When Kanhaiya Lal turned his attention to history

Kanhaiya Lal was a prolific writer, writing being a principal source of personal gratification. In his free time, he used to read extensively. At the very outset, he wrote a few books on Mathematics and Engineering, some of which were in English. Kanhaiya Lal was cognisant of moral decay that had crept into the social fiber of the indigenous people, which prompted him to write a book on morals. The book which was in versified form won him accolade as well as appreciation from the rulers (British).

This reformatory streak was an interesting aspect of his personality which kept forcing Lal to write books, publish them and to distribute them free among those who could read. Only a reformer could do such a commendable thing. One can surmise that despite his unequivocal loyalty for the British, he held indigenous values very dear and earnestly wanted them to be revived. That explains why he chose Persian as a vehicle for transmitting his thoughts to his compatriots. More so, he employed poetry as a mean to instruct local literati.

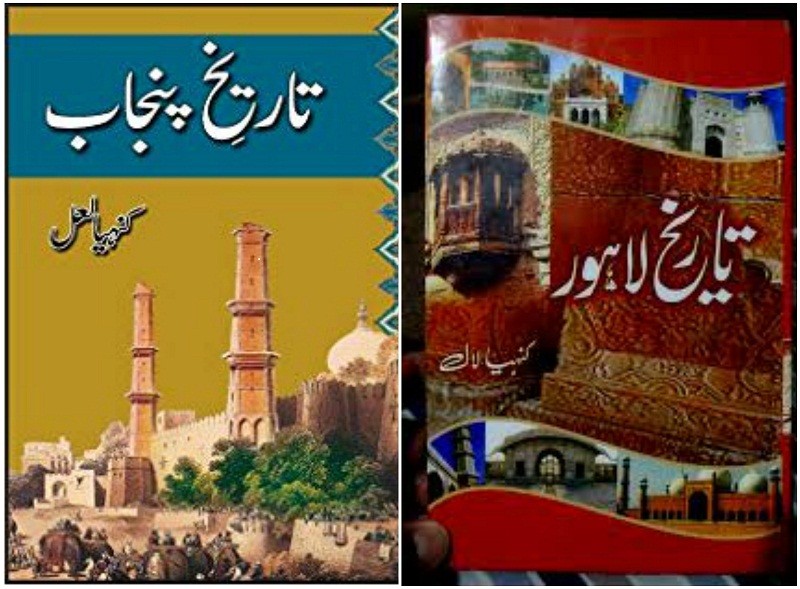

He saw political decline as an outcome of the moral depravity of the Indians. Therefore in order to re-invent themselves, they needed to revive and rinse their value system. That was the principal theme of his poetic works, which he produced before turning to history by writing Tarikh-i Punjab and Tarikh-i Lahore.

His first book comprising Persian poems was titled Gulzar-i Hindi and second one was called Bandagi Nama, which too was a book of poetry. Yadgar-i Hindi was his third book of Persian poetry, followed by two books in Urdu, Manajat-i-Hindi and Akhlaq-i-Hindi. The form and content of these books -- poetry and morality -- were quite similar to the previous narratives.

After having composed these works of poetry, Kanhaiya Lal turned his attention to history. That branch of knowledge was vital for him as an instrument for breathing a new life into the collectivity of people who were subdued and suppressed. History has that power to connect the people living in the present with their past; thus it ensures continuity. It is important to underline here that the severing of connectivity between the past and the present leads to socio-political decay. Hence, history as a discipline (or a branch of knowledge) is essential in that bid of re-connecting with the past. That happens when people start writing their own history.

My admiration for Kanhaiya Lal stems from the fact that he, despite being an engineer, diverted his energies towards writing history. Thus Zafar Nama (which subsequently became popular by another title, Ranjeet Nama) was his first book with history as its theme and purpose. That book was in Persian and its form was poetic. Soon afterwards, he sat down to write his first book in Urdu prose, Tarikh-i-Punjab; probably one of the first books of regional history written in Urdu.

As a book of history, Tarikh-i-Punjab is chronological with a linear trajectory, expansion of Sikh state being its central theme. The major part of the book can also be classified as a catalogue of wars and battles waged by the Sikhs. However, he also mentions though briefly about the Sikh gurus and the ascendancy of their twelve misls (confederacies), which had emerged in the wake of Mughal downfall. The book deals with the political history of the era which has been of tremendous significance for our young historians. A profound sense of history can only be inculcated through an incisive reading of downfall. In Tarikh-i-Punjab, the advent of Ranjit Singh as the sovereign of the Punjab was thoroughly mapped in accessible and lucid style.

Read also: The historian of Lahore-I

Kanhaiya Lal has refrained from ornate and Persianised language. That allows the readers of this day and age to relish that book without encountering any idiomatic barrier(s). In his assessment of the rise of Sikhs as a political force and their subsequent downfall, Lal seems quite disinterested, objective and balanced. Having said that, he has abstained to furnish any critical view of the British period, which was the concluding section of the book. It is undoubtedly an essential read for those interested in Punjab’s history when that region was going through the period of transition.

The best book of Kanhaiya Lal was Tarikh-i-Lahore. It covers all aspect of Lahore’s history, geography and its social life. Despite 130 years having gone by, it still is one of best expositions on Lahore. The cultural aspect is the most striking of all the features of this book. Interestingly, he has used his professional insight in his writing of Lahore’s history. The dilapidated state of ancient and medieval buildings triggered his interest in architectural history of the city, which was the first experiment of its kind. It is with an eye of an architectural expert that he describes the thirteen gates of Lahore. The description though brief is still quite comprehensive.

He informs us about the newly-established institutions, mosques, shiwalas, mohallas, gardens, mausoleums, havelis and graveyards. He also provides a comprehensive list of professional and artisanal classes, important personalities and renowned families. The newly-built buildings like railway station, building of Government College Lahore, Mayo School of Arts along with several other such architectural structures have been described with precision. The format of the book indicates that the author was influenced by the way the district gazetteers were put together by the district administration during the British rule.

Another aspect worth our attention is the cultural aspect of Tarikh-i-Lahore. Given the time period when it was written, it is quite a unique feature of the book. One may also conclude that Kanhaiya Lal was the first cultural historian of the Punjab. Tarikh-i-Punjab is a necessary read but Tarikh-i-Lahore is a must read for the young students of history and culture.

(Concluded)