -- become pregnant with multiple meanings.

Her fiction defies boundaries. While reading her stories, you fail to differentiate between the narration of event and depiction of feeling. Difference of event and feeling is also blurred. This is not just a play of two, mutually exclusive worlds; rather it is a way of creating an existential moment where a collusion of society and self, rationality and sub-consciousness, realism and surrealism occurs. Collusion, yes. The old feud between mind and body, simple sensuous perception and ‘pure rational knowledge’ and archetypal division between things and words form the basic themes of many a story.

The most significant trait of her stories is that big, basic human questions have been dealt through small, simple, ordinary events of life. This way she raises the fundamental human problem of seeking immortality through mortal, perishable things.

Dr M Ajmal precisely identified in her stories ‘subjective objectivity’ (Dakhli Kharjiat), meaning she doesn’t escape the objective world; instead ensnares it by her subjective world or wajood (existence). She doesn’t seem to base her notion of wajood on any philosophical theory. To her wajood is what we encounter in our ordinary, daily happenings, surrounded by small, usual, everyday things at a particular moment. As no political or social turbulences are there to grid the characters of her stories and administering their responses, her stories ostensibly appear simplistic and naïve.

In reality, her fiction decentres the centrality of outer world being consistently manufactured by others, alien to human self, to human desires, to the authentic experience of human self. Human wajood is fenced by things, friends and foes, small daily happenings and of course time. The narrator of ‘Zawal Pasand Aurat’ mourns the death of a fly and sorrowfully thinks about the existential difference between the fly and herself, though there does exist a point where the destiny of fly and human beings meet. Jurist of the city issues a charge-sheet against her because while there prevailed a national crisis, she was thinking about a fly. Here, Hussain seems to respond to her critics and also tries to show that reflection on the death of even a tiny creature can lay bare the abyss of destiny that we all -- big creatures or small -- have to embrace after all.

How the small, ordinary things are existentially pregnant with big, fundamental meanings is the hallmark of Hussain’s fiction. In some stories, she symbolises everyday things to convey grand meanings; in others, she creates a pure fictional ambience inundated with both intimate and unkind relations between people and things. ‘Masroof Aurat’ and ‘Adhi Aurat’ can be mentioned in this regard. Aurat of these stories doesn’t represent a woman shattered by patriarchy but devastated by being terribly conscious of the divide between anima and animus, persona and true personality, grand ideals and real ordinary perception. Her protagonists (men and women alike) are all the time engaged in an unrelenting search for a ‘place or ground’ where they could reside with their true, genuine, single self but fail.

In Main Yahan Hoon, Darwaza and Jeenay ki Pabandi, her protagonists experience a continued process of fragmentation of self. There is no exit, no emancipation, no single reality, no single version of reality and no ‘place’. She doesn’t refer to any hell, but appears to be saying that we are bound to live in a prison-like house with a fragmented self.

In some stories, Hussain seems to outstrip the ordinariness of things in a bit complex way. The narrator and protagonist of ‘Hazaar Paya’ discovers that things are real while their names cause duality. He starts collecting the names of all things that he ever came across. As he finishes writing down all names, he discovers shockingly that they have been erased from his memory. Where did they actually exist? On paper or in his memory? In their thingness or in their names? Spotting the dual character of existence of things baffles him; he who is already suffering from a cancerous disease, he swaps the ordinariness of things for mafhoom-e mahz, absolute, unadulterated, mysterious, authentic meaning of them.

The same theme once again appears in ‘Jeenay ki Pabandi’ though in a less complex manner. The search for mafhoom-e mahz is tinged with the postmodern way of writing fiction.

The writer is a Lahore-based critic, short story writer and author of Urdu Adab ki Tashkeel-i-Jadid (criticism) and Rakh Say Likhi Gai Kitab (short stories)