Let Her Fly is a treatise on progressive parenting and an inspirational tale of a man’s fight to defeat misogyny - both within and without

For the past six years, Malala Yousafzai has been the one constant source of positivity for Pakistan. That she has only been able to spend four days of these six years in the country is a sufficient explainer for why she had to leave in the first place, and perhaps underlines a symptom gorier than the Taliban bullet that nearly killed her.

Granted Pakistan paints an ever so slightly rosier picture on the counterterror front than it did on October 9, 2012. However, recent events remain a resounding reminder that the battle against religious extremism is far from won.

Perhaps it’s in the stars for Malala to sound the death knell for the Taliban, and those that similarly espouse a radical brand of the religion, upon her formal homecoming.

Ziauddin Yousafzai certainly believes so. For him, his daughter’s birth signified a morning star - the brightest in the sky - that first illuminated his family, and now is destined to shine across the world; a journey he encapsulates in his memoir.

Even so, Ziauddin Yousafzai’s Let Her Fly: A Father’s Journey is not just a story about the girl who lived. It is as much about becoming Malala as it is about the circumstances that make a Malala - a global force to reckon with in the realm of girls’ education and rights, who was a whisker away from death.

"Was Malala’s passion for school due to nature or nurture? I think both. You can say that Malala was a perfect seed in the perfect soil, a magical seed in the most conducive soil for its nourishment."

Ziauddin’s story begins a few decades before Malala’s birth, in Barkana his village in the Shangla district of northern Pakistan. He was born in a conservative Pakhtun family, with his father - a quintessential patriarch - being a village imam.

From an early age, Ziauddin noted the ‘feudal jealousies’ that had established the patriarchal order in his family and neighbourhood, perpetuating gender inequality and serving societal injustice to every woman born therein.

The seeds to challenge Islamist orthodoxy were also sowed early on, as an encounter with a saint tasked with curing his stammering reveals. He felt from an early age that the Islamic scriptures were conveniently misinterpreted by men to subjugate women.

It is evident that such thought could not have taken root in his mind at such a young age without the influence of other women. Here he credits all three of his "mothers", to whom he dedicated the first collection of his Pashto poetry in 2000: his birth mother, his father’s second wife and "a kind woman" who treated him like a son when he boarded at her house during his college years.

"I suppose you could say as a woman my mother gave me something beautiful. She was not educated herself, but she could see the value of education."

Having seen a female cousin being brutalised after being married off at the age of 14, left a further mark in Ziauddin’s head as he felt a growing need to address the societal gender imbalance at a time when he couldn’t put any ideologies or labels on what it was that he clearly wanted to strive for.

"[E]ven as a ten-year-old, I remember I was beginning to really enjoy serving women in the village. I was too young at that point for it to have been a kind of protest, but I remember the pleasure I felt in helping them."

Naturally when Malala was born as the eldest of his three children - following a stillborn first child - Ziauddin wanted to raise her differently to how other women in his family had grown up. However, he would soon realise that despite a generation having gone by, his quest would still remain a bubble surrounded by aggressive conservatism.

By 2007, the Swat valley was the hub of a full-blown Taliban invasion, and as they slashed a ban on girls’ education, Ziauddin’s challenge became that much more ominous. The storyline that followed for the family is now known the world over.

Again, more than the threat posed by a Taliban insurgency, Let Her Fly is a unique lesson in raising three kids, when one of them is the youngest ever Nobel Laureate.

For instance, dealing with his son telling a close friend that "my father is not taking care of me like he is taking care of Malala", or fighting off the occasional patriarchal urge to replicate the authoritativeness that the men in his family had exhibited.

"Where had the liberal Ziauddin gone? The father who saw the error of his ways back in Pakistan and believed in equality and freedom and in encouraging his sons to express themselves?"

There is brutal honesty brimming over every page of Let Her Fly whether it comes to acknowledging the internal struggles involved in raising his kids, or looking to pin the blame on himself when any of them was in harm’s way - whether it was Malala in front of the Taliban gun or Khushal who was in Abbottabad at the time of the Osama bin Laden raid.

It wouldn’t be wrong to dub Let Her Fly as perhaps the first guidebook for fathers - or men in general - who aspire, in our neck of the woods, to be feminists - a label that Ziauddin only heard after moving to the UK after living it for more than forty years.

His message to the fellow menfolk is simple: not to clip young women’s wings and let them write their own stories.

Here he acknowledges the massive role that his wife, Toor Pekai, has played, not just as a mother and a wife, but as a companion who helped him fight the battles within and provide clarity of thought.

Let Her Fly is a treatise on progressive parenting, an ode to a world-conquering daughter, a reminder of the challenges for a still volatile country, and most of all an inspirational tale of a man’s fight to defeat misogyny - both within and without.

Ziauddin urges all the men out there not upholding regressive values on gender to speak up and loudly reject patriarchy. For, it is his embracing of unlearning that gave this world its most prominent fighter for girls’ right to learn.

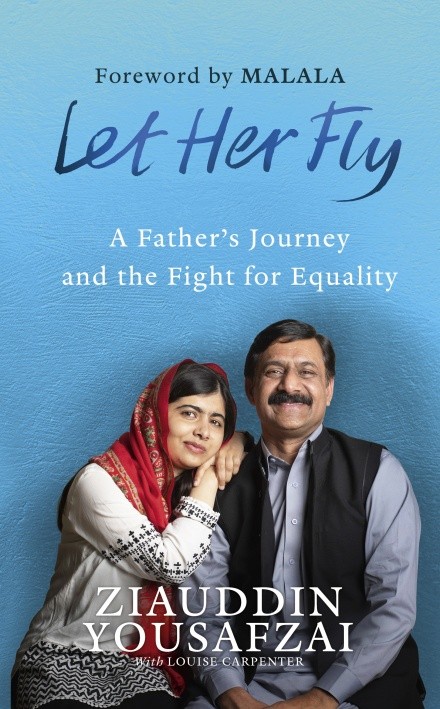

Book: Let her Fly: A Father’s Journey and the Fight for Equality

Author:Ziauddin Yousafzai, Louise Carpenter

Publisher: Random House

Pages: 240

Price: 1,395