Some scholars believe that in prehistoric times most of the societies on earth were matriarchal in nature. It is a claim which is difficult to verify. However, the prevalence during unrecorded history of images of a Mother Goddess, who symbolised fertility, does indicate that women may have once played a major role. Perhaps matrifocal will be a better word in the context. Leonard Shlain in his interesting but controversial book, The Alphabet versus the Goddess, posits the idea that it was the invention of writing which led to the rise of patriarchy and women lost most of their privileges.

Whatever the situation five or six thousand years ago, whether a continuation of an old order or a radical change, one thing alone is certain. Almost everywhere patriarchy appears to be in the ascendance. Nothing in the ensuing centuries altered, particularly as far as the middle class was concerned. Women were muzzled or forced to lead secluded lives. No wonder, therefore, that Urdu Literature had not a single woman writer or poet of note for centuries. It was only during the 20th century that women began to make their presence felt. Conservative elements still find the rather limited freedom that women enjoy quite distasteful. Luckily they can’t enforce their writ. As a result, we can now point to a number of excellent writers of fiction or poetry who are women. Also a few critics among them. A step towards equality or an end to what could be seen as a gender-based apartheid.

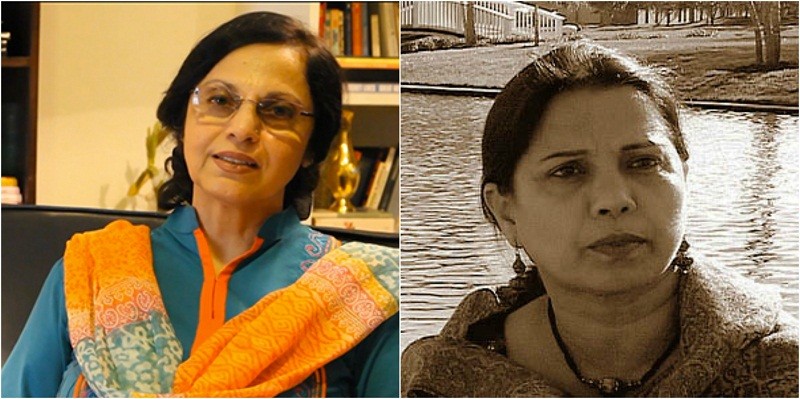

Yasmeen Hameed is a poet to be reckoned with. So far she has published five collections of poetry which carry poems as well as ghazals and has maintained throughout a level of notable dexterity. She has translated a substantial number of Urdu poems into English, enough of them to make up an anthology. It suggests that she is equally at home in English. As an educationist, she is not without distinction. All in all, her creative reach is indisputably considerable.

Her latest book Hum do zamanon mein paida hue is a selection. As her collected poetry appeared in one volume in 2007 and she has published only one more book of verses since then, the selection seems somewhat unnecessary. But poets tend to be whimsical. The poems and ghazals have been picked by Razi Mujtaba, a well-known poet himself. As the selection is fairly generous, nearly 400 pages in all, it is unlikely that Razi would have missed anything worthwhile.

In her preface, which first appeared in her fifth collection, back in 2012, and has been reproduced here, she says that the number of those who read poetry in Pakistan has declined drastically over the years. Very rightly, she squarely blames our askewed educational system for this downturn. As no one is seriously interested in setting things right, the situation can only worsen in the future.

What does the title "we were born in two ages" imply? No answer has been provided. It does make sense if looked at from a different angle. Although we live in modern times and obsessively lap up the amenities now available, a great deal of our thinking is still rooted in the middle ages. This dichotomy causes a split in our consciousness. It is a situation not explicitly commented upon in her poetry but can be felt at times as a strong undertow. In any case, her poetry is often private and reclusive and focuses indirectly, without any declamatory reactions, on the unjust world we have been forced to inherit. Our choice of exercising a free will is largely hampered and we can be thankful for small mercies only.

It is not to say that she is unaware of or indifferent to the unfairness around her. One has only to read her nazm (poem), ‘Kaun hay merey shehr kay waali’, to see this. There are oblique references to injustice scattered in her work. Those poems which are formalistic in appearance, for example, ‘Baat say buhut pehlay’ or ‘Aik do teen char’, are generally more successful in expressing a mood. Nevertheless, the most powerful poem here, ‘Album’ packs a powerful punch in very few words. Her ghazals, because of their prescriptive formalism, have an edge over her nazms. One of the best begins with the line, ‘Rait hay, raat hai, sitara hay’. In it a word from the first couplet descends into the second, to add to its suggestiveness, and from the second couplet, another word is ensconced in the third and so on. The total effect is one of a striking close-knit design. The cumulative impression that Yasmeen’s poetry conveys is that of a sensitive and pensive soul, witness to an era winding down. She can save very little from the wreckage, perhaps only pulsations from shattered memories. None of us have done any better.

On the other hand, Ishrat Afreen’s poetry, collected in Zard patton ka bun, is unreservedly feminine but not feminist. A distinction which should not be lost sight of. Her vision or outlook owes very little to any particularly theorising. The rather plain and plaintive tone of her ghazals and nazms stays a touch above nostalgic outpouring, redolent of discontent.

In her poetry what matter most are small places, whether villages or dusty, remote towns, small thing of life, whether tragic or blessed or a mere repetition of ordinariness, people, especially women, who live on in a sort of dazed wonder, neglected and neglectful. The sympathy with which the daily ordeals of women or girls is observed has nothing contrived about it. In spite of a not quite explicable sadness, Ishrat’s self-contained world is awash with colours and voices and recurring seasons. There is a strident note of protest here and there as if she were regressing to the dated pastures of progressive poets. On the whole, she is very much herself and her poetry live enough to face the world on its own terms.

Another interesting aspect of her poetry is its homely diction which does not pay court to a Persianised register of the language. Even her ghazals are unusually free of the played out verbiage associated with the genre. These disconnections, carefully chosen or germane to her nature, are refreshing and make her poetry appear a little different from what we are accustomed to read.

Will she continue to write in the same vein in future? The idea is not reassuring. Only she herself can come up with an answer. It will be a pity if she does not move on to a new plane of verbal excellence.

Yasmeen Hameed’s book has been published by Academy Bazyaft, Karachi, and Ishrat Afreen’s by Sang-e-Meel, Lahore