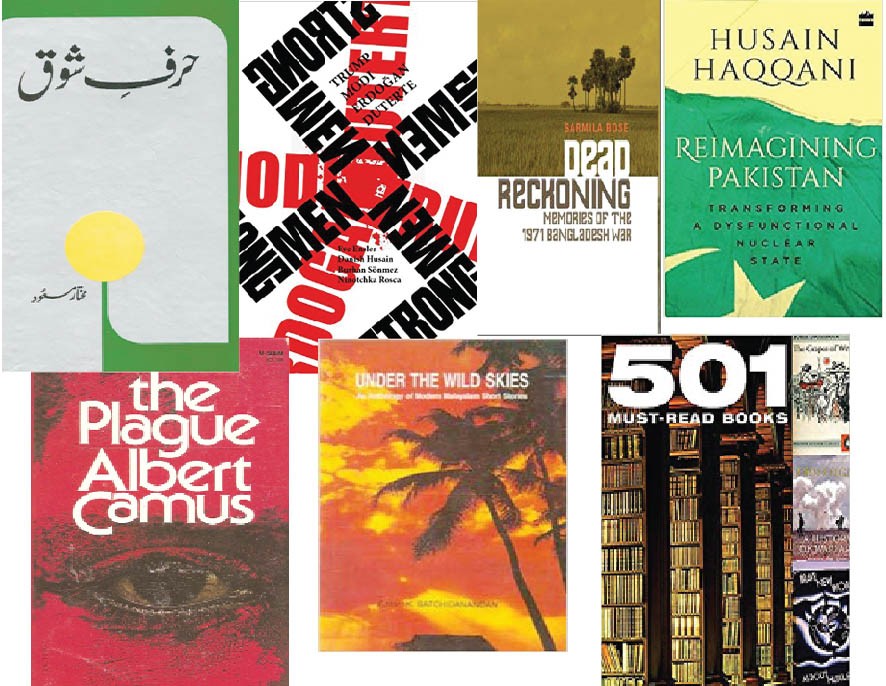

TNS asks avid readers from different backgrounds about one book they read in 2018 that left a mark on them. Here’s the list…

Absurdity of human life

Ammara Maqsood

I am cheating because I actually read Albert Camus’ The Plague more than a year ago but I have not read anything since that has stayed with me in the same way. I picked up a copy on a whim -- my leisure reading taste runs more towards detective and espionage novels -- and only started on it when I had nothing else to read on a long-haul flight. More than anything else, I was caught by the beauty of the prose. I read an English translation, probably a pale comparison to the original French, but found the prose both simple and compelling.

There is a starkness in Camus’ descriptions, mixed in with more lyrical passages; I was very much taken in by his references to and passages on the sea that forms the backdrop to the plague-struck city of Oran. I feel that sometimes we ruin the pleasure of reading by our emphasis on the meaning and philosophy behind the writing. In my opinion, it is in the enjoyment and experience of reading itself that we begin to appreciate the meaning behind the writing and make it our own.

So, I will not say much on Camus’ larger absurdist philosophy other than that the theme of human suffering is central to the book. But Camus makes no virtue out of bearing it or alleviating it, even as the characters in the novel try their level best to take care of others around them. For Camus, this is all just part of the absurdity of human life, and there is nothing else to do but live it.

The writer is Lecturer in Social Anthropology at

University College London. She is the author of The New Pakistani Middle Class (Harvard University Press, 2017)

Pen pictures from the past

Dr Khawaja Muhammad Zakariya

Of the books I read this year. I enjoyed Mukhtar Masood’s Harf-e-Shauq the most. Although published in September 2017 I got to read it this year, and it engaged me with the liveliness of its Aligarh tales, philosophical reflections and assorted musings that capture nearly a century of the subcontinent’s social history. Masood retired as a federal secretary in the Pakistani civil services but like many bureaucrats, also carried a flame for literary pursuits and recognition.

He established himself as a writer of distinction right from his first book Awaz-e-Dost in 1973, after which he published Safar Naseeb in 1981 and Loh-e-Ayyam in 1996, all of which were critically praised as well as widely read. However, Harf-e-Shauq, his swan song, is distinctive for eschewing his more ornate earlier style and moving into the territory of natural prose that captures Aligarh city, the university campus and related well-known personalities in pen-pictures that are both moving and real. Prominent people spanning a whole century belonging to diverse classes and religions come alive on the page. A cast of principled, goal-oriented and wise men and women working to make Aligarh the most remarkable institution of its time, a place where he learnt a worldview that was new to Muslims: a privileging of rationality over emotionalism.

Masood did not just identify with this worldview theoretically but also applied practically to his life. It is also here that he learnt critical thinking and independent judgement of mind -- all facets of his personality that make his writing compelling.

It now seems almost a matter of surprise that only a few years ago we had people like Mukhtar Masood who read and acquired knowledge in the English language, dealt with official affairs in English but when they wrote Urdu they did so with such crispness and authority that not even a shadow of one language crept into the other. This book, in particular, has well-crafted Urdu prose that retains a natural ring, managing to evade affectedness.

The writer is Professor Emeritus University of the Punjab

Of political populism

By Harris Khalique

We witness the forces of bigotry and deception riding the wave of political populism across the world. There is a return to an acceptance of misogyny and racism in the wider public imagination. Democratic rights and the freedoms of association and expression are being subdued. While there is analysis offered by some academics to understand populism of our times, it was inventive of Vijay Prashad to ask four artistes to comment on the populist men who rule their respective countries.

Prashad compiled and edited Strongmen containing four essays and an insightful introduction penned by him. He presents an analogy between the rise of fascism in the twentieth century and the rise of populism today. This populism builds itself around the rhetoric of protectionism, curbing corruption, and social service provision. But the real policies and practice contradict this rhetoric.

The essays in this book establish once again that genuine art and authoritarian politics seldom reconcile. Besides, the artists and creative writers have a different lens from the ones used by both journalists and academics to view society, politics and history.

The feminist American playwright Eve Ensler writes on the US President Donald Trump, Indian actor and storyteller Danish Husain on the Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, Turkish novelist Burhan Sonmez on Recep Tayyip Erdogan, and Filipina journalist and fiction writer Ninotchka Rosca on the President of Philippines Rodrigo Duterte. In the case of Pakistan, Prime Minister Imran Khan’s populism can be compared with these men only to an extent. Because unlike the control enjoyed by the four men discussed in the book, Khan is overseen by the permanent institutions of the state who had facilitated his rise.

The writer is a poet and essayist

A sharp spectacle

By Masooma Syed

It was in the latter part of the year that I got this book Under the Wild Skies as a present from a friend in Delhi. The book of modern Malayalam short stories, edited by K. Sachidanandan is published by the National Book Trust, India. It covers hundred years of fiction writing by many great Malayalam writers from Kerala.

The range of stories is wide and vast with a distinct expression by each writer, telling a unique tale of their land and people. I was amazed by the variety and intensity of the subject matter and how eloquently these stories have been told. Some stories are stark, intense and poignant, others are full of clever humour about the nuances of communism and matriarchal societies in the history of Kerala.

Stories of writers like NS Madhavan, Paul Zacharia and Kamla Das, carry social-political sharpness and critical commentary on the society of Kerala and India at large. The book generously gives a panoramic view of the long history of Arab traders, Portuguese, Dutch and British rules as well as the cultural peculiarities of Hindus, Muslims and Syrian Christians living in Kerala for centuries.

Under the Wild Skies is dedicated to my all-time favourite writer, the giant of Malayalam literature Vaikom Muhammad Basheer. His story ‘The World-Renowned Nose’ is a brilliant satire piece on society and deals with complex ideas like the psychology of the masses and people anywhere that are trapped in lives not easy to comprehend -- even by themselves. Its multiple narratives in simple diction deal with the cruel paradox of life, that made me laugh and think for days.

‘Sixth Finger’ by Anand is another story that made me read it twice. A story set in Mughal India, it reveals the irrational violence that has always accompanied power. The representation of the characters of Humayun and his insignificant soldier Ali Dost is highly visual. Anand creates a sharp spectacle to history without oversimplification or moral endings.

The writer is a celebrated artist who currently lives between Lahore and Colombo

Bitter realities

Shahzeb Jillani

Husain Haqqani may be Pakistan’s most controversial dissident in exile, but he is also arguably its most influential. Conservative hardliners allied to the Pakistani army denounce him as a traitor. Liberals who generally agree with his analysis also tend to be suspicious of his intentions. And yet, very few of his staunch critics at home take the trouble to read his books on Pakistan.

His last book Reimagining Pakistan: Transforming a Dysfunctional Nuclear State came out at a time when Pakistan’s drift towards authoritarianism was being consolidated by an engineered election, curbs on media and victimisation of political opponents. Haqqani’s book offers a reality check of why we seem to be stuck in this political and economic cycle of despair.

For one, quality of leadership is a serious issue. Having once closely worked with rival Pakistani civil-military leaders, Haqqani knows what he’s talking about. He is hated by the hardliners precisely because he was an insider and one of them. But he has since come a long way and as a scholar, Haqqani shows there are structural, historic and institutional reasons why Pakistan suffers from paranoia and insecurity and seeks refuge in an ideology based on an intolerant version of Islam and maintaining hostility with India. He backs his thesis with hard facts, and a series of inconvenient truths Pakistanis are taught to overlook. For example, Haqqani reminds us that "unlike other countries which raised an army to meet a threat, Pakistan had to create a threat to meet the size of its army."

While the book offers a coherent and clear counter-narrative to the "official national security myths" about Pakistan, it also dares to offer an alternative vision for the country. Pakistan doesn’t need to justify its existence anymore, says Haqqani. It is a reality. Most people who live in Pakistan are Pakistanis by birth and "not because our forebears resolved to create an Islamic state".

For that reason, he argues, Pakistan does not need to patronise militant groups against its neighbours. It can learn to live at peace with itself and its neighbours so that it can invest more in its people, rather than military hardware.

Given how Nawaz Sharif’s third term in office was aborted, it’s a vision no political party appears ready to champion publicly. In writing this book, Haqqani’s best hope is to encourage an intellectual and academic discussion for a more inclusive, democratic and multiethnic Pakistan, even if it comes at the cost of being vilified by sinister propaganda machinery.

The writer is a senior journalist and former BBC editor

A riveting selection

By Syed Kashif Raza

Tolstoy had asked, "how much land does a man need?" I often ask myself how many books can I read. Ever since my childhood, I’ve been surrounded by books. In the best of times, I could only read two per week. This makes a meagre count of some 100 books in a year and 1,000 in ten years.

Getting a book used to be a problem, but not anymore. Now, it is more difficult for me to decide which books to read and which to leave. The best book that I read this year was a book about books 501 Must-Read Books; one that helped me deal with the problem of choice.

501 Must-Read Books provides a one-page review of books carefully selected by Emma Beare, along with a picture of the title or writer. The genres included are children’s fiction, classical fiction, histories, biographies, modern fiction, science fiction, thrillers and travelogues. The reviews, mostly, do not spoil the plot lines but we do get to know about the themes, both primary and subterranean, along with the general scheme and structure of the book. The reviews of science fiction books were particularly inspiring for me as I had never been an avid reader of science fiction. I would definitely like to read the likes of Douglas Adams now.

The book helped me make a new list of books which I would like to read next year. Foremost on my list is A Golden Notebook by Doris Lessing as it presents a female protagonist living a quartile (four-fold) life and recording it in four separate notebooks. After reading the riveting reviews, I would also like to explore more of Philip Pullman, Paul Auster, Primo Levi, William Gibson, Richard Matheson and Peter Hoeg, to mention just a few whom I have never read before.

The book also reminded me of how great an experience it was to read Tolstoy, Kundera and Borges, and that I should re-read them more often. If you’re having trouble deciding about books you must lay your hands on next year, this book about books is an answer for you!

The reviewer is a poet and fiction writer. His first novel Char Darvesh aur Aik Katchwa was published recently by Maktaba-e-Daniyal, Karachi

A fresh perspective

By Asad Umar

My most memorable read of 2018 was Dead Reckoning: Memories of the 1971 Bangladesh War, a personal narrative by Sarmila Bose. The book, which is about the 1971 East Pakistan debacle, completely dispels the propaganda created by India and the Western world against Pakistan. The writer doesn’t come from any ordinary Indian family; she is the granddaughter of Subhas Chandra Bose, a nationalist whose defiant patriotism made him a hero in India.

It is worth remembering that a woman with this family background has exposed India and others negatively propagating against Pakistan. The book recalls memories of those on the opposing sides of the conflict. It challenges assumptions about the East Pakistan conflict and exposes the ways in which the 1971 conflict has been played around pointing all fingers at Pakistan.

Dead Reckoning completely changes the perspective about the creation of Bangladesh. Bose has put the facts together impartially, without any bias and has shown rationality exposing all false claims and exaggerated figures about the death toll. Bose’s book, so far, is the best account of the 1971 debacle. Every Pakistani should read this book; rather, it should be translated into Urdu to narrate one of the greatest accounts about the East-Pakistan debacle, to the people of Pakistan.

The writer is a

Pakistani politician who is the current Federal Minister for Finance, Revenue and Economic Affairs