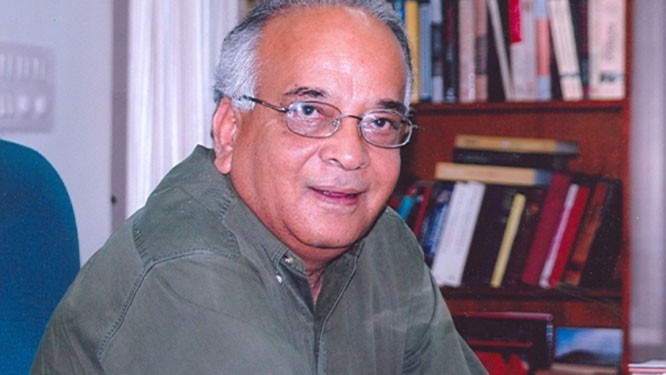

Mushirul Hasan was indeed a class apart

Mushirul Hasan’s sudden demise has left a saddening effect on the fraternity of South Asian historians. He maintained poor health for the last couple of years, ever since he had a road accident and was confined to bed. But things became ominous when his kidneys started malfunctioning. He was put on dialysis followed by other complications, and on Dec 10, 2018, the last glimmer of hope for his survival extinguished.

He was one of my favourite historians. The void created by his passing away will be hard to fill. This should not be construed as a cliched statement issued on the death of almost every person of some reckoning. Mushirul Hasan was indeed a class apart as a historian, teacher, archivist and an intellectual rolled into one. He wrote extensively on themes pertaining to partition of India, communalism and the history of Islam in South Asia.

While at the University of Cambridge, I once inquired from Barbara Roe, the secretary and kingpin of the Centre of South Asian Studies, about someone other than great Chris Bayly who was as prolific as him, wondering if she would say Mushirul Hasan. But then Hasan was a student of Dr Anil Seal who had adversarial relationship with Chris. I thought Roe, being a big admirer of Chris Bayly, would utter someone else’s name. But she immediately said "Mushirul Hasan".

Hasan wore several hats. The fact that he found time for academics amazed many. He kept producing book after book despite the onerous responsibility of being the Vice Chancellor of Jamia Millia which was awfully demanding and then travelling too as he had a penchant for globe-trotting.

He was, undoubtedly, prolific and profound. Most importantly, his was the voice that represented North Indian Muslims in a very lucid manner in the light of the Nehruvian vision. Shahid Amin is spot on when he says, "he (Mushir ul Hasan) wrote widely and with great insight and total command of sources and texts on a jaw-dropping range of themes and topics, events and personalities". In him was a rare blend of ‘internationally reputed’ and widely acclaimed top-notch scholar and a great institution-builder. This made Mushir ul Hasan a distinct person vis-a-vis his peers and fellow academics.

His services as Vice Chancellor Jamia Millia Islamia, Delhi would remain etched in the memories of academics and luminaries for a long time. He was a worthy successor of another historian and scholar par excellence Muhammad Mujib. Stepping into the shoes of such a well-reputed historian was indeed daunting but Mushirul Hasan rose to the accession, picked up the gauntlet and now his name has virtually become synonymous with Jamia Millia.

Prior to becoming the Vice Chancellor, he also served as the director of Academy of Third World Studies in in Jamia and then as pro-Vice Chancellor from 1992-1996. In May 2010, Hasan was appointed the Director-General of the National Archives of India. He also held academic positions at Berlin, Paris, Cambridge and Oxford. He was bestowed with Padma Shri, one of the higher civilian awards in India, because of his meritorious services.

Son of Muhibul Hasan, a renowned medieval historian, Mushirul Hasan went on to do his master’s in history from Aligarh Muslim University in 1969. He proceeded to England in 1973 with the aim to do a PhD and enrolled in the University of Cambridge. He completed his degree in 1977. In his PhD thesis, he studied the connection between nationalism and communalism in northern India from the 1880s to the 1930s. Thematically, it was something akin to what Francis Robinson did in his monumental book Separatism among Indian Muslims: The Politics of the United provinces’ Muslims 1860-1923. Robinson’s study is considered path-breaking and rightfully so. But Mushirul Hasan’s scholarly endeavours were richer in sources that he used with dexterity. His command on Urdu, Hindi and Awadhi put him in a position of advantage. Then he had insider’s information about the politics and culture of Uttar Pradesh. More importantly, Hasan’s emphasis, as against the historical insight of the Cambridge School of Historians, was on nationalism, constructed and formulated the way Gandhi, Nehru and Maulana Azad envisaged it.

He projected and underscored in unequivocal terms, Islam and Muslims as committed constituents of Indian nationalism which was secular and plural in its character. Thus, he looked askance at the separatist agenda of the All India Muslim League and argued that such separatist tendency that Muslim League came to represent weakened not only Muslims but Islam as a civilizational force. Like other Indian-Muslim nationalists, he spurned the politics that called for a separate state for Muslims. Despite the peculiarity of Mushirul Hasan’s nationalist ideology, which may meet the disapproval of us as Pakistanis, his works have a lot for students of history to learn.

Also read: Making sense of history

During his last days, Mushirul Hasan was a dejected man. With the ascendancy of BJP under Narendra Modi and the likes of Amit Shah and Yogi Adityanath (Chief Minister of Uttar Pradesh) having found so much prominence in Indian politics, the ideology that Hasan advocated all his life so zealously, appeared to be unravelling before his eyes. Nehru was demonised with impunity and his vision lay in tatters, with voices like Hasan’s that represented pluralism and multicultural Indian ethos enveloped in utter helplessness.

Savarkar’s exclusionary ideology and not Nehru’s secular vision has come out as the defining feature of India, projected as the biggest democracy of the world. One wonder about the relevance and pertinence that scholars like Mushirul Hasan will hold when Hindutva is reigning supreme in India. One can only hope that better sense will prevail but from Modi and his cronies one may expect anything but.