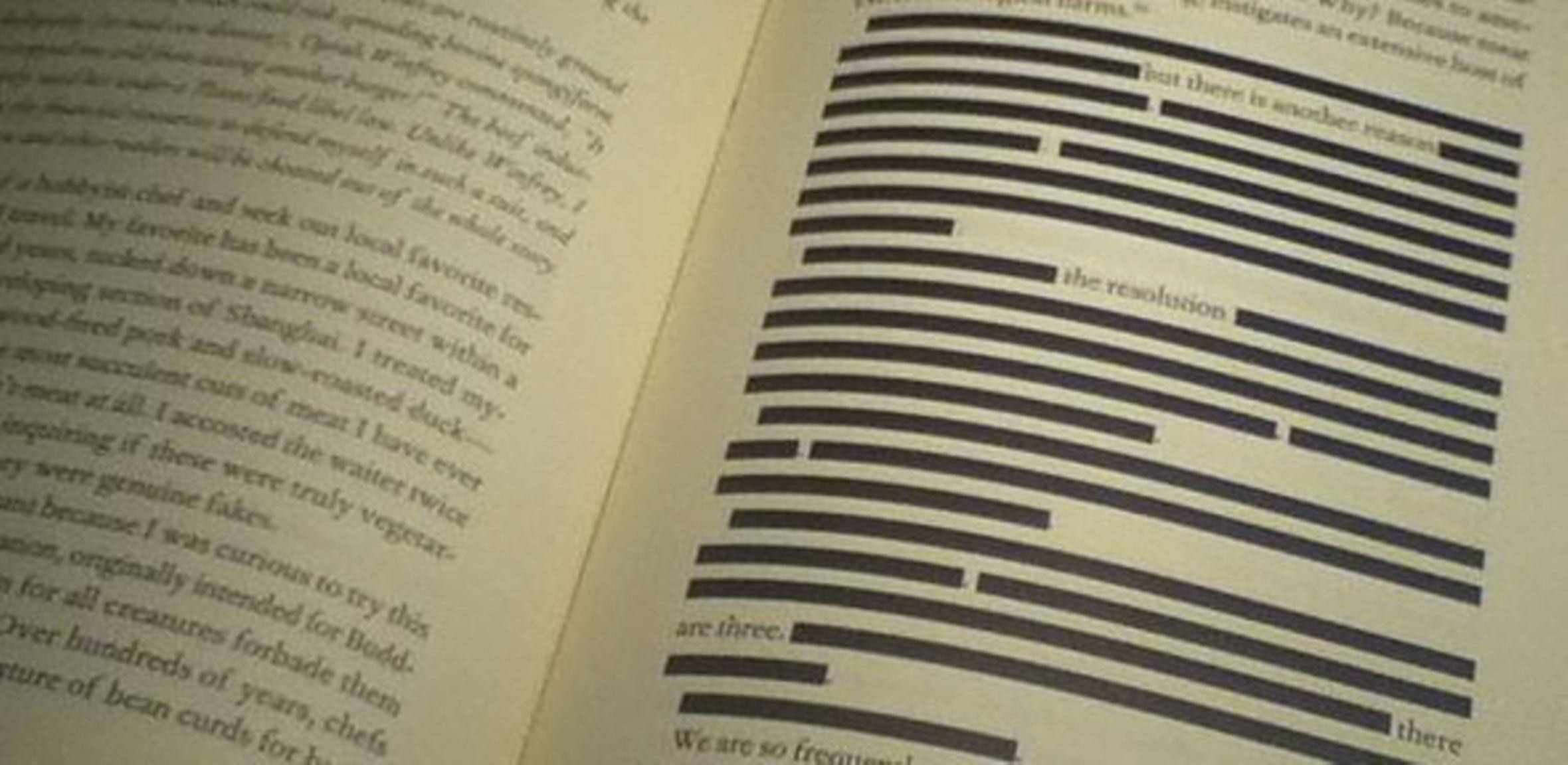

It’s a black or white, right or wrong, social order. While it’s in the realm of grey that you can question,challenge, create, complain, love, hate, be pluralistic, become controversial, and bring about a revolution

"The Ministry of Truth in present-day China has successfully persuaded a very large part of the Chinese public that the heroes of Tiananmen Square were actually villains bent on the destruction of the nation. This is the final victory of the censor: When people, even people who know they are routinely lied to, cease to be able to imagine what is really the case."

These are words of an author whose name is forbidden in this country as are his books. Online is another space, though. That’s where you can access them both. That’s where I found the above quote which seemed starkly relevant to the present times in the country I live in.

Talking of internet, the social networking site Facebook (FB) is now about 14 years old. Considering itself old enough to have a memory bank, FB keeps reminding the account holders of their memories, from six, five, or three, or even a year back. I recently read with shock an article I had written in 2012 that appeared in FB memories, wondering how it got published. A friend I met recently expressed similar horror about an article he wrote about a year ago that also popped up in FB memories. Slowly but surely, we are getting there.

A publisher of a recent Urdu novel, that breaks boundaries and is refreshing in so many ways, inboxed me: "let’s hope it doesn’t get read by the wrong people". Publishers not wanting people to read the book they’ve published might seem strange. But that’s the kind of world we inhabit these days, where publishers and editors are praised for their ‘courage’ to publish what they normally should.

I too sent an article by a ‘banned’ writer to a friend in his FB Inbox instead of posting it on my wall. Perhaps, it wasn’t secure enough. WhatsApp might’ve been better perhaps.

English language journalism was once considered safe in our part of the world. Some senior journalists considered only this as journalism and the rest as propaganda. It allowed a degree of freedom which was exercised with professionalism and responsibility. No one knew if it was an advantage or disadvantage that the masses could not read what was being published in the English language press. At least the policy makers could, the staffers consoled themselves. As for the censors, they were not really bothered. Till at least a few years ago.

The masses cannot be underestimated, especially in a democracy, especially in a country where even the coups are made in their name. They must be persuaded first -- about the significance and notions of Allah’s sovereignty, the fortress of Islam, ideology and national security. This is priority and is duly done. The fundamental rights that belong to them can come later. It is not too difficult to persuade them and bring them out in hordes when the national interest or religious honour is at stake. A mere mention of ‘blasphemous’ content, even if it’s in English, is enough.

The persuasion (mistakenly seen as social engineering by some) begins with textbooks. Encarta Encyclopedia considers offensive material as that which "may be considered immoral or obscene, heretical or blasphemous, seditious or treasonable, or injurious to the national security". We could mark ourselves safe on each account, perhaps even more, when it comes to textbooks.

A friend who was involved in developing a textbook for Intermediate English language was asked to introduce international festivals to students. She picked Nowruz (Iranian new year day that predates Islam) as one. She was told the festival is celebrated in a Shia country and might offend the sensibilities of the local Sunni population. I forgot to ask her what she replaced Nowruz with.

Special care is taken about history books. If you have managed history, you have done it all. The privileged children taking international exams cannot be an exception. So this year, the specified history book by Nigel Kelly for O level students was banned by the Punjab Curriculum and Textbook Board for containing ‘anti-Pakistan’ material. Ironic that some historian friends considered the book a lot more on the ‘pro’ side.

Also read: Monitoring in the digital age

Ours is a march towards unfreedom. There is a lot of noise, no doubt, but listen to it carefully and it is all of one kind. It is not just the work of the artist or creator or thinker or writer that is at risk. The artist, thinker, writer, dissident could himself disappear, striking fear among the rest.

It’s a black or white, right or wrong, social order. While it’s in the realm of grey that you can question, challenge, create, complain, love, hate, be pluralistic, become controversial, and bring about a revolution. Restrictions have a habit of multiplying, but does anyone care.

I read another interview by the same author, this time in a book: "When you start restricting the speech of one, you end up by restricting the speech of all, and in the end, nobody can say what they think; and if you live in a country where nobody can say what they think, that is a definition of insanity."