The ongoing debate about restitution of cultural heritage has no final answer but it should all be saved and preserved with least damage

When the French President Emmanuel Macron was campaigning for his presidency in France, he called colonialism a crime against humanity. Later, on a visit to Burkina Faso as president, he announced temporary or definitive restitution of cultural African heritage to Africa.

He has been chiming in with a long-standing demand of countries or cultures from around the world that the artifacts and cultural assets that adorn museums of the more developed countries, particularly of the Europeans, actually belong to the rest of the world, especially their colonies, and must be returned.

This demand has not really been limited to countries of Asia and Africa. It also curries favour with countries that once were seats of civilization but then lost influence and power to be incorporated into empires that were also basically European. The Greeks have been a typical example whose architectural and artistic remains now adorn the museums and art galleries across the continent. This transfer of cultural assets started soon after their decline. The Romans transported large swathes to their capital Rome and other parts of the country to assert their claim as the leading empire of the world, not exclusively exercising political power but basing it on a wisdom derived from a solid and rich cultural heritage.

The return of Parthenon Marbles to Athens gathered further momentum when a commission formed for the purpose by the French president stated "as collections cannot be dissociated from the historic crime of colonisation, whether actually looted or not, there is just one appropriate course of action, restitution -- the return of works to their rightful owners". It however envisaged a process that was to commence swiftly, was wide-ranging but not time-limited.

All this has been further backed by an acrimonious debate about the various acquisitions made during the Nazi occupation, preceding and during the world war, of large parts of Europe. There have been demands that these acquisitions, largely stolen or taken into passion under duress, be returned to the countries or families that these belonged to, in particular reference of much of the art work that was pilfered or wrested away from the Jews.

It appears that the assertion of the director of the British Museum Neil MacGregor, who in 2006 had called repatriation is "yesterday’s question", is less convincing in today’s world which is more edgy about immigration, globalisation, sovereignty, history, race and historic injustices.

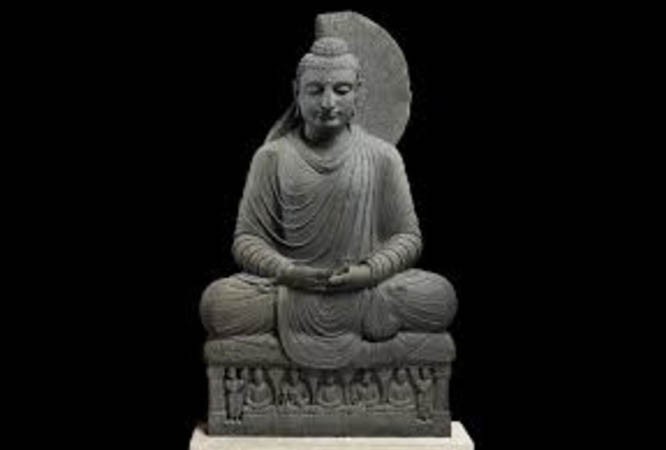

The Indian subcontinent has also been shaved off much of its fineries by the colonialists in the past three hundred years or so. It is probably very difficult to say what once belonged here is now in collections in the west because some has been documented, while not all is. These collections may be huge or small , in the possession of individuals or families, not visible to be identified for the purpose.

But it should not only be limited to the west. When Nadir Shah invaded Mughal India, the fortune that he amassed reflected in the restoration on a monumental scale of the various shrines in his empire. Ahmed Shah Durrani-Abdali’s loot was so much that he had the resources to found a new country called Afghanistan on the north western part of the subcontinent.

The question is a complicated one and is like unravelling history itself. The contentious point is the cut-off date, each established according to convenience. These days the villain is European imperialism but, in the past, we have seen generally two approaches -- one to destroy everything that belonged to the vanquished or to take back home cultural assets, either as trophies or to be eventually appropriated as their own. Gilgimash, Pharaohs, Cyrus, Alexander, Chengis Khan, Ummaiyads, Abbasids, Tamurids, Safavids, Mughals and Ottomans all did this without fail.

The question is if it all happens, the dream comes true and much of what has been taken away is returned, what will we do with it. The state of our collections and the museums needs a lot to be desired, not only because we are not that caring and sensitive about our heritage and the past but because there has been a paucity of resources and as a consequence of expertise. In societies straddled by poverty and backwardness, the entire effort however imperfect boils down to dealing with the basics of providing employment and raising the level of the people above the poverty line.

It is thought that the finer aspects, as these are labelled, can lie on the margins and wait while the more urgent and pressing matters of feeding mouths be dealt with. It has been argued that these artifacts/heritage items have been saved and properly documented in those erstwhile imperial societies and that their fate might have been different if these had stayed back home.

There are suggestions and options being considered like long-term partnership between the countries that hold the work and the place of its origins: that these be loaned to countries that the works belong to and of temporary transfers.

It does require much thinking and preparation and should not be rushed in just to make a political statement or flash it like a great achievement. After all, whatever is created here is the collective heritage of humanity and, though the landscape has been riven by various nationalisms, races, ethnicities and now gender, it is a common pool that should be saved and preserved with least damage, rather than further fuelling a debate about what is yours and what is mine.