Anam Zakaria’s new book is an original and significant addition to the contemporary history on Azad Kashmir

Anam Zakaria made her mark as a historian using interviews as her major research method in her pioneering book The Footprints of Partition (2015). These were narratives from the partition of India in 1947 which has left indelible marks on Pakistanis and Indians of four generations. While this was a significant and worthwhile addition to the archive of the oral history of South Asia, it was not the only work of its kind because there were many other authors who had captured the trauma of the partition using interviews.

The book under review, however, is definitely an original and significant addition to such kind of contemporary history because there is no such history of Pakistan-administered Kashmir (henceforth Azad Kashmir as it is popularly known in Pakistan) to my knowledge. Incidentally, while the author could not get the opportunity to interview people in the Indian-administered Kashmir, she has referred to such sources as are available to her which presents a fairly good picture of the other side also.

The book has three parts and ten chapters and all references are in the footnotes which makes it easy to trace outsources used by the author. The first part is about the history of the Kashmir conflict which has led to three wars between India and Pakistan and an ongoing insurgency and covert guerrilla warfare which makes it impossible for South Asia to develop and find peace. Since the interviewing technique allows an author to take the subaltern point of view into consideration, it enables one to understand what ordinary people suffered in these conflicts. In chapter 1 and 2, we learn that during the 1947 war, the ordinary Kashmiri Muslims were so afraid of the Pashtun tribesmen that the women would go and hide in the jungle when they heard they were approaching. An old woman, the mother of her interlocutor, tells Zakaria that: ‘we had heard that they would cut off women’s ears, slice their necks, taking away all their jewellery’ (p. 20).

The book is full of accounts which help us deconstruct the narrative of the Pakistani state that these people came to fight Indians only out of Islamic fervour. There are other harrowing incidents, for example, one narrated by a woman who converted to Islam from Sikhism just to save her life. She told the author that her aunt (bua) was trying to run away from an attack by the same when her two children were separated from her. Her baby was in her arms but it was crying so much that the other Sikhs felt their hiding place would be betrayed by this noise. Said the woman: ‘to save everyone my bua sacrificed the baby…she threw her baby into the river’ (p. 34). What happened to the unfortunate mother’s mental equilibrium after this trauma is not recorded. There are records of people becoming too depressed to speak or function normally after such events.

As the Indian-administered Kashmir became increasingly violent especially after the 1987 ‘rigged’ elections which the Kashmiris protested against, the Indian security forces forced young Kashmiris to take up arms against the Indian occupation of the Vale of Kashmir. Chapter 3, which features the interview of a former militant from the Hurriyat Conference, gives us an insight into this turbulent time. The Mujahideen commander -- as he calls himself -- gives the details of the inhuman humiliation and violence which boys like himself experienced before they took up arms. These circumstances also forced out families which did not join the militants but were always picked up for interrogation on the suspicion that they had. The author interviews one such family and the details of torture, including electrocution, at the hands of Indian security agencies which they narrate, are harrowing.

Indian atrocities are not confined to those who live in the Indian-administered areas of the former state. They are also visible in the areas of the Neelum valley and some forward locations in Kotli which the author visits. In the former location, the author visits Athmuqam where she witnesses first hand the devastation brought about by heavy mortar and gun firing by the Indian army.

The women were reduced to living a life reminiscent of the trench warfare during World War 1 (1914-1918) with the fear of a painful death always hanging over their heads. One of them complained that she had to leave her infant child howling in terror because the hail of bullets and shrapnel was so intense that she could not pick him up. This firing continued throughout the 1990s as it was meant to deter militants crossing over from Pakistan to carry out a guerrilla war in the Indian-administered areas. But these women were unusually enterprising since they protested against the crossing over of militants to the army itself and did achieve some positive results. In Kotli, however, where the author interviewed a man whose wife was killed in such firing, nobody had the courage to protest (see pp. 271-274).

In part 2 the author interviews senior military officers and refers to documents to record the official narrative. As usual in such cases, it is about the land not about the people despite the rhetorical use of their ‘right of self-determination’. The indigenous movement for freedom from India was usurped by fighters from the Pakistani Punjab and other areas. These militant organizations -- those led by Hafiz Saeed and Masood Azhar for the most part -- injected religious extremism in the struggle which squeezed out the indigenous Kashmiris who were more eclectic and secular, to begin with. Moreover, those who wanted freedom from India but did not want to join Pakistan were also squeezed out.

It is the crossing over or attacks of Pakistan-backed groups which brings about both firing and the violent retaliation of the Indian security forces against Kashmiri Muslims nowadays. That is why some interviewees, especially women, wanted everyone to just give up on the guerrilla warfare which, in their view, had only led to the untimely deaths of their loved ones and unbearable pain for those who survived.

Chapter 9 is about a scarcely known subject in Pakistan -- the nationalist Kashmiris in Pakistan-administered areas who want independence from both Pakistan and India. They object to the domination of Pakistan on their decision-making process, the lack of development in their area and the non-payment of the royalty from the Mangla Dam which supplies a lot of power to Pakistan. Despite the anger and fervour of the interviewees, the author concludes that the real brunt of the state’s ugly face is seen only by those who are governed by India.

The book has debunked official narratives of both the states of Pakistan and India. It is centred entirely on the people and their sufferings, views and feelings. It is a genuinely subaltern oral history of a conflict which is still going on and which needs a peaceful solution. The overall feeling as expressed in their interviews is that they would keep struggling for their rights and freedom but no longer through militant means.

The author has not claimed that this is a scholarly work in the conventional sense of the term but she has used relevant sources judiciously and competently as one does in scholarly writing. Perhaps, if it were one in the conventional sense, it would have had a more detailed review of the literature and possibly lean upon some theory to frame its narrative. These, however, are not necessary to search for the truth and provide insights which have eluded scholars so far. If several Indian, Western and other sources had been cited the book would have met with the approval of pedants, but nothing substantial would have been gained. Such original insights which the book provides are the product of a very brave attempt at doing research in a dangerous region with the risk of being suspected by militants or the security forces for being a persona non grata. The author should be commended for her hard work, acumen and courage. Her husband, Haroon Khalid, whom she thanks generously, also deserves the readers’ gratitude for having supported her in such a perilous task as this research project. Very few husbands in Pakistan do as much for their wives.

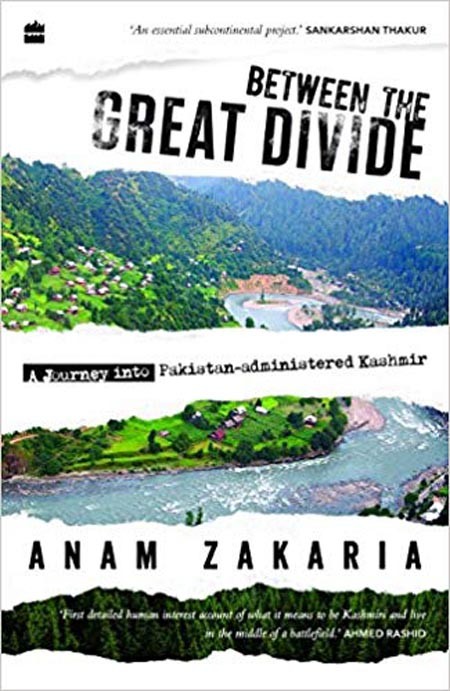

Between the Great Divide

Author: Anam Zakaria

Publisher: HarperCollins India, 2018

Pages: 282

Price: Rs1,395