Whenever I think of Akbar Masoom and his poetry, I don’t remind myself of moral strength or fortitude. I think only about creative urgency. What remarkable stamina to express himself in poetry that seems to make a mockery of physical infirmity. Here is a sensibility unburdened with care, punctuated by lyrical outbursts.

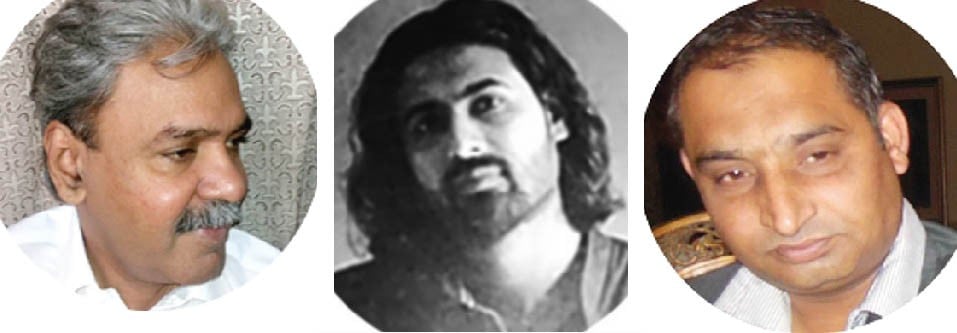

The reader can ask, with reason, what am I talking about. Akbar’s life is a disturbing accumulation of disorders. He was born in Sanghar in 1961. Not in a fit condition even as a child, a medical checkup in 1989 revealed that he suffered from proximal myopathy, a disease for which, the doctors said, there was no cure. As if it was not enough of a tragedy, five years later, he contracted tuberculosis and could no longer hear, speak, see or taste. A complicated surgery restored him to a modicum of well-being. Confined to a wheelchair, and earning his livelihood by working as a homeopath, he has not given in or given up.

I write this not to evoke sympathy for him. He doesn’t need it. He is made of sterner stuff. What surprises and delights me is his poetry. In my gloomier moments sometimes I have looked askance at poetry and its presumed efficacy. But when I came across Akbar’s first collection of ghazals, entitled Aur Kahan Tuk Jana Hey I said to myself: "How marvellous is poetry, making a nonsense of physical infirmities."

I was overwhelmed not by the fact that he wrote ghazals, there are already too many who do so, but by the realisation that his ghazals were uncommonly good. I was not alone in being astonished. Javed Shaheen, a very fine poet himself, after reading some of Akbar’s ghazals, said: "What a talent!"

His second collection, Baysakhta appeared recently. There is no falling off at all. The best ghazals sparkle, as if something newly minted. They are, in turn, exclamations of wonder, a toned down sadness, a penumbral, shadowy appearance. Everything that we associate with ghazal’s essence is here. What more can you demand of a poet who has transformed adversity into an unreserved longing for life and love. The most elegant thing in the book is a quasi-ghazal written to celebrate the marriage of a friend. It deviates from the formal diction of the ghazal with a modality and lilt of its own.

With Ahmad Ata’s first collection of ghazals, Ankh Bhar Tamasha Hey, we cross over to a different sensibility. Although ghazal, as a genre, imposes its dictates on each of its practitioners, there are always discreet divergences which can’t be ignored. Unlike Akbar Masoom, whose gazals generally reveal the disturbing realities of life, Ata’s lines are often close to everyday speech and the radeefs and rhymes are unobtrusive. He is also lucky in the sense that his work has been looked at with approval by two leading Urdu critics. Shamsur Rahman Faruqi, who has contributed an introduction, says: "Here and there in Ata’s work cynicism and mistrust can be noticed, an attitude of evident estrangement (and a private anger and dislike) which should be regarded as an attempt to restore to the ghazal its former vast reaches." On the other hand, Shamim Hanfi remarks: "In Ahmad Ata’s ghazals the element of spontaneity and newness is to a large extent a manifestation of raw sensibility."

There seems no need to dispute these views which, notwithstanding the references to cynicism and a sensibility in the making, seem encouraging enough. Ata’s tone, as I said above, possesses a colloquial directness. Only in one ghazal, which is dedicated to Afzal Ahmad Syed, whose poetry aims to reach a state of convoluted brilliance, does he try his hand at contrivance. A conscious effort perhaps to write something closer to Afzal’s mannerism.

The poetic experience here rests primarily, with subtleness, on a fusion of feeling and emotion. Some unevenness of expression is also in evidence, indicating that his control of language is, at times, not compelling enough; a shortcoming which he will, if he retains his seriousness, overcome by and by. Faruqi says: "Sometimes it is hard to understand whether the poet is making fun of us or laughing at himself." If there is a cynic in the shadow he is probably looking at the world with distaste and bitterness which can only end in an incomprehensible chuckle.

Kashif Husain Ghair in his collection of ghazals entitled Kahan Jaye Gee Tanhayi Hamari has little in common with Akbar or Ata. It is yet another testimony to the ghazal’s strange and mystifying diversity.

Of the three he is nearest to the classical mode, with the rider that his work nonetheless mirrors what is immediate. On the surface the diction stays fairly close to what we expect from the ghazal. Below the surface or behind the typical words, there is a world on the edge of disaster and an alienation which lies in ambush.

The sense that things alter around us prevails strongly and the incessantly changing prospect sets in motion a sensation which saps one’s resolve. The diction underscores the sense of disenchantment and fragility of relations. Conventions of ghazal act as a screen, censoring out one’s individuality. The ghazal is adept at keeping off autobiographical elements. We come across, again and again, the unadorned essence of ghazal’s concerns. The cosmetic accessories, once relished, are gone. In Kashif’s poetry we face the constant, frenetic pressures of our times. He has found a very vocal advocate in Shamim Hanfi who says in his preface to the book that Kashif is a man in search of the unforeseen. According to him, "the distinctive feature of Kashif Husain Ghair’s poetry is that all his senses remain alert when he writes. He is not merely a poet. He could have been anyone -- a painter, sculptor, storyteller, magician, or a musician." High praise indeed. However, it should be kept in mind he wanted to be a poet. It is the only discipline to which his creative energy could yield.

A lonely man who sets out on a lonely journey which is as much outward as it is inward. That is what Kashif says or implies. Poetry is loneliness personified, given a habitat and a name. Someone said: "A lonely man is God’s neighbour."